How Did Barometers Change Hurricane Research? Lessons from 1600s Barbados

- By AMS Staff

- Dec 2, 2021

"I believe, there might be excellent use made of the Barometer for predicting of Hurricanes, and other Tempests, especially at sea; since I am credibly informed, that a person of quality, who lives by the sea-side...can by the Barometer almost infallibly foretell any great tempest for several hours before it begins.”

This statement from Ralph Bohun in 1671 is one of the earliest suggestions in scientific literature, if not the earliest, of using the barometer for detecting and forecasting tropical cyclones. Interest in the hurricane had grown rapidly in England partly due to the destruction of an English invasion fleet off of Guadeloupe in 1666 (London Gazette, 3 and 13 December 1666), and a spate of storms from 1666 to 1671 in New England, Virginia, Bermuda, Newfoundland, and the Lesser Antilles (approximate storm locations between 1666-1671 shown below).

Before 1660, the barometer was used to investigate theories about vacuums in nature and whether the mercury in the instrument was supported by the weight of the air. By the early 1660s, two Royal Society members, Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke, discovered that atmospheric variations in weather had some relation to the level of the barometer. Boyle and Hooke coined the terms barometer and baroscope, respectively (Golinski 1999). Daily diaries of the state of the weather and barometer further assisted in showing how changes in the weather were related to atmospheric pressure fluctuations and the barometer's potential for weather forecasting (Vogel 2002). Increased interest in and use of barometers had, by 1670, led to their commercial production (Middleton 1964), although details prior to the early 1680s are scant (Golinski 1999; Vogel 2002). Together, this new instrumentation, scientific inquiry, and large monetary losses incurred by government and merchants as a result of hurricanes are likely motivating factors behind Bohun's hypothesis of using the barometer in their forecasting.

In August 1674, Dr. Thomas Townes wrote to Dr. Martin Lister, a fellow of the Royal Society, about "great damage" done on the island of Barbados by a hurricane that "whirled us about like a top from all points of the compass" soon after his arrival on 17 August (Stearns 1970). The following year, Lister and other Royal Society members likely read accounts of a "very violent hurricane" at Barbados on 10 September that threw down over 300 houses, killed about 200 persons, and cast away eight ships and five ketches with the loss of life of most of the seamen (London Gazette, 6 December 1675).

The two hurricanes at Barbados (the most prosperous of the English colonies at this time) and the desire of the Royal Society to have scientific contacts in the American colonies made Barbados a logical choice for inquiry. So the Royal Society made arrangements for barometers to be shipped to interested correspondents. By December 1677 a number of barometers were reported shipped to Barbados "to examine whether they would be of any use for the [sic] foretelling the seasons and mutations of the weather as they are found to do here, especially concerning hurricanes" (Stearns 1970).

Colonel William Sharpe’s Letter to the Royal Society

In late 1680, the Royal Society received a letter from Colonel William Sharpe of Barbados. The cover letter was dated 26 August 1680 and came with a set of daily barometer readings and wind and weather observations from 18 April to 24 August 1680.

Sharpe was one of the leading planters in 17th-century Barbados (Dunn 1972) and the Speaker of the Barbados House of Assembly in 1676-78 and 1682-83. It seems likely that the original shipment of barometers to Barbados in 1677 did not reach him until 1680, as the wording in his letter suggests he received the barometer only shortly before he set it up in April 1680. He addresses the interest in "foretelling the weather" so the barometer and letter may have passed through several unwilling or uncomprehending hands before it reached Sharpe. Sharpe refers to "... my own ignorance and not having the conversation of any one man of experience here . . ." (Sharpe 1680), which supports such a scenario.

Sharpe's barometer was a mercury barometer and likely a cistern type that was commonly manufactured at the time (Middleton 1964). The barometer was graduated in inches and tenths. The location of the barometer is assumed to be at Sharpe's plantation located on the rolling east facing slopes east of the central highland of Barbados. The highest elevation of Barbados is over 1100 feet above sea level in the region west of Sharpe's plantation.

Sharpe's barometer was a mercury barometer and likely a cistern type that was commonly manufactured at the time (Middleton 1964). The barometer was graduated in inches and tenths. The location of the barometer is assumed to be at Sharpe's plantation located on the rolling east facing slopes east of the central highland of Barbados. The highest elevation of Barbados is over 1100 feet above sea level in the region west of Sharpe's plantation.

Sharpe's letter is of substantial interest for historians of tropical meteorology and the history of science. He observed the diurnal cycle of pressure, noticed strong winds continued with both the falling and rising of pressure associated with a tropical cyclone, attributed the small variation in pressure values to the constancy of the wind direction, has an interesting description of the appearance and shape of trade wind cumulus clouds at a time when no systematic classification of cloud types existed, patiently awaited the hurricane season to check the barometer's performance during the passage of a tropical cyclone, and closely observed pressure fluctuations at a finer level of precision than the instrument was marked, rightly noting that these small variations were significant.

