Weather Bureau Office, Galveston. Tex., February 25,1928

Severe cold waves on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico are infrequent but of great moment. Human habitation and dress are not here adapted to extreme cold; cattle and other livestock are inadequately sheltered from winter extremes, and tropical fruits and winter truck are subject to extensive damage and occasional total destruction from abnormally low temperatures. In economic loss and human suffering, a severe cold wave, reaching our southern and southeastern borders, ranks with the hurricane.

In a treatment of cold waves that have visited the west Gulf coast area, one is concerned with atmospheric conditions over the continent and neighboring oceans. With a full realization of these difficulties, the writer attempts a description of severe cold waves in the area named, with an explanation of some cold-wave failures, together with criteria for forecasting temperature minima. Some of these rules may prove helpful. None is infallible.

Frequency of severe cold waves

A cold wave in the winter months, in the coast section of Texas, is defined by the Weather Bureau as a fall in temperature of 16° in a 36-hour period to a minimum of 32°. The severe cold waves discussed in the following have all far exceeded these limits both in rapidity of fall and in intensity of cold. Just what degree constitutes a severe cold wave is difficult to determine, but for the purposes of this paper, a fall of 20° to a reading below 25° is considered severe and a fall of 30° or more to a minimum below 20° is considered very severe.

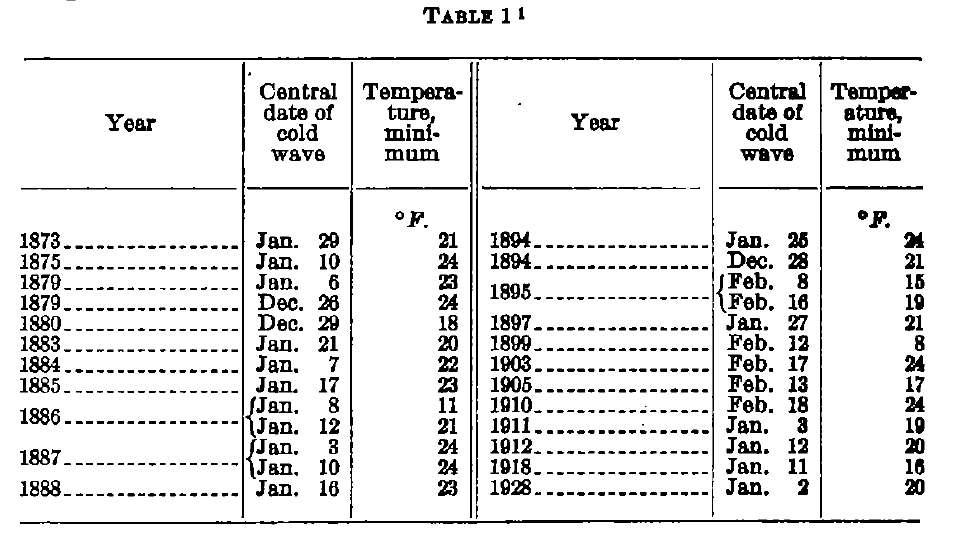

In the 57 years of record at Galveston, 1871 to 1927, inclusive, there have been 27 cold waves with temperatures below 25°. These include the cold wave of January, 1928, which set in on December 31, 1927, and reached a minimum of 20° on January 2. Also included as separate cold waves are those of 1886, 1887, and 1895, which came in pairs with short intermissions. Strictly, there were only 23 instances, as shown in Table 1. In seven of these instances, the temperature fell below 20°, counting the pair in 1895 as a single occurrence.

Dates of cold waves with minima below 25° at Galveston during years 1871 to 1927, inclusive. The last occurred in 1928, but the cold set in at the close of 1927.

