How Blue Can A Blue Norther Be?

- By Bob Henson

- Nov 22, 2022

Temperature swings can be subtle, stunning, or somewhere in between, depending in large part on what you’re used to. In a moist tropical climate, like the one that prevails over much of Hawai’i, the typical difference between nighttime lows and afternoon highs may be less than 20°F. In some locations, this is even larger than the difference between the coolest and warmest month, leading to the old saying that “night is the winter of the tropics.”

For a parched contrast, let’s consider the semiarid climates just to the east of the central and northern Rockies. Here, a downslope chinook wind can send the temperature rising by 20°F or more in a matter of minutes. Spearfish, South Dakota, famously rocketed from –4°F at 7:32 a.m. to 45°F in at 7:34 a.m. on January 22, 1943.

Growing up in Oklahoma, where air masses regularly jostle for position across the open plains, I marveled at the rapid temperature swings produced by cold fronts. The most dramatic of all were the “blue northers”, the fast-moving fronts of autumn that can sweep across the unobstructed landscape from North Dakota to north Texas in a single day, sometimes moving at close to highway speeds. The name originates from the gunmetal blue-gray clouds that typically form along and just behind the surface front.

Once, on November 11, I remember my favorite childhood weathercaster, the late Jim Williams, commenting on the fact that Oklahoma City’s record high of 83°F and its record low of 17°F occurred just hours apart on the same date. That was November 11, 1911 (or 11/11/11), a date that Oklahoma state climatologist Gary McManus has dubbed “a palindrome to remember.”

