From Kamikaze to Katana: How Weather Protected Japan from Mongolian Invasion

- By J. Neumann

- Jun 4, 2021

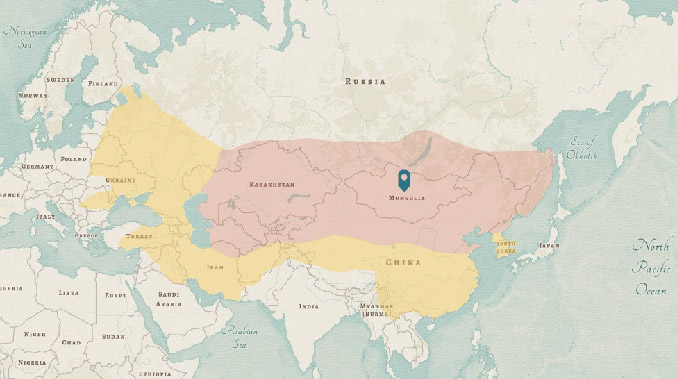

At the time of Genghis Khan’s death in 1227, the Mongolian Empire stretched east to west from The Pacific to the Caspian Sea and from southern Russia to Tibet. In the next 30 odd years, Mongolian leaders expanded the empire in all directions, with periodic contractions back to the capital of Karakorum in order to debate succession and crown a new great khan.

Pink shows the approximate extent of the Mongolian empire in 1227 at the death of Genghis Khan. Yellow shows the approximate boundaries at the largest extent of the empire after his death.

As expansion was taking place in all directions, neighboring empires watched nervously to see if they would be the next target for invasion. The Mongolian advance into the east was slow, as they grappled with Chinese forces, but eventually the northern part of the country was added to the empire of Ogedei Khan, son of Genghis. With this addition, and the Korean peninsula as a vassal state, warlords in Japan began to take note. Ever since the Japanese had been defeated by Chinese forces on the Korean peninsula, the Japanese feared that Korea could serve as an assault base for a powerful enemy determined to conquer Japan. The peninsula is separated from the Japanese isles by a strait of only about 150 km in width. And as the Mongolian empire expanded seemingly unstoppably, the threat of a Mongol invasion loomed large in Japan's eyes.

It wasn’t until 1259, however, when Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, ascended the Mongol throne that the threat to Japan became concrete. Though he held the title of great khan, Kublai in reality held power only over the territories of Mongolia and China. A brutal civil war over who would be declared the great khan lasted until 1264, and in its aftermath, Kublai remained in control of only one quarter of the vast Mongolian empire. The rest was divided among three other descendants of the great Genghis. With his pathways west and north substantially blocked by these other rulers, Kublai turned his sites to eastern expansion. He established the Yuan dynasty in China and declared himself the Emperor of China (though southern China was not subjugated by him until 1279).

Having strengthened his ties to Korea through marriage, Kublai next sent envoys to Japan, accompanied by Korean officers as guides. They carried a dispatch calling on the “King of Japan” to submit or have his country invaded. The ambassadors set off from a Korean port in 1267, but weather conditions at sea forced the mission to return to the peninsula.

It appears that in subsequent years, up to 1274, Kublai directed five more embassies to Japan which were never permitted by the Japanese to reach either Kyoto, the imperial capital, or Kamakura, the seat of the Bakufu (military, or “tent,” government; “Kamakura Shogunate”). In 1268 the emissaries were held up at Dazaifu, the residence of the so-called Western Defense Commissioner on Kyushu island. The Khan's dispatch was transmitted to Kyoto, where the Emperor and Court, seized by apprehensions, drafted a conciliatory reply. At the time, however, the Emperor was mostly a figurehead. The real power rested in the hands of the Bakufu which was headed by a military Regent (Hojo Tokimune). Because of this, the imperial reply was forwarded to the military Regent who chose to ignore it. In an expression of his contempt for the Mongol threat, the Regent had the ambassadors summarily deported, a fate which befell subsequent missions of Kublai prior to 1274. In anticipation of the invasion, the Bakufu then undertook various defense preparations.