The fall in temperature

From highest temperature on one day to lowest of the following, falls in excess of 50° have not been rare on the Texas coast. When the fall, in a precise span of 24 hours, from any hour to another of the same name, exceeds 40°, the cold wave is uncommonly severe. In January, 1918, at Galveston, the 24-hour fall amounted to 42°. In 12 hours, from 11 p.m. of the 10th to 11 a.m. of the 11th, the temperature fell from 63° to 16°, or 47° in 12 hours, and at the latter hour it is normally warmer in January than at 11 p.m. Ahead of cold waves in extreme southern Texas the temperature sometimes rises almost to midsummer heat. On December 13,1901, the temperature at Corpus Christi rose to 86° and at 7 a.m. the following day stood at 36° and on the 15th dropped to 20°. It seems doubtful that the greatest changes in northern latitudes, necessarily taking place at lower temperature levels, can so profoundly affect human comfort.

In January, 1886, at Galveston the temperature fell from a maximum of 65° on one day to a minimum of 11° on the following day, a drop of 54°. Such temperature drops are, however, decidedly unusual. Due to the greater diurnal range in temperature, such marked changes from the high temperature of one day to the low of the next are somewhat more common in the interior.

Origin of Texas coast cold waves

The anticyclone bearing winds of the Texas coast cold wave is of the type known as an “Alberta High.’’ It develops over an area embracing the western portion of North Dakota and Montana or, as is more frequently the case, moves in a southerly direction from the British northwest, crossing the Canadian border into that area. The cyclone preceding it develops over Texas, Oklahoma, or northern Mexico or moves through that region from the southern Rockies. Yet it is well known that many strong high pressure areas have moved into the former area and numerous energetic cyclones have passed through the latter region without producing severe cold waves on the Texas coast. The two, in combination, cause the cold wave, and their movements must be favorably timed. At any stage in the progress of the high and cold wave, there are unfavorable positions for the LOW and, in those situations, the HIGH either blocks the forward movement of the cyclone and the vigorous circulation of the latter opposes the cold winds of the former, or, the cyclone moves too rapidly, drawing the cold to other regions.

When a strong HIGH is advancing into Montana and western North Dakota, a severe cold wave may set in over the Texas coast within 24 hours provided the low pressure area is favorably situated. It is important, then, that the average movement of southwestern LOWS be accurately known.

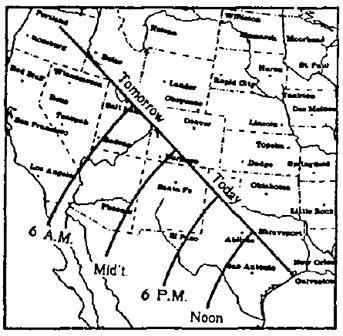

From a study of the movement of 102 southwestern depressions, the chart shown in Figure 1 has been prepared. Using sea-level pressure at New Orleans as a basis of comparison, the hour lines over southwestern States have been drawn. When the pressure along any of these lines equals the pressure at New Orleans, the wind at Galveston will shift to west or north, in an average case, at the hour indicated on the line.

This device has an advantage over the use of the low-pressure center and its average movement, because it takes into account both the location of the center and the pressures exerted upon it.

Pressure indications of severe cold wave

When the cyclone is over the southern Rockies, pressure must be high in the far Northwest. Relatively low pressure in Montana is at this stage indicative of failure to reach the Texas coast.

High pressure in the northern plains normally in 24 hours moves in winter to the upper Mississippi Valley, western Lakes or thereabouts. With the crest of the HIGH in the latter region, a cold wave is not likely. The center of the LOW must then be passing through the west Gulf region or the lower Mississippi Valley, unless pressure continues very high in Montana or shows immediate signs of reinforcement.

When a powerful cold wave is sweeping across the Texas coast, a barometric gradient of about 1 inch usually obtains between the northern plains and the lower Mississippi Valley. Great pressure differences between these regions are essential. Therefore, indications must point to a maintenance of high pressure in the northern plains until the LOW in the southern Rockies has moved eastward or southeastward into the lower Mississippi Valley or thereabouts. Any indications of weakening of this pressure in the north before the LOW passes out point to probable failure of the cold wave.

