The Northernmost Station: Weather Observations in Alaska in 1926

- By AMS Staff

- Sep 9, 2021

Point Barrow Refuge Station, courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, AK,15-BARR,7-3

In the fall of 1926, the U.S. Weather Bureau announced that radio weather reports were beginning to come in from the northernmost station in the United States: Point Barrow (now Nuvuk), Alaska. But few people would have guessed that the observer at this farthest north weather station was a young woman. Mrs. Beverly A. Morgan and her husband - the Army Signal Corps radio operator - were two of only a few white inhabitants of the town, which was the coldest and most inaccessible station at that time: 450 miles north of other radio weather outposts.

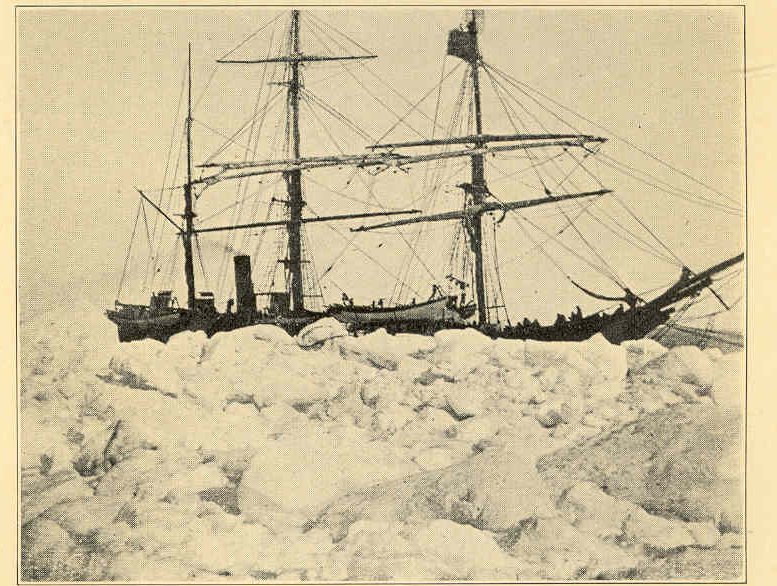

For Mrs. Morgan and her husband, there were only two ways to communicate with the outside world. One was their radio, and the other was a steamer ship that came once and sometimes twice a year. Occasionally though, even this icebreaker ship was unable to access the post for months after its scheduled arrival. Shortages of food and other supplies often caused serious handicaps at the station, and required the staff to ration their food. The average temperature was 19° (F) below zero during the coldest winter months, and could reach as low as 55° below zero.

The Steamer Bowhead gets stuck in ground ice at Point Barrow, Alaska

Despite these hardships, Mrs. Morgan pledged herself to make routine weather observations twice a day regardless of weather, storms, sickness or other conditions. Many of the instruments required considerable mechanical attention and Mrs. Morgan performed these duties in addition to her work as an observer. The arduous process of observing and tool maintenance was seen as having great importance to cold wave forecasting in the United States, and a new way to predict the approach of cold periods and winter storms in the continental United States.

Today, Mrs. Morgan’s work as an observer has become part of a long history of weather data from the Point Barrow station. This extended observational record shows that ice breaking ships would now have few problems resupplying the station because the ice has retreated from the shoreline and water temperatures have become too warm for ice to form in the fall due to climate change. Sea ice now forms almost a month later than it has in the past, and the permafrost thaws, so it is native hunters and residents that must be wary of having food supplies cut off. Hunting used to take place on the autumn sea ice that formed before the winter darkness set in, but that is nearly impossible in today’s conditions. Thawing permafrost can also threaten roads and increased flooding potential for communities in and around Point Barrow.

But as Mrs. Morgan and the native inhabitants of Point Barrow doubtless knew, one of the best responses to changing climate is more weather observations. It is often a struggle for scientific organizations to unite existing indigenous knowledge with academic data collection and research, but weather is a place where this collaboration is incredibly important. One modern project that Mrs. Morgan would no doubt have contributed to, is the SIKU web platform and app, which is built by and for native communities to provide services around ice safety, language preservation, and weather information. Through tools such as these and ongoing weather research collaborations between indigenous communities and research scientists in the Arctic, a long tradition of weather observation grows stronger and more inclusive.