What Inspired the First European Images of Tornadoes

- By AMS Staff

- Dec 28, 2021

In addition to art, culture, and philosophy, the European Renaissance (1400-1600 CE) brought the first serious attempts to predict the weather and new approaches to forecasting. While the invention of measurement devices such as the thermometer (in 1607) and the barometer (1643) was yet to come, increased interest in weather observations came from the “discoveries” of new lands and seas, which considerably enlarged and widened old ideas and conceptions.

Western explorers found atmospheric phenomena they had never seen before, and climates that were very different from those at home. Among these new meteorological phenomena, tornadoes and waterspouts caused a great deal of interest due to their damaging effects, as well as their beauty.

For centuries, the concept of tornadoes was indistinguishable from other windstorms. The word "tornado" had an archaic meaning concerning variable, gusty winds and rain, and, perhaps, thunderstorms near the equator. The Oxford English Dictionary (1989) defines a tornado in the following way: "In the 16th century navigators called a tornado (or ternado) a violent thunderstorm of the tropical Atlantic, with torrential rain, and often with sudden and violent gusts of wind . . . later on a tornado was defined as a violent storm (now without thunder), affecting a limited area, in which the wind is constantly changing its direction or rotating."

The definition, including the thunderstorm, was used for the first time in 1556, whereas the thunder-free definition was applied later beginning in 1625. The first edition of Encyclopaedia Brittanica, published in 1771, defined a tornado as "a sudden and vehement gust of wind from all points of the compass, frequent on the coast of Guinea." The term "tornado" originates from various terms, such as "ternado," “tornatho," "trovados," and others. It was not until the 1840s that the Spanish word "tornado" was narrowed in meaning to designate a local rotary storm (Ludlam 1970). Fleming (1990) pointed out that there was still an argument about terminology such as tornado, whirlwind, and hurricane as late as about 1840.

But even before the introduction of the term “tornado,” early records from European authors documented the power of tornadic storms. The Roman encyclopedist Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.) described the menace of whirlwinds to sailors in his "Historia naturalis" (70 A.D.), and also mentioned the waterspout, "that cloud which draweth water to it, as it were into a long pipe" (Heninger 1960). Columbus described a tornado that turned into a waterspout during his second voyage in 1495 (see also Brooks 1941). Also, Machiavelli (1469-1527) described a tornado crossing Tuscany (Machiavelli 1532), and the Portuguese navigator and poet Luiz de Camoes (1524-80) documented poetically a waterspout that was probably observed on the western coast of Africa (Hellmann 1924b). Shakespeare (1564-1616) referenced a waterspout in his play "Troilus and Cressida," as "the dreadful spout, which shipmen do the hurricane call, constringent in mass by the almighty sun." Originally, the tornado-like phenomenon is differently termed in historic texts, for example, Machiavelli used the word "storm." A variety of terms denoting tornadic activity is also evident in the description of early American tornadoes (Ludlam 1970).

But even before the introduction of the term “tornado,” early records from European authors documented the power of tornadic storms. The Roman encyclopedist Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.) described the menace of whirlwinds to sailors in his "Historia naturalis" (70 A.D.), and also mentioned the waterspout, "that cloud which draweth water to it, as it were into a long pipe" (Heninger 1960). Columbus described a tornado that turned into a waterspout during his second voyage in 1495 (see also Brooks 1941). Also, Machiavelli (1469-1527) described a tornado crossing Tuscany (Machiavelli 1532), and the Portuguese navigator and poet Luiz de Camoes (1524-80) documented poetically a waterspout that was probably observed on the western coast of Africa (Hellmann 1924b). Shakespeare (1564-1616) referenced a waterspout in his play "Troilus and Cressida," as "the dreadful spout, which shipmen do the hurricane call, constringent in mass by the almighty sun." Originally, the tornado-like phenomenon is differently termed in historic texts, for example, Machiavelli used the word "storm." A variety of terms denoting tornadic activity is also evident in the description of early American tornadoes (Ludlam 1970).

Wegener (1917) identified this illustration of a tornado of 1587 as being the first tornado drawing ever done in Germany, and he assumed that it was probably the first worldwide. But this was not the first artistic image of a tornado that we have on record.

Wegener (1917) identified this illustration of a tornado of 1587 as being the first tornado drawing ever done in Germany, and he assumed that it was probably the first worldwide. But this was not the first artistic image of a tornado that we have on record.