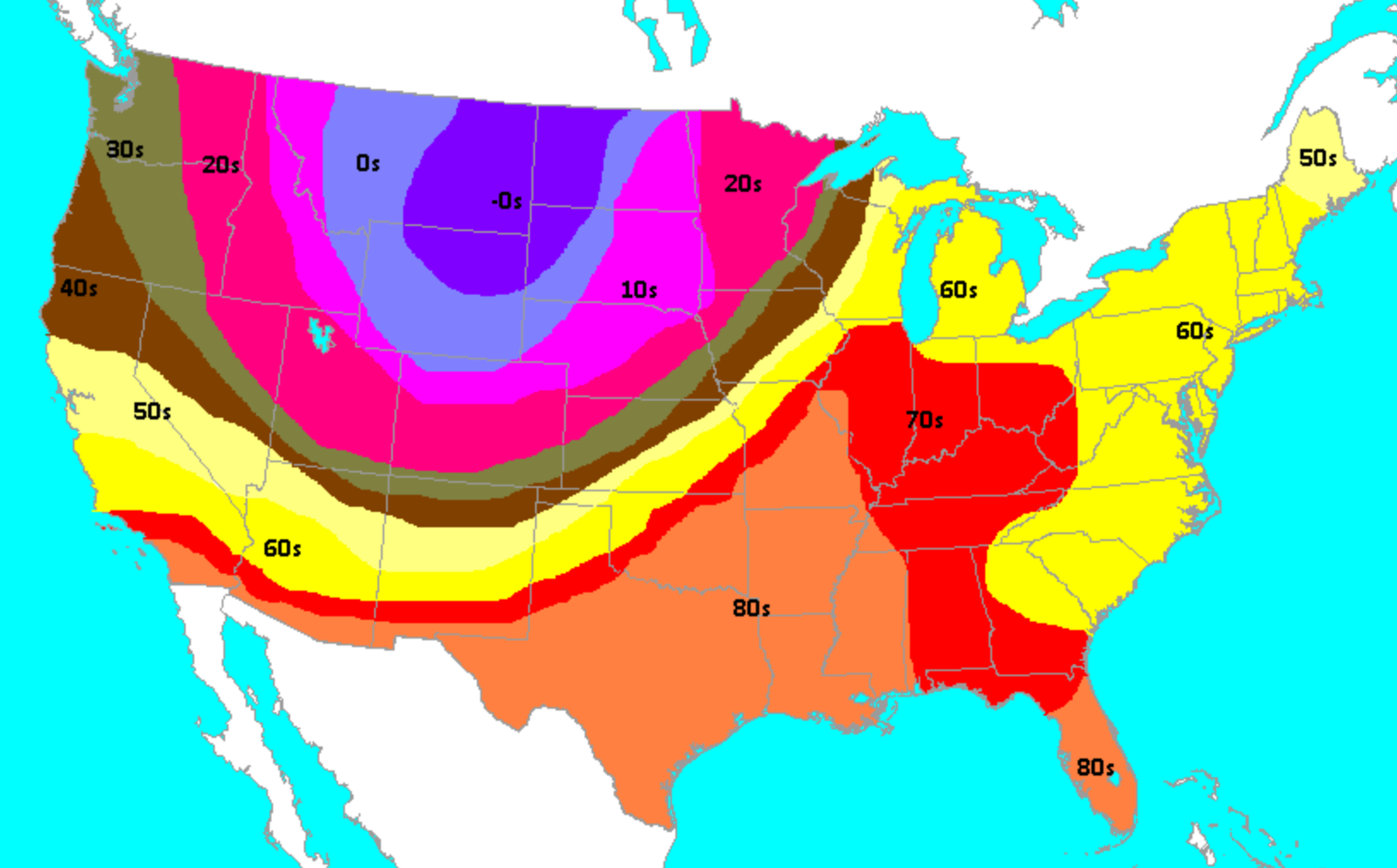

Daily high temperatures on November 11, 1911, stayed below 0°F over parts of the northern High Plains, while they soared above 80°F from most of Texas to southern Missouri and Mississippi. (NWS/Louisville, KY)

This bluest of all blue northers in U.S. history—sometimes called the Great Blue Norther of 11/11/1911—turned a springlike Saturday into a bone-chilling Saturday night for millions of people across the central United States.

As the cold front and associated upper-level storm swept across the nation, they spawned a major autumn tornado outbreak from Illinois and Iowa to Michigan. At least 13 people were killed by at least nine significant tornadoes that day, including three rated F3 or F4 on the Fuijita scale. The worst was an F4 that plowed through Rock County in southern Wisconsin, where rescuers and survivors were engulfed in blizzard conditions less than an hour later.