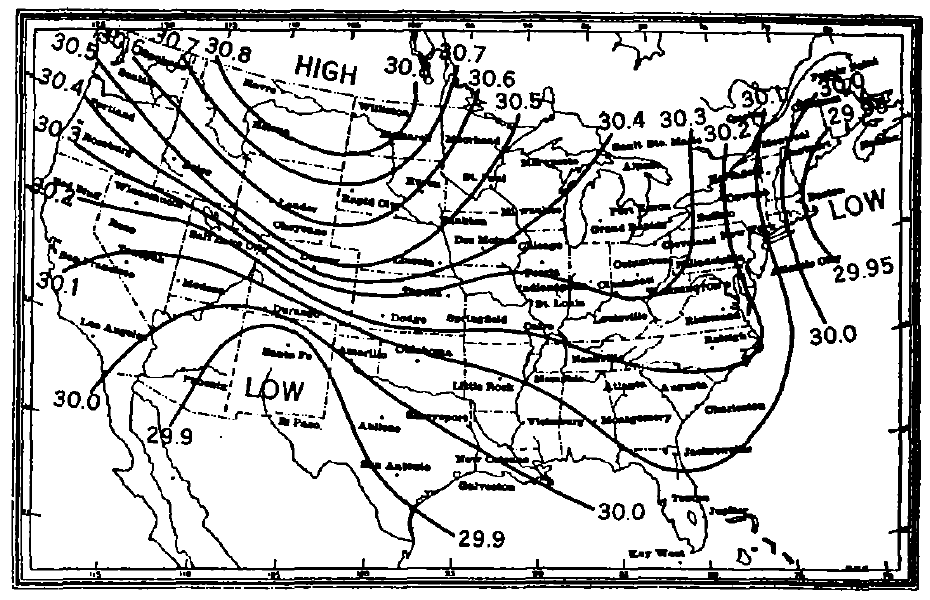

Figure 2 is an isobaric chart, a composite of five, immediately preceding five very severe cold waves reaching the Texas coast, those of 1886,1895,1899,1905, and 1918.

Figure 2 - Average barometric pressures over the United States, 24 hours approximately, preceding a severe cold wave on the Texas coast. Composite of five maps -average minimum temperature at Galveston, 13°

Averages of barometric pressures for representative stations, some interpolated from published charts, were used. Approximately 24 hours later, in each instance, a severe cold wave was in progress. The preceding cyclone, having drawn cold air southward and eastward, is evident in the far Northeast. The second cyclone overlies the southern Rockies and a strong high pressure area is moving southeastward from the British northwest.

All the barometric conditions, necessary for a severe cold wave within 24 hours are amply fulfilled, as follows:

- A powerful pressure gradient from Helena, Mont., to New Orleans, La.

- Pressure at Salt Lake City higher than at New Orleans.

- The general pressure distribution is decidedly favorable to the southeastward movement of the depression through Texas or that immediate vicinity into the lower Mississippi Valley.

- Pressure at Helena higher than at Nashville.

