My Father and the Conrad Holmboe Expedition to Greenland in Summer 1923

- By Thomas Rossby

- Jul 1, 2023

Map with track of the Conrad Holmboe

On a bright spring Sunday in 1953 when I was home from boarding school my father and I were walking along the harbor front in Stockholm. To our right was the Royal Palace, to our left the Grand Hotel, and straight ahead on Skeppsholmen, an island in the harbor, the full-rigged steel ship af Chapman, a vessel I later learned he had sailed on twice. But then he said something curious, that he had been on an expedition to Greenland in summer 1923 – 30 years earlier. Curious, because it came as a complete surprise to me. I had always seen my father dressed in a dark business suit with matching coat, vest, and pants, ironed white shirt, and the crooked tie my mother liked to straighten out, not as someone who had experienced the rough and tumble of life at sea. To me he was a complete loss around the house, he might be able to replace a light bulb, but prepare a meal or use a screwdriver, forget it. Mother did all the driving the few years we had a car.

The objective of the expedition was to relieve the men at a weather station Norway had established at 74°N on the east coast of Greenland the year before. It was the most recent of several stations that Norway had established to improve weather coverage around the Greenland and Norwegian Seas, the others being on Jan Mayen, Svalbard and Bear Island. It wouldn’t surprise me if the Bergen school on frontal dynamics had some influence on the development of these plans. My father had spent a year in Bergen several years earlier so perhaps he wanted to be part of the action – he was a guest meteorologist onboard.

I don’t recall his exact words that spring Sunday, but he mentioned that the expedition did not go well, they were not able to reach the men on Greenland due to the crushing ice that summer. As I read in the book Grønland (more about this later), they had a very difficult time battling the ice and for quite a while they had to store their gear on an ice floe for fear of the ship suddenly being crushed. You might think this would put an end to an impractical young man’s sea going, but he evidently had an adventurous mind for the following summer he joined the af Chapman (the cadet ship of the Royal Swedish Navy) as a meteorologist on its cruise around the British Isles and in summer 1925 when they sailed to Portugal and Madeira. I’m sure I asked him some questions about the expedition, but my lasting impression seems to be that he didn’t want to talk about it, and I don’t recall learning anything more.

Fast forward to 2018 when I was visiting the Meteorological Institute at Stockholm University. One day my colleague Prof. Peter Lundberg gave me a photocopy of a chapter from a book titled ‘Grønland’ by the Norwegian polar Explorer Gunnar Isachsen, published in 1925. The chapter titled ‘Conrad Holmboe’s drift in the Greenland ice 1923. A first account describes in considerable detail the July 19 to October 11 voyage from Tromsø, Norway to Isafjord, Iceland. It is possible I saw the book in father’s library, but he never mentioned anything about it. He wouldn’t have, looking back I am struck by how rarely if ever he would reminisce about the past. I know next to nothing about his childhood, upbringing or life in a city apartment with three brothers and a baby sister by the time he graduated from high school. My Swedish cousins know just as little about their parents. Perhaps that was typical of earlier generations, and perhaps, as a teenager I wasn’t very curious about his early life.

Spanning 46 pages, the full account of the expedition in the Grønland book is far too long to be reproduced here, but the chapter starts with an excellent 3-page summary which I have translated below. It gives the reader a good idea of what they hoped to achieve and had to endure for the two months they were stuck in the ice. In the best sense of the word it is a chilling story. For the interested reader I have translated the full diary, describing in considerable detail the reasons for the expedition, their stop at Jan Mayen Island and their two-month ordeal coping with the ice as they drifted south. The diary can be found here: https://web.uri.edu/gso/research/rossby-conrad-holmboes-drift-in-the-greenland ice-1923-a-first-account/. A scientific account of the expedition written by Tor Kvinge (1963) can be found here: https://folk.uib.no/ngfso/Norskehavet/historical/KvingeT63.pdf It includes a tabulation of all weather and oceanographic data collected during the expedition.

I’d like to acknowledge Mr. Ivar Stokkeland, chief librarian at the Norwegian Polar Institute in Tromsø. He provided me with scanned copies of the diary photographs. The diary mentions that my father made film recordings of polar bears, and no doubt of other activities on board. Mr. Stokkeland found a note in the Norwegian daily Aftenposten that my father reported on the expedition only a month later in Tromsø. He also showed his movies. Mr. Stokkeland and I have searched in all libraries and national archives across Norway and Sweden for those films, but without luck. (I’m tempted to say this was typical of my father, he was not one to keep stuff lying around, perhaps reflecting his somewhat restless style.) Mr. Stokkeland also helped me with words and phrases I could not find in the dictionaries. Having said that I take full responsibility for any errors of translation. Photos courtesy the Norwegian Polar Institute, Tromsø, Norway. I encourage you to visit: https://bildearkiv.npolar.no/fotoweb and search for Conrad Holmboe.

Reference: Isachsen, Gunnar, 1925. Grønland og Grønlandsisen. J. W. Cappelens Forlag, Oslo, 248 pages.