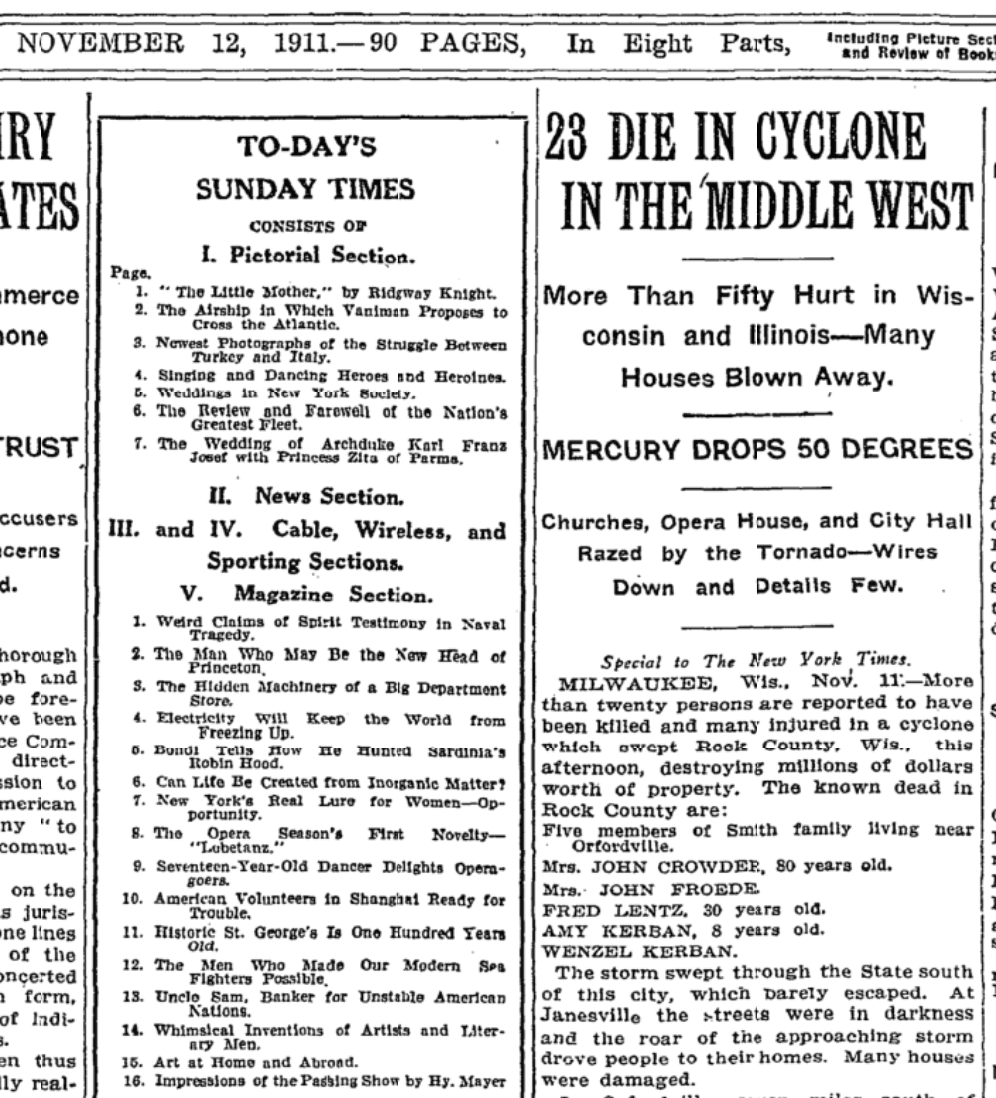

The twisters rated front-page mention on the New York Times on November 12, 1911, in an article headlined “23 DIE IN CYCLONE IN THE MIDDLE WEST”. (Tornadoes were often called cyclones in the early 1900s, as in the film The Wizard of Oz; the death toll from this outbreak was later lowered.)

An excerpt from the front page of the New York Times on Sunday, November 12, 1911. (NYT TimesMachine)

Tornadoes do happen in the central United States in autumn, though seldom so far north. The Times’ subhead (secondary headline) alluded to what was even more unusual about this particular weekend: “MERCURY DROPS 50 DEGREES.”

Indeed, many locations saw temperature drops of 50°F and more in less than 24 hours. The most dramatic drop-offs were in a belt from Oklahoma to Missouri, where some locations saw temperatures plummet more than 60°F in less than 12 hours.

Temperature drops (in degrees Fahrenheit) observed with the passage of the Great Blue Norther of November 11-12, 1911. (Image credit: NWS/La Crosse, Wisconsin)

From Missouri east and north, the frontal passage was quickly followed by bursts of sleet and snow. Columbia, Missouri, went from 82°F at 2 p.m. to 38°F at 3 p.m., with sleet falling by 4 p.m.

In Springfield, Missouri, a record high of 80°F around 3:45 p.m. was followed by a record low of 13°F just before midnight. By morning, it was 9°F, and the next day’s high was a mere 21°F.

Springfield’s experience on November 11 was recounted at a website produced by the National Weather Service office in Louisville, Kentucky: “Winds to 54 mph for five minutes with gusts to 74 mph accompanied the passage of the front, causing damage to buildings. Thunderstorms brought hail, followed by rain, which turned to sleet less than two hours after the 80° reading earlier in the afternoon.”

In Louisville, “on the morning of the 12th the temperature fell from 74° at midnight to 50° at 1am, and was into the mid 20s by the time the sun came up that morning. Winds to 48 mph accompanied the front around 12:30am. When Louisville was in the mid 70s at midnight, Saint Louis was in the upper teens.”

In Columbus, Ohio, where early-morning temperatures on November 12 were around 70°F, the front arrived at 3 a.m. with an intense thunderstorm that tore down trees and power lines. According to a local history website, “Columbusites who had been walking around in shirtsleeves on Saturday afternoon made their way to church Sunday morning in a light snow, with ice forming on the puddles, and a bitter wind blowing out of the northwest.”

The dual records of 11/11/11 stood in Springfield, Missouri, for many decades. The pairing was eventually disrupted when the record high of 80° was tied on November 11, 1989. The low of 13°F hasn’t yet been tied or broken, though.

In Oklahoma City, the dual records both remain untouched. If this ever changes, it’ll most likely be because of warmth, as was the case in Springfield. Eleven of Oklahoma City’s 30 daily record highs for November have been set since 2000, compared to just one daily record low.

At least for now, these intact twin records from 11/11/11 are like a pair of weather-beaten historical markers along a dusty roadside, providing numerical testimony to just how intense an autumn cold front can get in the Great Plains.

* Associated image provided by Robert V. Ruggiero on Unsplash