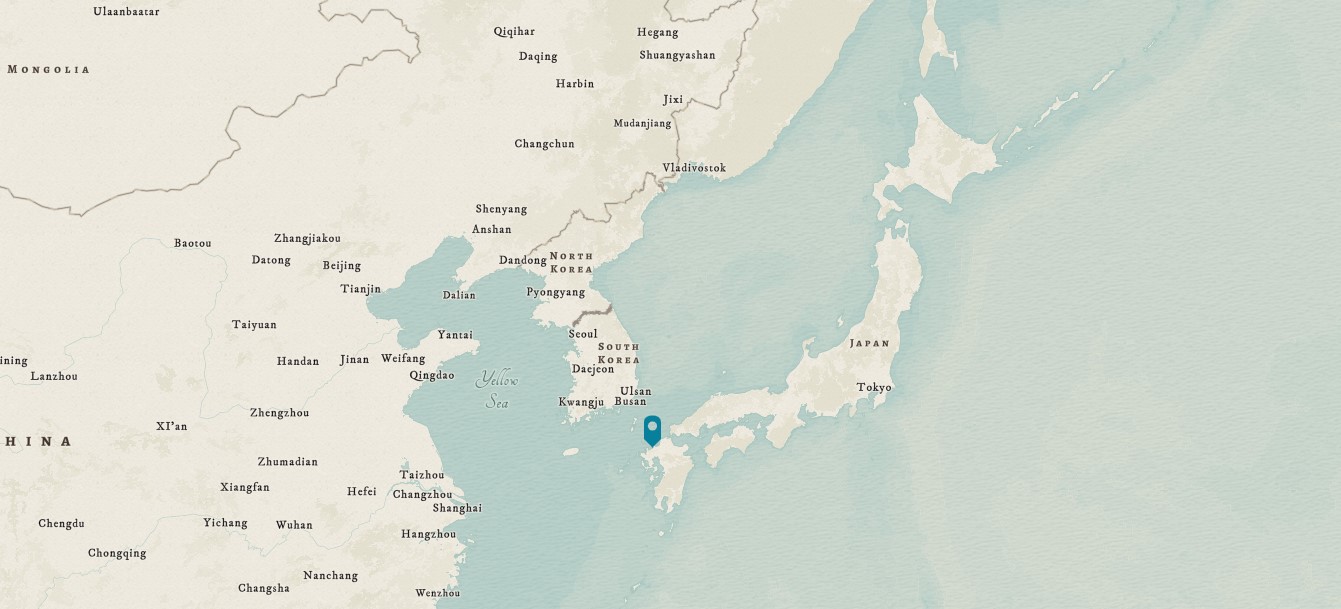

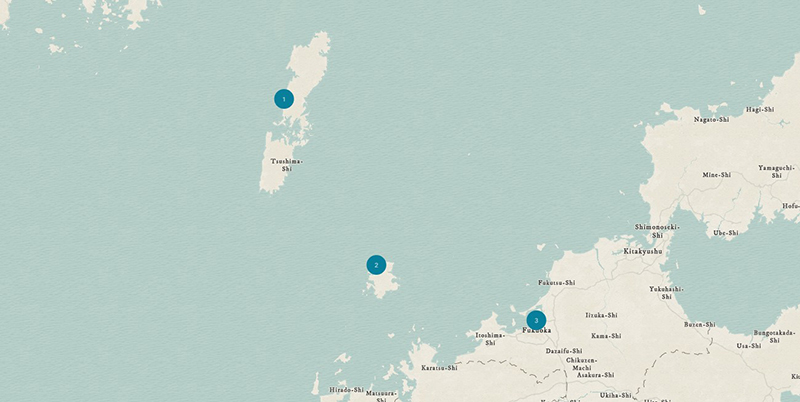

The Mongolian fleets targeted a harbor in Japan that was close to the Korean peninsula for their invasion

1274: The First Invasion

To expand his empire into Japan, Kublai Khan needed ships and sailors (as well as soldiers). The Mongols, however, were an inland empire. They had skills on horseback, archery, and artillery warfare. They were not shipwrights, nor did they possess a knowledge and experience of seafaring. The Khan, therefore, ordered the King of Korea to build warships, and to raise a force of fighters and crews to operate the ships. In addition, extensive areas of the peninsula were planted with rice to feed the forces.