A series of 12 tapestries called the "Conquest of Tunis," were made for the emperor Charles V, in which both a tornado and sandstorm are depicted. In 1535, he undertook a crusade to Tunis against the Ottoman emperor's power in the western Mediterranean region. In order to ensure that the expedition would not be forgotten, Charles V brought along poets, musicians, mathematicians, astrologers, and the Flemish painter Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen (1500-59). Vermeyen painted sketches depicting important scenes of the crusade to be used as prototypes for the tapestry series "Conquest of Tunis," later woven in Brussels by the carpet manufacturer Willem de Pannemaker.

The sixteenth century is characterized by a strong contrast between Christendom and Islam, with a long boundary running from the Balkans through the Mediterranean region. As both sides sought to increase power, economic, and religious advantages through war, there were a number of confrontations, including one in 1535.

A corsair named Barbarossa had been commissioned as admiral of the sea by the Ottoman emperor and was active in disturbing the growing flow of trade goods and merchants in the western Mediterranean Sea. This pirate had become a serious menace to European powers by 1529, when he seized the ports of Algiers as a base of operations. Therefore, in 1535 Charles V undertook a "holy crusade," as it was termed by the emperor, against Barbarossa in Tunis in order to free some 20,000 captives, and reduce Ottoman power in the region. Not only did he invite painters such as Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen to join the emperor's army and celebrate the military campaign began in Tunis, but in 1548 the carpet manufacturer Willem de Pannemaker was entrusted by the emperor's sister Mary with the production of tapestries based on the painter’s work. In 1554 the series of tapestries "Conquest of Tunis" were successfully finished and were considered to be one of the most important pieces of court art of the Habsburgian emperor Charles V. The series is a major monument of military commemorative art.

Tornado in the Mediterranean

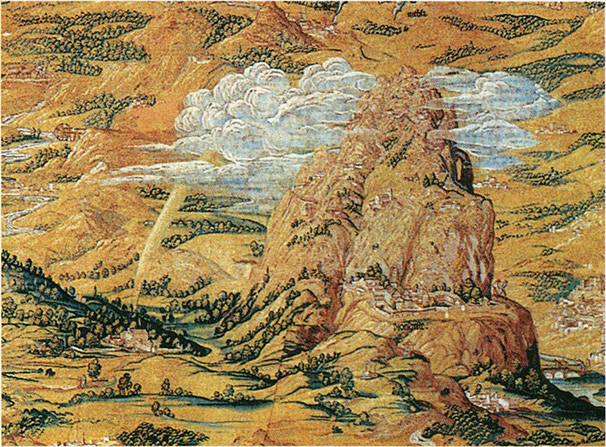

This tapestry, begun in May 1549, was reviewed and approved by the Brussels guild of tapestry weavers in spring 1551. Showing the western Mediterranean basin in the form of a portolan map, the tapestry served to introduce pictorially the dramatic history of the Tunis expedition by presenting the related geographic and strategic areas. North Africa is seen at the top of the map and southern Europe at the bottom; Spain is at the lower right, and Italy is at the lower left. The north-south orientation, which is the reverse of present-day cartographic practice, was at that time the usual practice for mapping Europe.

In addition to Tunis, we also see Naples, Rome, and Genoa, Italy; Marseilles, France; Barcelona, and Malaga, Spain; and Lisbon, Portugal, in a bird's-eye view. Horn (1989) indicated that Vermeyen used this view because he might have seen the famous painting by Albrecht Altdorfer, "The Battle near Issus" (1529), in Munich in 1530, which shows the same perspective.

Most coastlines and locations of the ports are correctly located geographically. But the ports themselves and the ships are overly large in comparison to the rest of the map because Vermeyen deliberately sacrificed accuracy for readability.

A further schematic modification appears above the Iberian Peninsula. The isolated mountain on the tapestry is Montserrat, which is at a distance of about 50 km west of Barcelona. This means that the entire Iberian Peninsula, which measures more than 800 km both in the zonal and meridional direction, is geographically concentrated in the area of Barcelona and its closer environment. The presence of Charles V in Barcelona and his visit to the Montserrat monastery before the embarkation of the Spanish fleet toward Tunis provide a reason for this concentration. Horn (1989) speculates that Montserrat was rendered so centrally and largely because of its religious significance for the emperor.

Enlarged portion of the first tapestry shows the tornado near Montserrat mountain. Image courtesy of Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid.

