Observations in the Great Unknown

- By AMS Staff

- Jan 28, 2022

Weather observations became a major business in the 19th century, as countries recognized the importance of this science and competed to gain economic and strategic advantages. The Austrians created the first national meteorological service in the world in 1851. England was a close second, as Admiral Robert FitzRoy founded the United Kingdom Meteorological Office in 1854. Other countries followed: India in 1875, Finland in 1881, and the United States Weather Bureau in 1890.

But most of these countries were not looking to maintain weather networks only within their own borders. They also sought information about climate in their colonies. One of the explorers that supported Spanish colonialism in Africa was the Basque adventurer Manuel Iradier. His weather observations, diaries, and ethnographic and botanical notes formed an important record for understanding conditions in the Spanish colony of Equatorial Guinea. But it was eventually revealed that he wasn’t quite as responsible for the weather observations as he led people to believe.

But most of these countries were not looking to maintain weather networks only within their own borders. They also sought information about climate in their colonies. One of the explorers that supported Spanish colonialism in Africa was the Basque adventurer Manuel Iradier. His weather observations, diaries, and ethnographic and botanical notes formed an important record for understanding conditions in the Spanish colony of Equatorial Guinea. But it was eventually revealed that he wasn’t quite as responsible for the weather observations as he led people to believe.

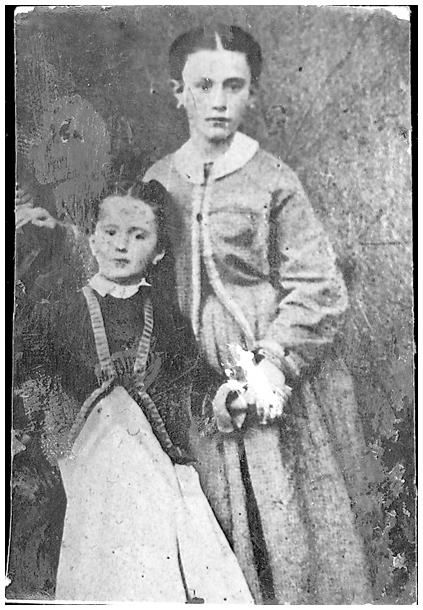

Iradier was eager to explore Africa. He founded a young explorers club as a teenager, and led expeditions around Northern Spain as practice for exploring Africa. Finally in December 1874, at the age of 20, he gathered enough personal and family financing to travel to Equatorial Guinea. Critically for his scientific observations, Iradier did not embark on his journey alone. One month prior to his departure, Iradier had married Isabel Urquiola, the daughter of the local baker. Refusing to watch her new husband leave without her, Isabel and her younger sister Juliana (who was 18), set sail with him.

As they were not part of an officially financed expedition, the three traveled on a mail steamer to the Canary Islands, where they stayed for a few months to acclimate and test their scientific instruments. At this time, the Canary Islands was a busy hub of immigration, trade, and cultural exchange, as populations shuttled between a war-torn, poverty-stricken Spain, the newly independent Americas, bustling Caribbean islands, and the lure of Africa. It must have been unimaginably different for Isabel and her sister, who had never before left their home in the Basque region of Spain.

The Iradier-Urquiola party set out for Africa on 25 April, 1875. Sailing on another mail steamer, it took almost a month to reach the island of Fernando Poo (now Bioko). This was the main outpost of Spanish activity in the area at the time, and the governor of the island tried to prevent them from traveling further because of the lack of infrastructure and services in the rest of the area. Iradier refused to be persuaded, however, and he and the ladies continued south to reach the tiny Little Elobey Island, just off the coast of Equatorial Guinea. This became the base of operations, and 11 days after landing, they were taking the first weather observations.

In the book he later published about his travels, Iradier included over 100 pages of meteorological tables and weather discussions. Measurements were taken at least four times a day and included precipitation, wind, temperature, and relative humidity. Iradier built some of the instruments himself, including the rain gauge and anemometer. But throughout much of his time in Equatorial Guinea, Iradier was exploring the continent of Africa, collecting anthropological and botanical data. Instead, it was the Urquiola sisters who took most of these precise observations, recording rainfall at the start and stop of storms, and maintaining a strict schedule for all observations. Their efforts continued through Isabel’s pregnancy and frequent illnesses suffered by both sisters, but there is no mention of their contributions in Iradier’s book. Isabel’s involvement was only brought to light in 1886, when he briefly thanked her during a lecture that he gave to the Royal Geographic Society of Spain.

In the book he later published about his travels, Iradier included over 100 pages of meteorological tables and weather discussions. Measurements were taken at least four times a day and included precipitation, wind, temperature, and relative humidity. Iradier built some of the instruments himself, including the rain gauge and anemometer. But throughout much of his time in Equatorial Guinea, Iradier was exploring the continent of Africa, collecting anthropological and botanical data. Instead, it was the Urquiola sisters who took most of these precise observations, recording rainfall at the start and stop of storms, and maintaining a strict schedule for all observations. Their efforts continued through Isabel’s pregnancy and frequent illnesses suffered by both sisters, but there is no mention of their contributions in Iradier’s book. Isabel’s involvement was only brought to light in 1886, when he briefly thanked her during a lecture that he gave to the Royal Geographic Society of Spain.