Finally, in November 1274 an armada put to sea from a port in Korea. Estimates for the number of troops and ships differ depending on sources, but there may have been up to 40,000 men, including 15,000- 20,000 Mongol and Chinese soldiers; 8,000 Korean troops; and some 7,000 Korean and Chinese sailors. Some counts include 300 "large" ships and 400 to 500 small craft.

Kublai's armada first overran the Japanese garrisons on the islands of Tsushima and Iki (marked #1 and #2 on the map below), off the northwest coast of Kyushu. On 19 November they landed at Hakata and Imazu on Kyushu proper (marked #3 on the map below). In the first engagements, the Mongolians cut down Japanese troops easily and advanced through Hakata. In these battles, the Mongols were at an advantage because of their firepower. They had composite bows and slings which outranged the Japanese, and included poison and fire-tipped arrows as well as explosive devices and an early type of grenade. But despite their initial success, the weather proved to be one factor they could not overcome.

Sir George Sansom, a British diplomat and scholar of Japanese history, offered this vivid description of the events of 19 November: It looked as if the whole Kyushu force would have to fight until near annihilation, so as to give time for the arrival of reinforcements which then were approaching from the central and eastern provinces. Despite their failure at Hakata, however, the Japanese were by no means defeated, since given time they could overwhelm the Mongols by superior numbers. As it turned out, such desperate measures were not needed, since luckily for the Kyushu men, that night as they lay exhausted and drenched in their dyke a great storm threatened and the weather-wise Korean pilots pressed the Mongol generals to re-embark their army, lest they should find themselves isolated on shore, their ships on the rocks and all possibility of retreat cut off. The storm and the fear of a night attack by the Japanese led the Mongol commanders to order a general re-embarkation and sail-off.

Sansom continues: Fortunately for them [the Japanese], when daylight came they saw the last stragglers of the enemy fleet making out of the bay. One vessel at least ran aground on the Shiga spit, and many more sank in the open sea during the tempest—according to some accounts two hundred were lost. Korean records say that 13,000 men of the invading force lost their lives during this expedition, many, perhaps most of them, by drowning. The invasion had failed and the remnants of the Mongol force made their way back to Korea in disorder and distress.

Another historian mentions that as a result of the storm "One ship with about a hundred men aboard ran aground on Shiga spit . . . and these unfortunates were promptly captured, carried to Mizuki, and there put to sword. Many of the Korean vessels foundered on the open sea.”

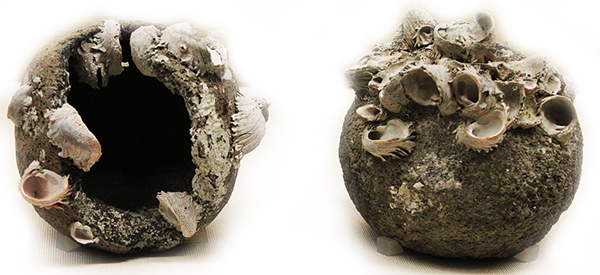

Mongolian grenades from the failed invasion were retrieved from a shipwreck off the coast of Japan and show barnacles growing on them. Image from Wikimedia Commons licensed under Creative Commons 3.0

1281: The Second Invasion

Disregarding the abilities and capacity of the Japanese, Kublai Khan believed that the failure of the invasion was due to the storm. In 1275 he sent another mission to Japan demanding submission. But instead of surrendering, the Bakufu executed these envoys. Greatly angered by the death of his emissaries, the Khan now intensified his preparations for a second invasion. He even set up an "Office for the Chastisement of Japan" for the supervision and coordination of the efforts by his court and by some of the vassals.