The Pressure Series, Winds, and Rainfall, April-August 1680

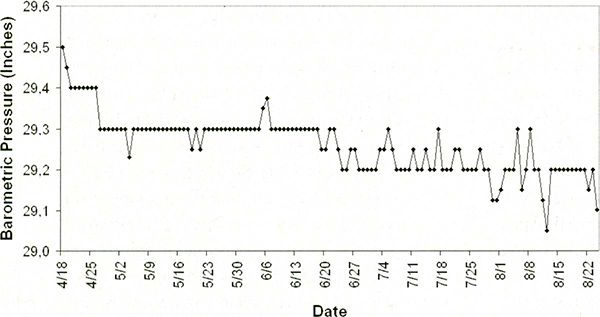

How reliable is Sharpe's weather record? The graph below presents the daily pressure values, recorded at 0900 local time each morning by Sharpe from 18 April to 24 August 1680. The record indicates evidence of two steplike declines in pressure, the first from 18 to 26 April of 0.2 in. and the other in the second half of June of 0.1 in. We can only speculate on the causes of these declines, but the formation of air bubbles in the mercury column is possible. These changes in pressure do not seem to have otherwise affected the performance of the barometer. The average pressure for the entire 129 days is 29.26 in. There are 40 days with a 4 P.M. observation added by Sharpe. In 12 instances there is a pressure fall from 9 A.M. of 0.1 in., in 12 instances a fall of 0.05 in., and in one instance a fall of 0.025 in. The average fall in pressure from 9 A.M. is 0.07 in. By applying this average difference, the average daily pressure from the mean of 9 A.M. and 4 P.M. is 29.23 in.

Assuming that sea level pressure for the months of April through August is approximately the same today as in 1680 because of the relative invariance of pressure near the equator, the elevation of Sharpe's barometer can be approximated by using modern data to calculate the difference between station pressure and sea level pressure at the known elevation of the modern site and applying this difference between Sharpe's station pressure (29.23 in.) and the assumed sea level pressure of 29.96 in., which gives a difference of 0.73 in. This gives us an estimated elevation of 708 ft above sea level, which is consistent with the location of his plantation relative to sea level and the central highland of the island. Due to the uncertainty caused by the steplike drops in pressure, the estimate has a margin of error on the order of tens of feet.

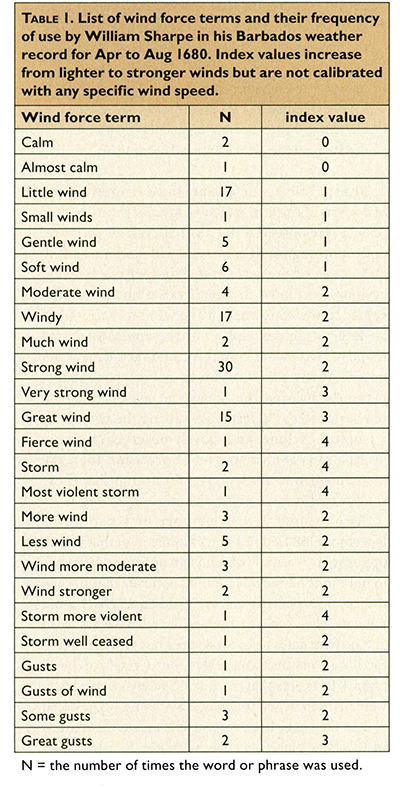

Wind direction is consistent with what would be expected in the Tropics—a persistent easterly wind flow. It’s not clear what the wind speeds were, as Sharpe used nonstandard terms to describe their force. All together, he used 14 distinct wind force terms, four terms for wind gusts, and six terms to describe a “change in strength.” Three of his 14 wind force terms and one of his gust terms are used only during the hurricane of 12-13 August. His terms have similarity with terminology in use by contemporary mariners (Lamb and Frydendahl 1991; Chenoweth 2006), but there is no obvious correspondence with a set list of terms in use at the time.

Four wind force terms, "little wind (or "wind little")," "windy," "strong wind," and "great wind" account for 79 of the 135 wind force terms in the Sharpe record and probably correspond, along with "much wind" and "very strong winds," to the most common range of trade wind speeds (very roughly, on the order of 5 to 25 kt). Other terms clearly indicate light wind speeds ("almost calm," "small winds," "gentle winds," "soft winds," and "moderate winds"). The three gust terms "gusts," "gusts of wind," and "some gusts" are unremarkable in apparent intensity.

Four wind force terms, "little wind (or "wind little")," "windy," "strong wind," and "great wind" account for 79 of the 135 wind force terms in the Sharpe record and probably correspond, along with "much wind" and "very strong winds," to the most common range of trade wind speeds (very roughly, on the order of 5 to 25 kt). Other terms clearly indicate light wind speeds ("almost calm," "small winds," "gentle winds," "soft winds," and "moderate winds"). The three gust terms "gusts," "gusts of wind," and "some gusts" are unremarkable in apparent intensity.

The remaining wind force terms and gusts coincide with the August hurricane and the lowest pressure of July 1680. "Great gusts" occur on 30-31 July, with the lowest pressures of that month and may be associated with a tropical cyclone of unknown intensity passing to the south of Barbados. The remaining terms "fierce wind," "storm," and "(storm) most violent" occur with the August hurricane. August featured very light winds, other than from the hurricane, unlike the steadier and stronger winds of the previous three months.

