Making WAVES: Women Meteorologists in World War II

- By J.M. Lewis

- Mar 9, 2021

Lois Coots was a premed student at Marietta College (Ohio) who had obtained a pilot's license

before she accepted a full scholarship to study meteorology at NYU. She was the only woman in a

class of 200 students who began the meteorology program in fall 1942.

Out of the nearly 6000 U.S. military officers who were trained to be weather forecasters during World War II, there were approximately 100 women. They were recruited into the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) by the U.S. Navy and underwent training alongside the men in their forecasting cadet program.

As World War II progressed, a shortage of technical officers left the U.S. increasingly vulnerable. In an effort to shore up defenses, what was then the U.S. Weather Bureau, the U.S. Air Force, and the U.S. Navy began to recruit women hydrologists, mathematicians, and meteorologists. In response to the need for reserve officers, a recruiting drive for WAVES with strong technical backgrounds was started. Media announcements on the radio and in newspapers were the rule. The Chicago Tribune of 23 February 1943 had a front page column devoted to this recruitment. Quoting from this article, "an arch [was constructed] over LaSalle Street in front of the Board of Trade building yesterday marking the opening of a 45-day recruiting drive for the WAVES . . . and the SPARS, women's reserve of the coast guard [Semper Paratus(L), Always Ready].

WAVES Officer Training Program

To be accepted into officer candidate school, the women were required to pass both a physical and intelligence exam. The written exam had a good deal of math and science on it, especially mechanics. Upon satisfactory completion of these exams, the women were sent to Smith College (Northhampton, Massachusetts) or Mount Holyoke College (South Hadley, Massachusetts) as "apprentice seamen" for one month's basic training. As recalled by one of the candidates, Eleanor Longbrake:

This was essentially boot camp...Not that we were given the rough treatment many army recruits received in boot camp, but we were quartered six in each dormitory room built for two with all bathroom facilities similarly limited . . . quarters inspected while at attention, marched in the summer sun and if someone fainted (usually while standing at attention for extended periods), she was required to stand at attention in sick bay.

Following the one month's training as seamen, the officer candidates entered “midshipmen" school at either Smith or Mount Holyoke. This second phase of training also lasted one month. At midshipmen's school, the women had classes and exams on USN organization, military law and regulations, navy ships and aircraft, and communication and correspondence. At the end of the two-month program, the women were commissioned as ensigns.

While at officers candidate school, recruiters discussed the various career options with the women. Since aerological engineering (meteorology) was an area that needed reserve officers in 1943, the recruiters were quick to offer this option. Those who entered “aerological engineering” were sent to either UCLA, MIT, or the University of Chicago. From archival information, we know that 63 WAVES received meteorological training at MIT. The number trained at UCLA cannot be determined precisely, but based on the recollections of the six WAVES who were contacted, the estimate is 20. Twenty-one WAVES were trained at U of C. Thus, the total number of WAVES who were trained as forecasters is approximately 100.

The Training Program

The cadet program was under the jurisdiction of the University Meteorological Committee (UMC), headed by Carl Rossby. This organization came into existence in late 1942 after the U.S. Air Force's efforts to recruit meteorologists began to lag far behind projected needs. The UMC was composed of two representatives of each of the five academic institutions (U of C, UCLA, CIT, MIT, and NYU) and the U.S. Air Force Training Center at Grand Rapids. Additionally, the U.S. Weather Bureau, U.S. Air Force, and U.S. Navy had representatives on this committee. The cadet program was rigorous and Rossby had vociferously argued for a 9-month program instead of the 7-month program proposed by the U.S. Air Force Directorate (Walters 1952, p. 79). In its final form, there were three 11-week terms, with a week's recess between each term. Counting an initial week for orientation and military drill, the cadet program lasted exactly nine months.

Cadet Program at the University of Chicago

The WAVES forecasters on the University of Chicago campus (quadrangles) in September 1943. Hometowns are given in parentheses following the names. Front row (left to right): Mary McCann (St. Louis, Missouri), Margaret Donovan (Los Angeles, California), Eleanor Longbrake (Waterville, Ohio), Alwyn Evans (Weiser, Idaho), Maud Greenwood (Hackensack, New Jersey), Dolly Gordon (Louisville, Kentucky), Mary Lou White (Evanston, Illinois), Kathleen Lancaster (St. Louis, Missouri). Back row (left to right): Alice Sanders (Los Angeles, Californa), Dorothy Bradbury (Roberts, Illinois), Catherine Bradley (Stubenville, Ohio), Bernadine McClincy (Spokane, Washington), Gladys Neely (Palo Alto, California), Ruth Edelman (Denver, Colorado).