In 1279 Kublai conquered southern China and established the Yuan dynasty. This expansion considerably increased his maritime resources and manpower for the new invasion (the armor below is an example of equipment that Yuan soldiers wore during the invasion. Mongolian armies were often composed of a majority of newly acquired soldiers rather than native Mongolians. Image on Wikipedia, licensed under Creative Commons license 3.0).

In some of his messages, the khan even attempted to use the fact of South China's submission in order to intimidate the Japanese, but to no avail. In the meantime, the Bakufu worked, on its part, to build up Japan's military strength. As an additional measure, a defense wall was constructed along the Hakozaki Bay of Kyushu, including the area where the main Mongol invasion force landed in 1274.

In some of his messages, the khan even attempted to use the fact of South China's submission in order to intimidate the Japanese, but to no avail. In the meantime, the Bakufu worked, on its part, to build up Japan's military strength. As an additional measure, a defense wall was constructed along the Hakozaki Bay of Kyushu, including the area where the main Mongol invasion force landed in 1274.

The Khan's invasion forces embarked for Japan in 1281. Some 40,000 Mongols, Koreans and North Chinese sailed in about 900 vessels from Korea. A second force, believed to comprise some 100,000 men, departed from ports of the recently subjugated South China. The latter force was to rendezvous with the northern armada. Actually, the northern force was ready in spring and one speculates whether this time was chosen so as to reach Japan before the onset of the typhoon season. The southern force, however, was late: the actual invasion did not begin until late in June.

The samurai and the other Japanese warriors must have put up a most determined and effective fight as the invasion force was hardly able to make territorial gains for some six weeks. The combat was restricted to the coastal area of the NW Kyushu. The Japanese even dared attack the vessels of Kublai's armada with their "mosquito" fleet of small vessels. This is all the more astounding as it is almost certain that the invading armada must have had ships of considerable size for the times. Marco Polo, who arrived to Kublai's court in 1275, describes in his travel account that Chinese boats were large, being served by 200 to 300 seamen.

After prolonged fighting along the Kyushu coast, the invading army met with an even greater enemy than the Japanese troops. The month of August usually brings typhoon weather to the waters surrounding Japan, especially to the southwest. In 1281, as the invaders might have foreseen, a great hurricane arose and beat with violence upon the shores of Kyushu for two days. It came to be known in Japanese annals as the Kamikaze or Divine Wind, for it blew the enemy fleet to pieces.