But one of the most striking features on the first tapestry is a tornado shown above the Iberian Peninsula. The enlarged image here shows a tornado close to Montserrat leaving a cloud and touching the ground. The cloud resembles a fair-weather cumulus rather than a dark cumulonimbus. The funnel narrows with decreasing height and is very slim where it touches the ground. Clearly, Vermeyen must have seen at least once a funnel cloud, which might have impressed him by its strange and elegant shape. This might have led him to concentrate exclusively on the funnel detail and, therefore, he combined the slender funnel with fair-weather clouds. A further interesting detail appears in the image below, another enlarged portion of the tapestry which depicts an area of heavy rain located south of Tunis close to the mountains. A similar scene showing an extended curtain of rain wisps can be found in the background of the fourth tapestry "Skirmishes on the Cape of Carthage".

To interpret the weather features that appear one could investigate whether the depicted weather was observed by Vermeyen (and by Charles V) in the corresponding region during the period of the expedition. Contemporary accounts of the expedition to Tunis are plentiful. Virtually every step Charles V ever took drew the attention of the historians of his time, and any major campaign, such as his conquest of Tunis, attracted a whole spate of publications. As a matter of fact, however, a search through literature on Charles V reveals few references to any kind of weather. In the collection of Charles V's letters (Fernandez Alvarez 1973) there are various references to weather, for example, "buen tiempo," "fresco," and "fait o de viento," but there is neither a report on a tornado nor heavy rain. The original version of the diary of Charles V, the "memoirs," has been lost, and the only surviving copy is one dated 1620, written in Portuguese. A modern Spanish translation is provided by Cadenas y Vicent (1989) in which there is no mention of special weather related to Charles' crusade, except for a sandstorm occurring close to Tunis and a disastrous storm that occurred during the Algiers campaign (a later expedition to Africa in 1541 in which the emperor lost most of his naval fleet).

To interpret the weather features that appear one could investigate whether the depicted weather was observed by Vermeyen (and by Charles V) in the corresponding region during the period of the expedition. Contemporary accounts of the expedition to Tunis are plentiful. Virtually every step Charles V ever took drew the attention of the historians of his time, and any major campaign, such as his conquest of Tunis, attracted a whole spate of publications. As a matter of fact, however, a search through literature on Charles V reveals few references to any kind of weather. In the collection of Charles V's letters (Fernandez Alvarez 1973) there are various references to weather, for example, "buen tiempo," "fresco," and "fait o de viento," but there is neither a report on a tornado nor heavy rain. The original version of the diary of Charles V, the "memoirs," has been lost, and the only surviving copy is one dated 1620, written in Portuguese. A modern Spanish translation is provided by Cadenas y Vicent (1989) in which there is no mention of special weather related to Charles' crusade, except for a sandstorm occurring close to Tunis and a disastrous storm that occurred during the Algiers campaign (a later expedition to Africa in 1541 in which the emperor lost most of his naval fleet).

To sum up, with the exception of the sandstorm, the depicted weather features do not show a documented event, as is the case of the tornado that is observed at a defined place and time around Montserrat mountain. It is likely that weather features were used as decorative or symbolic objects in order to improve the general aesthetic appearance of the piece of art and to support the transmission of religious or political ideas. That the tornado is located so prominently in the tapestry's center and is so dominant in structure that the eye is drawn to it perhaps emphasizes its symbolic texture.

The Importance of the Tapestries

During the first half of the sixteenth century, tapestries were the obligatory fixture of a European court and were used as an instrument for political propaganda and dynastic demonstration. The tapestries of the "Conquest of Tunis" series are large, with a mean height of about 13 feet and a width of 23-40 feet. Few rooms would have been large enough to allow for the entire series to hang at once because it covered a wall at a length of more than 300 feet. In combination, the 12 huge tapestries displayed in one vast and rich chamber must have looked grandiose, almost overwhelming. Therefore, they were used to decorate festivity halls for longer periods of time. Normally, such huge tapestries were hung on the outside walls of buildings. The first prominent opportunity to show the series was the marriage of Philippe II—the emperor's son—to the Queen Mary Tudor in Winchester Cathedral on 25 July 1554. The tapestries accompanied the emperor in all of his travels throughout Europe, and when he retired in Yuste, he brought the tapestries with him. Ever since, they have remained in Spain.