Ruby Holden (South Wilmington, Illinois) was absent from this group picture because she was among the group of 14 who arrived in October. She is shown on the inset. [The group picture is courtesy of Dorothy Bradbury, and the inset picture is courtesy of Ruby (Holden) Franklin.]

On 4 September, 1943, a class that consisted of 425 U.S. Air Force cadets, 45 (male) naval officers, 14 WAVES (soon to be 21), and an unknown number of civilians and foreign students, began the 9-month training program. Most of the military students were temporarily housed in the International House or in the basement of the law library when they arrived on the U of C campus. Some were subsequently moved to South Side hotels such as the Miramar, Wedgewood, and Windermere. The WAVES were housed together in a hotel that was five blocks from campus.

The U.S. Air Force cadets, the naval officers, and the WAVES marched to their classes from the various hotels. Lectures consumed the morning hours (0800-1200), while the afternoons (1300-1700) were reserved for synoptic laboratory. During the intensive period of training at U of C (1943-early 1944), there were overlapping groups of trainees totaling about 1500 at any given time. Lectures were held in Mandel Hall, and a typical class size was 500 students. Mary Lockhart, one of the cadets, shared her memory of the classes at U of C:

While I still did not know what meteorology was about, we started a "lab" program which continued every afternoon all year. The first time we were given a coded map on which to draw fronts and isobars I thought "this is loads of fun, I hope we do it again." To my delight, we did it almost every day for the rest of the 9 months. I was glad to have been assigned to the University of Chicago because that school . . . emphasized the use of upper air weather maps. At the time it mainly meant the 10,000 ft level. I was also glad to have professors Byers, Starr, and Rossby whose teaching I greatly admired. . . . We had a 2 or 3 hour exam every Monday morning. Since I was fascinated with the subjects, I didn't mind the strain of the heavy schedule. Half way through the program, they dropped the bottom third of the students. I was glad to have survived the cut. I loved most of the courses, but because I was rusty on my math, I found dynamics very difficult. (Lockhart 1994, personal communication)

Another cadet, Barbara McClincy, shared that she was excited about delving into a completely new field of work— especially where math was involved. However, she also felt a little apprehensive about the tremendous responsibility in forecasting, especially during time of war. "I wanted to learn my lessons well" (B. McClincy 1994, personal communication).

Rossby's convivial nature helped break the strain of the demanding academic schedule. As remembered by Bradbury:

Rossby noticed that we [WAVES] looked worn out and in need of some entertainment. So he talked to the people working on the reactor project [atomic fission project under Enrico Fermi's direction] and we got together with a bunch of young physicists for a dance.

The teaching faculty at the Institute of Meteorology during the 1943-1944 academic year was full of well-known professors, including not only Rossby, but also Victor Starr, Horace Byers, and Verner Suomi. But it also included a number of instructors. In most cases, these instructors were the outstanding graduates from earlier sessions of the cadet program. They were retained to help with the ever increasing enrollments. Note that several women were among this group: Mildred Boyden (later Oliver), Josephine Peet, and Eleanor Hanson. In addition to her job as instructor, Boyden was also an important contributor to the mobile ballooning work and single-station analysis research that was conducted at U of C during the war years.

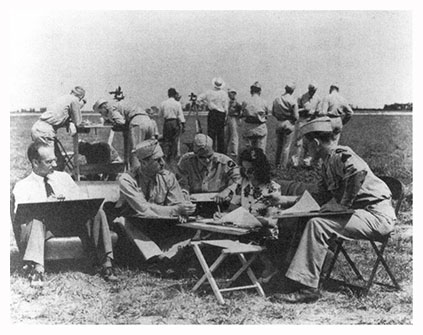

Mildred Boyden is shown here sitting with other instructors at Jackson Park while students can be seen in the background.

Theodolites (the optical devices on tripods) and plotting boards are being used to calculate upper-air winds by tracking pilot balloons.

On 5 June 1944, the day before D Day, the September 1943 class held their graduation ceremony.