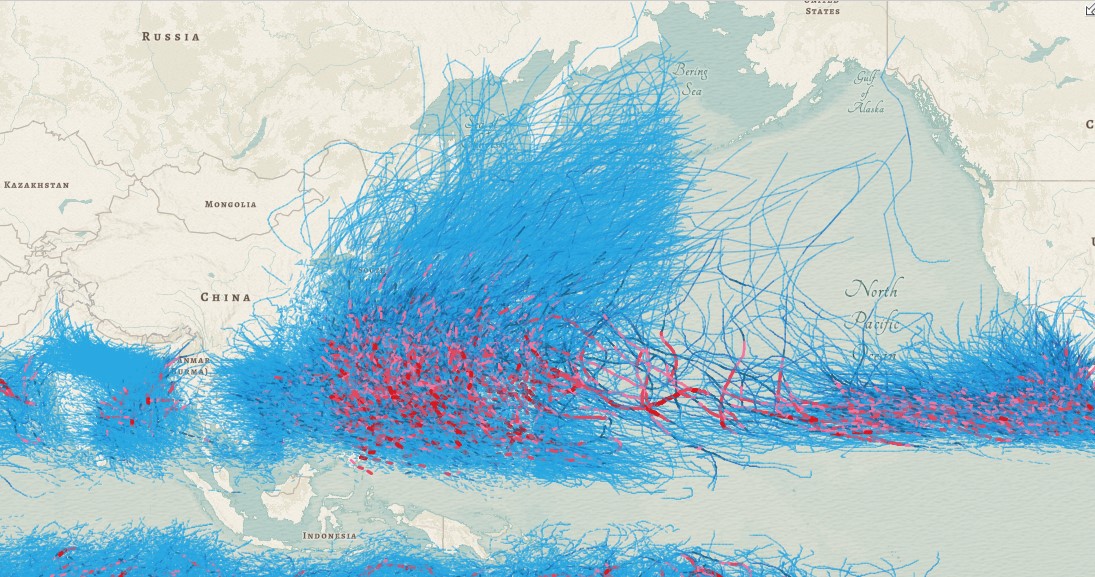

As these historic storm tracks from 1880 to 2020 show, Japan is no stranger to typhoons. Blue and red lines indicate storms of varying intensity.

The storm took place over the fifteenth and sixteenth days of August. How great the enemy losses were is not exactly clear, but the destruction appears to have been devastating. Most accounts agree that the Korean shipmasters, scenting danger, managed to get most of their vessels away from the shore before the tempest reached its height; but even so they are said to have lost on their flight more than one-third of the Korean and Mongol troops that they were carrying.

As for the southern fleet from China, the greater part of which was operating in the Gulf of Imari in Hizen, it was there exposed to the full power of an on-shore hurricane. When the escaping vessels in desperation made for open water, many of them were caught by tide and wind and helplessly jammed together in the narrows. Of those that got out to sea, many if not most foundered in the storm. The total loss of life must have been enormous. The Chinese ships had carried perhaps as many as 100,000 men, and certainly far more than half of these were drowned or slaughtered before they could embark. The main body of this Chinese armada had entered the Gulf of Imari soon after making its landfall. It had put ashore strong forces at several points along the coast of Hizen, and a numerous contingent occupied the island of Takashima, which lies at the entrance to the Gulf. Most of these men were unable to reach their ships, and thousands were killed or taken prisoner by Kyushu warriors who attacked here and elsewhere before the storm abated.

Contemporary Korean records describe some aspects of the disaster wreaked by the typhoon as follows:

A storm arose from the west, and all the vessels made for the entrance of the harbor together. The tide was running in very strong and the ships were carried along irresistibly in its grip. As they converged to a focus at the mouth of the harbor a terrible catastrophe occurred. The vessels were jammed together in the offing, and the bodies of men and broken timbers of the vessels were heaped together in a solid mass so that a person could walk across from one point of the land to another on the mass of wreckage. The wrecked vessels carried the 100,000 men from Kiang-nam (i.e. South of the Yang-tse Kiang).

The "harbor " here probably means Imari Gulf in northern Hizen, the entrance to which is protected by Takashima island (see Fig. 1). We have mentioned earlier that Marco Polo, the famed Venetian traveler, reached Kublai's court in 1275. As far as the fate of the second invasion is concerned, he writes the following:

“And it came to pass that there arose a north wind which blew with great fury and caused great damage along the coasts of the island, for its harbors were few. It blew so hard that the great Khan's fleet could not stand against it. And when the chiefs saw that, they came to the conclusion that if the ships remained where they were the whole navy would perish. But when they had gone about four miles they came to a small island, on which they were driven ashore in spite all they could do; and a large part of the fleet was wrecked, and a great multitude of the force perished, so that there escaped only some thirty thousand men, who took refuge on this island.”

All in all, with the force of the typhoons arrayed against the Mongolian armies, this became one of the most disastrous naval invasions in history. One other historical impact of these battles was the development of the famous katana sword. According to some historical accounts, the boiled leather armor that the Mongolians wore was too thick for samurai swords of the time and some actually snapped off. This led to a redesign of the Japanese swords to be shorter, with a wider tip, and very well tempered metal.

And one last note on the weather and climate: recent research argues that an unusually wet and mild climate over the central steppes during the life of Genghis Khan was responsible for increased food production, horse availability, and overall health and stability within the Mongolian homelands. This was one major factor that allowed the empire to flourish and expand across Asia and into Europe.

This article was edited and adapted specifically for the AMS Weather Band from an earlier article that appeared in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Any errors and omissions may be attributed to AMS Staff. Copyright remains with the AMS