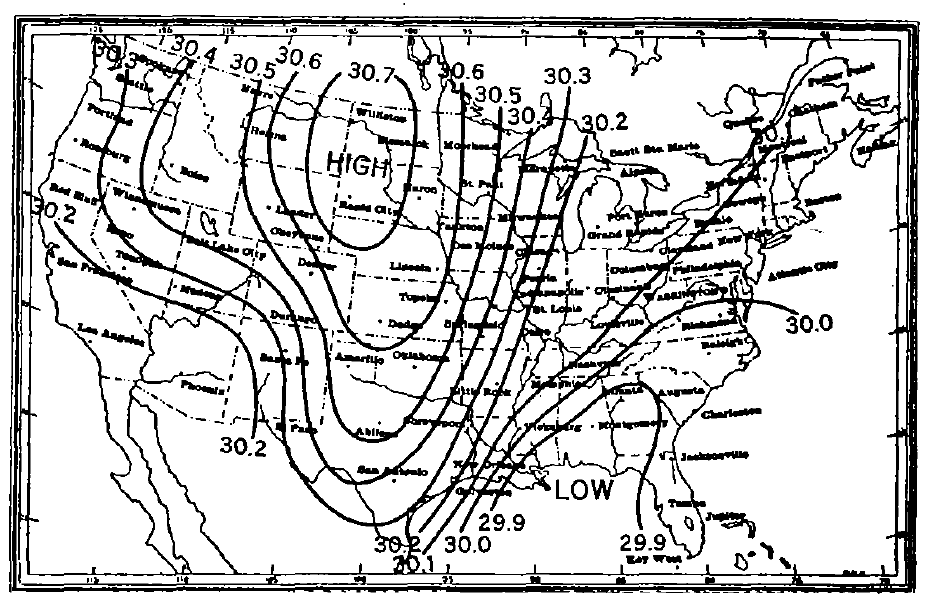

Figure 3 is a composite of the five severe cold waves, 24 hours later, with a gale from the northwest, temperature well below freezing and falling rapidly, wind averaging 34 miles at time of observation and a 12-hour maximum averaging 41 miles per hour.

Figure 3 - Average barometric pressures severe cold wave in progress at Galveston; gale from the north and northwest, rapidly falling temperature. Composite of five maps 24 hours later than that shown in Figure 2

The pressure gradient from North Dakota to southern Louisiana now averages more than 0.80 inch. A powerful indraught of cold takes place through the plains region into West Gulf States. Pressure is relatively high in the Southwest. The crest of the northern HIGH, or center of divergent winds is far to the northward and the cold air is drawn from high latitudes.

In short, the cold wave is produced by high pressure and low temperature in the northern plains and low pressure in the lower Mississippi Valley. Preceding this condition by 24 hours, then, the southwestern LOW must be in a position to pass eastward of the Texas coast and the pressures exerted upon it must be favorable for such a movement. The barometer must be high to the westward of the northern plains region so that high pressure in the latter area will be maintained until the LOW has passed eastward. A well-defined LOW centered in the region about Utah or Nevada is a decidedly unfavorable condition.

It is understood, of course, that barometric tendency at the time of report is to be taken into consideration; in all cases the 12-hour pressure changes should be considered.

CONCLUSIONS

1. Cold waves with temperatures below 20° occur at Galveston about once in 8 years, at Corpus Christi once in 10 years, at Brownsville once in 15 years; below 25° at Galveston once in 2.5 years, at Corpus Christi once in 3 years, at Brownsville once in 3.5 years.

2. In cold waves at Galveston a temperature very near the minimum is reached within 30 hours after the initial steep decline begins.

3. When the cold wave arrives before noon, the first day, the minimum occurs generally on the morning of the second day; when it arrives after noon of the first day the minimum is usually recorded on the morning of the third day.

4. When clear, the minimum comes shortly after sunrise; when cloudy it is delayed until near noon.

5. Twenty-four hours ahead of the cold wave pressure must be high over Montana and a steep gradient between that locality and the lower Mississippi Valley is essential for a marked fall in temperature. HIGHS with center east of 95° west, and south of 40° north produce little change in temperature.

6. When the LOW is centered in the southern Rockies, the time of wind shift on the Texas coast is determined by relative pressures in Utah and southern Louisiana. Oklahoma seems to be about 24 hours distant in time, judged by the average movement of cold waves.

7. When the HIGH is in the northern plains and pressure is relatively low in the northern Rockies, the depression must be in the west Gulf or lower Mississippi Valley and the cold wave must be in progress on the Texas coast or imminent. Otherwise failure is probable.

8. In any case, a well-defined depression in Utah or Nevada is always indicative of failure.

9. When the cold wave is moving southward and at 7 a.m. is well established in the southern plains and threatens the Texas coast, the mean of the 7 a.m. temperatures at Santa Fe and Oklahoma will be 17° lower than Galveston's minimum of the next morning. When not well established in the southern plains at 7 a.m., the cold wave will not arrive at Galveston in 24 hours unless the pressure gradients are abnormally steep and the impending cold wave exceptionally severe.

10. When exceptionally violent the cold wave may reach the Texas coast from Oklahoma in less than 24 hours, in which case the temperature at Oklahoma is not a reliable index. This condition is characterized by excessive temperature differences between North Platteand Oklahoma.

11. When there is a depression in the southern Rockies and the pressure at Helena, Mont., is 0.60 inch or more above that at New Orleans, a cold wave is threatened. Its violence increases with the gradient.

This article has been edited and abridged specifically for the AMS Weather Band. Any omissions or errors may be attributed to AMS Staff.