Duty assignments for the WAVES

Following graduation, the WAVES from MIT, UCLA, and U of C were sent to the West Coast. Approximately half were assigned to the Naval Air Station (NAS)/ Moffett Field in the San Francisco Bay area, and half went to the NAS/San Diego (North Island). After a month, the two groups exchanged locations. At these stations, the WAVES performed forecasting duty under supervision. They forecasted weather for navy aviation including the lighter-than-air blimps that were patrolling the eastern boundary of the Pacific Ocean in search of submarines. As recalled by Eleanor Longbrake, "the biggest task seemed to be forecasting strong offshore winds that would be very hazardous for the blimps. . . . Fog forecasting was also important." After two months of supervision, the WAVES were individually assigned to naval bases in the United States. Most were promoted to lieutenant (junior grade) at this stage, although some attained the grade earlier because of age and experience at the time of graduation from officer candidate school.

One of the WAVES, Mary Lockhart, recalled her experiences in the field:

I went to NAS Hutchinson, Kansas, where four engine bomber pilots were trained. I stood forecasting duty for both local and cross-country flights. We worked 9 hours on and 23 hours off and no weekends or holidays off. I could never adjust my sleeping to this daily change . . . so became extremely tired, but still thought the work fascinating. For two months I was assigned to teach forecasting to enlisted men who were to be sent to isolated observation and forecasting posts. After a year, I was transferred to Glenview NAS [Illinois] which carried on basic flight training with Steerman aircraft. . . . Flight clearance weather for cross-country flights was also handled at Glenview as well as supervision of enlisted observers. (M. Lockhart 1994, personal communication)

Eleanor Longbrake, another WAVE forecaster, shared the following memories:

My permanent assignment was at Naval Air Facility, Columbus, Ohio. The navy shared the runways and control tower with the commercial airlines at the civilian airport... but we had our own weather station, operations office, etc. We had different weather concerns because of our large number of light planes that had to fly contact and couldn't cope with the thunderstorms or low ceilings We received a steady stream of planes from a local factory and one in Akron.

The planes underwent test flights before being ferried out. After the operations department got radar, our responsibility in regards to thunderstorms was reduced to identification of conditions that produced them. (E. Longbrake 1994, personal communication)

The male naval officers who had just completed the cadet program were not sent to NAS Moffett or San Diego. Rather, they were sent directly to their permanent assignments. As recalled by Longbrake, "I speculated as to whether the policy was to fortify us against possible discrimination on the next base, or to delay our arrival, making it easier to place us where we would not be senior officer in aerology on the base—or some other reason. It could not have been based on grades." An experience by Lockhart confirms Longbrake's conjecture:

When I reported to the Aerology office at my first duty station, NAS Hutchinson, I was senior ranking officer. However, a man a few months my junior was designated Officer-in-Charge. (M. Lockhart 1994, personal communication)

Post War WAVES Careers

After the war, the uncertain future of the reserve program forced many women out of the meteorological field, or put them into junior positions below their experience level. They took their knowledge to a variety of other fields ranging from anatomical drawing to teaching. Others tried their best to remain dedicated to the field of meteorology. Mary Lockhart took a job with the Thunderstorm Project under Horace Byers at the University of Chicago. Two years later (1948) when the Berlin Airlift got underway, she returned to active duty in the Naval Reserve at NAS/Pensacola, Florida. She managed the meteorology office at Pensacola for nearly four years. She was then transferred to the Naval War College for non meteorological duty. In 1954, the navy underwent a reduction in size following the Korean War, and Lockhart was released to inactive duty. She eventually established a career as a technical writer in the computer science field.

Another one of the cadets was Dorothy Bradbury. She requested discharge from the WAVES in 1946 and enrolled in the mathematics department at the University of Illinois. She was employed as a teaching assistant and soon found that pure mathematics had lost some of its appeal in the aftermath of her experiences as a forecaster. She decided to try to get back into meteorology and wrote to Professor Byers at Chicago. He encouraged her to return to graduate school at U of C and offered support from U.S. Weather Bureau contracts. Dorothy accepted a research assistantship and began to work with Erik Palmen. She worked on analysis of the jet stream and obtained her M.S. degree in 1951 under Palmen's guidance. She remained at the University of Chicago as a research scientist until retirement in 1974. Bradbury has made important contributions to a variety of subjects in synoptic and mesoscale meteorology. In succession, she worked with Palmen, Sverre Petterssen, and Tetsuya Fujita.

But whatever their destinations turned out to be, these women all helped chart new paths for the field of meteorology.

This article was abridged and adapted specifically for the AMS Weather Band. Any omissions or errors may be attributed to AMS staff. Copyright remains with the AMS