For a constantly traveling emperor, such as Charles V, these tapestries were convenient because they were easier to transport than paintings of a similar size. Another reason was the very striking aesthetic effect of tapestries. A further advantage of the tapestries was the possibility of reproducing them mechanically; thus, the same depiction (and propaganda) could be presented simultaneously in different places. Taking into account the significant expense and the great effort that were required to move these tapestries, one can guess how important they were. Also, the production costs of the prepatory designs and the series of tapestries were enormous, around 33,000 Flemish pounds. This amounts to about 160,000 Gulden, or about 9,000,000 pounds Sterling in 1903 (Van Ysselsteyn 1969). When one considers that Charles V raised the necessary funds while he continually hovered on the verge of bankruptcy, there can remain no doubt that the "Conquest of Tunis" tapestry series was of immense importance to him. It was his ambition to be recognized as the leader of Christendom, and he viewed his Tunis expedition as a demonstration of his role in history. The original series consisted of 12 design drawings and tapestries; today, 10 of each still exist. The first scene of the "Conquest of Tunis" series has survived only in tapestry form.

This Renaissance depiction of a tornado on Charles V’s tapestries is one of the earliest images of a tornado known in Europe. Art from other continents may contain depictions of tornadoes long before the sixteenth century. The tornado appears on the first tapestry of the "Conquest of Tunis" series that was woven between 1549 and 1551; the same tapestry also shows a heavy rain shower. Furthermore, a similar heavy rain shower and a sandstorm are depicted in the fourth tapestry of the series. The original model for these tapestries, painted by Vermeyen, was finished several years earlier. The artistic depiction of the tornado is a highly unique feature, considering the contemporary variety of meteorological phenomena appearing in tapestries and wall paintings of the Italian High Renaissance between 1510 and 1600. A literature search indicates that the depicted weather phenomena, except the sandstorm, were not recorded during the crusade to Tunis.

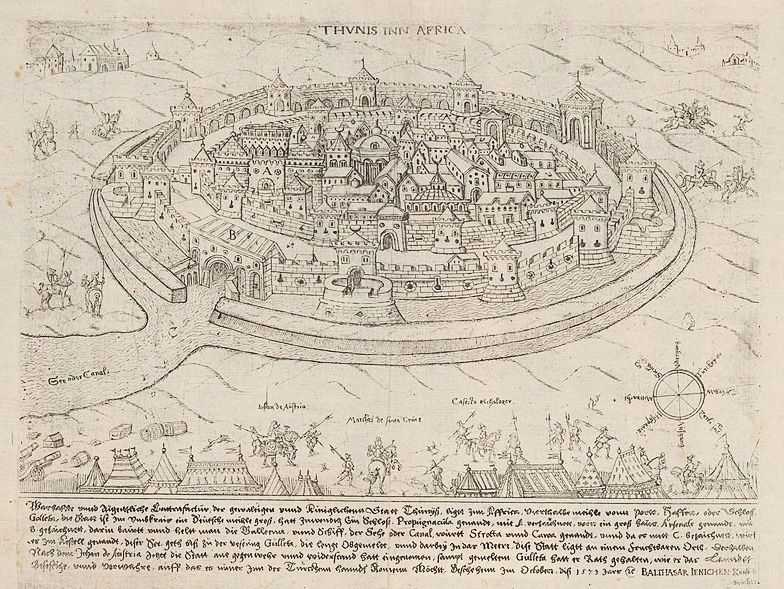

A map of Tunis from 1573, showing a highly stylized geography.

The details of the tapestry show that the depiction of nature is complicated in the paintings, as well as in other pieces of art of the sixteenth century, because it combines naturalistic parts or details in an unrealistic manner. These details could be of a narrative, emblematic, and even schematic character. It can be concluded that in very few cases the paintings are an exact documentation of nature, but they are, in general, a balanced representation between the description of facts on the one hand and free intervention on the other. The artist acted as the creator of plausible fictions. The question of fiction, invention of nature, and nature in pieces of art has to be answered with the following paradox: the artists invented their art naturalistically. At that time the artist's aim was to use the characteristic elements of the landscape, including weather features, and to link them to symbolic ideas.

On the other hand, the depiction of landscapes and weather for its own sake started at the same time (see, e.g., the sketches of Albrecht Durer). But it was not until the seventeenth century that painting the sky and landscapes became fashionable. With regard to art history there is a shift from the textual narrative representation in Renaissance Italy, to the visual descriptive depiction in Dutch seventeenth-century painting between the early and late Renaissance period. The painter Vermeyen, with his "Conquest of Tunis" series stands in a very interesting juncture in art history—somewhat between these two chronologically, geographically, and in the form of representation. The "Conquest of Tunis'' series gives a reliable and complete account of the campaign and represents official history, narrated in the captions and depictions of the tapestries. One must not look to them, or the other written accounts of the expedition, for modern, critical history writing, but for an official version of what happened, along with emblematic puzzles.