Sharpe also recorded rainfall during this period, with the number of rain days per month ranging from 3 in August (first 24 days only) to 13 in June. August was notably drier than the other months with the only significant rains coming in the hurricane.

Sharpe's observations, with respect to the climatology of Barbados, show signs of being as reliable and accurate as his perceptions, scientific ability, and instrumentation allowed. There was a drop in pressure that is inconsistent with the rise in wind speed from April through July. This can be explained as probably being due to an air bubble (s) in the mercury column. The diurnal variability appears to have been unaffected. This is a weather record that can be trusted and valued.

The Hurricane of August 1680

Sharpe's patience in waiting for "tempestuous weather" paid off and during the night of 12-13 August, a hurricane passed north of Barbados. Sharpe has the distinction of making the first measurement of pressure within the circulation of a tropical cyclone yet documented for anywhere in the world (Bartolache 1772; Stearns 1970; North 1979; McClellan 1992). Sharpe's record affirmed the usefulness of the barometer in detecting and forecasting a hurricane.

Sharpe makes no comments on damage done in the storm. The lowest barometer reading, with corrections applied, was 29.71 in. Using the pressure-wind speed relationship for the Tropics for low latitudes (from Table 3 of Landsea et al. 2004) to estimate wind speed from a peripheral pressure data point in a tropical cyclone gives a wind speed of around 39 mph or 34 kt. Given the location of the hurricane to the north of Barbados, the weaker sector of the storm, moving west by north or west-northwest, gives a wind speed estimate at the threshold of 34 kt for a tropical storm, indicating minimal tropical storm force sustained winds.

This is consistent with government accounts from Barbados found in the Calendar of State Papers, CO 1/46 No. 5 (Public Record Office 2000), in which officials report the storm was not violent at Barbados and make no mention of storm damage on the island. These same reports mention that stormy weather was felt at St. Kitts (St. Christopher) on 13 August and that ships put to sea and two shallops were wrecked in the harbor "more by the sea than by the wind." Furthermore, at Martinique the most violent hurricane ever known there to that time was reported to have knocked down all the houses, forts, and churches and hardly a tree or plant was left upright. Over 20 ships were lost in the cul-de-sac, including two English ships. Judging from the Barbados weather record, the storm struck Martinique during the early morning hours of 13 August between about 2:00 AM and 8:00 AM local time.

This storm continued on its course to the island of Hispaniola, where it was felt severely at Santo Domingo (Anonymous 1680) and also destroyed French shipping on the western side of the island (D'Estrees 1680). There is no trace of the storm yet to be found in Cuba, Florida, or the English colonies. There is a possibility that this storm made no further landfalls.

After the Hurricane

Sharpe's letter arrived in London in 1680 during a hiatus in the publication of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (hereafter Transactions), which did not resume until 1681. In 1685, the first journal of barometer readings, made in England in 1684, was published (Plot 1685). Had the Transactions been actively publishing in 1680, it is likely that Sharpe's record would have been the world's first published barometer journal.

In the mid-1680s, two papers (one in England and the other in France) initiated a debate about the nature and origin of the trade winds that was then taken up by Edmond Halley in the Transactions in 1686 (Persson 2006). Halley had access to Sharpe's letter and almost certainly read it in preparing his paper as had Lister (1684) in his paper on the barometer and its connection with weather fluctuations. Halley makes reference to "the true reason of the rising and falling of the mercury, upon the change of weather" and the "very low" descent of mercury during hurricanes (Halley 1686) and cites his own observations on St. Helena and others at Barbados. Although Sharpe is not named, there is no other source that could have supplied information on the state of the barometer during a hurricane. Also, Vogel (2002) mentions that Halley had examined newly received data from Barbados, along with his own data from St. Helena, and observed the small variation in the Tropics as compared to temperate zones. Here is an example of the contribution of "colonial science" in a major philosophical debate in Europe. Sharpe's record can now be identified as the Barbados source for Halley in establishing empirical distinctions between the Tropics and temperate zone.

On 21 November 1680, the Royal Society Journal Book indicates that a thermometer was sent to Sharpe (Stearns 1970). The shipment of the thermometer was doubtless in hopes of his continued observations of the barometer and thermometer and recognition of his success in performing cutting-edge empirical work with a new technology in a remote environment. Unfortunately, there is no further correspondence with Sharpe in the Royal Society archives. Sharpe continued to serve at various times in the Barbados colonial government and as acting governor in 1714-15. Sharpe may have considered his duty to science accomplished, having provided his answers to the Royal Society's letter, and ceased his observations. Although the record apparently ended in 1680, we can acknowledge Sharpe as a previously unrecognized pioneer in the history of tropical meteorology, the history of the barometer, and the history of science.

This article has been edited and adapted specifically for the AMS Weather Band from the article "A Pioneer in Tropical Meteorology: William Sharpe's Barbados Weather Journal, April–August 1680" by M. Chenoweth, J.M. Vaquero, R. García-Herrera, and D. Wheeler. Any errors or omissions may be attributed to AMS Staff. Copyright remains with the AMS.