Conrad Holmboe’s drift in the Greenland Ice 1923

A first account

(Translated from the Norwegian by T. Rossby)

Seydisfjord, 17 October

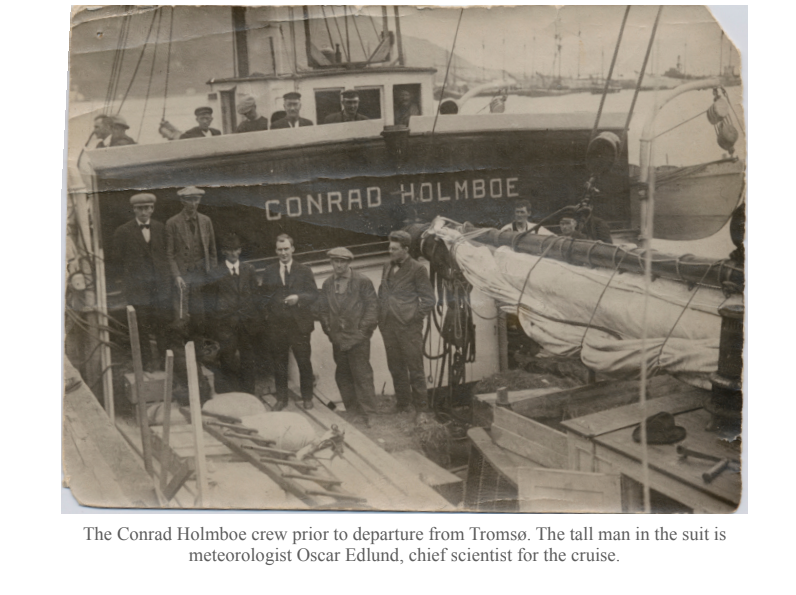

The expedition with the motorboat “Conrad Holmboe” was sent out by the Geofysiske Institutt in Tromsø. The chief scientist of the expedition was the director of the weather forecasting office in Tromsø, Mr. Edlund.

After having dropped off oceanographer Mosby and three men to relieve the radio operators on Jan Mayen, and who later returned home on another vessel, we went at the end of July north and west along 74°N. Onboard besides the crew were four hunters and a radio operator to relieve captain Johan Olsen and his six men at our radio station at Myggbukta on the East Greenland coast at 73½ °N. In addition, the Swedish meteorologist Rossby and I were invited to take part in the expedition. All in all we were 16 men onboard.

Meteorologist Carl-Gustaf Rossby, oceanographer Olav Mosby, and mate Johannes Jensen

Last year the polar current transported little ice, this year much more due to easterly winds all summer which pushed toward land a band of ice around 80 km wide at 74°N with virtually no opening toward the coast.

On August 2 we became trapped at 74 ¼ °N and drifted hither and dither southward in the ice at various rates for more than two months. In the beginning the drift was fairly steady without ice pressure. But on the 28th of August the sun and the quiet disappeared. Gales broke up the new ice and big floes pressed together and huge ridges of ice towered around us. The floes fractured, the boat was thrusted up, at turns at the bow and the stern. At times the squeezing got quite violent. The deck load with supplies for housing on Greenland had to be jettisoned to lighten the vessel. Equipment, provisions and whaleboats were offloaded onto the ice.

On the 7th of September the weather service in Bergen telegraphed via Jan Mayen that there was danger for a sudden storm in the afternoon. It came the following day, the 8th. The intense ice pressure led to serious leakage both fore and aft of the hull. The fate of the ship seemed decided.

While we were busy throwing everything on the ice, a lead opened up between the floes. Even though the rudder handle was broken we hastened over to another floe some hundred meters away. The five men who didn’t make it onboard from the floe where we had our things, worked to bring everything together as this floe broke into several pieces shortly after we left them. They were later brought onboard.

The storm increased during the pitch-dark night and the sleet didn’t leave a dry thread on our frozen bodies. We had to secure ourselves to the new floe, but the storm and ice pressure kept ripping the lines. Broken and uneven ice, floes and high ridges made for a witch dance around us. The pumps were at it nonstop.

Even though the boat survived the rage during the night, it was with apprehension we faced the next day. Where was the floe with our gear, provisions and the three dories? For a brief moment Sunday morning we sighted land. We were in the middle of Davy Sound at 71°47’N and our supply floe had been kind enough to keep itself at an easy distance. Pumps were constantly at work and any free hands were busy straightening out the mess. A line caught in the propeller was also removed.

We continued drifting south along the Liverpool coast about 5 nautical miles (NM) from land. Even if we had wanted to it would have been hazardous to reach land in the boats through the new ice and the meter thick soup between the floes.

The thrusting and ridging continued at all hours of the day.

Ice ridge from the Conrad Holmboe

On September 30 we were only 1 NM from land, Cape Swainson on the north side of Scoresby Sound, but a northwest gale put us the next day in the middle of the fjord entrance. If the vessel had been wrecked on land during the night would have meant safe

survival, but stuck for the winter. Firmly hoping that we could handle the rest meant that I readily took the risk of continuing to drift.

We danced willy-nilly with our floe southward. The drift went faster, but troubles of all kinds continued to follow us. Toward the end we drifted 30 NM per day. Our floe, which to begin with was one of the smaller ones, had now become one of the biggest. This far south the floes were broken up and had their sharp edges worn away. Big ridges piled up along the edges.

October 3 became a day to remember. In short time we tore down the big tent, Villa Liverpool we had erected on the floe, and brought everything onboard. We moved 15 NM km that day about 6 NM km from ice edge. We then continued in frozen slurry ice until October 10. When the ice broke up we called the rescue ship ‘Polarulv’ by radio. It was evident and obvious that breaking through the ice edge where the heaving was substantial had to be done today. The hull got what it could take and when dusk came we were out in open water at 67½ °N and 25°W.

We were concerned about how well the ship would cope in the open sea and we found out. In the company of ‘Polarulv’ we set course for the nearest harbor, Isafjord, Iceland. Fast it went with a northerly wind and high seas. At 2 AM in the night the pump started acting up, but now and then it continued to assist. It was a heavy sea. The sails helped a bit, but the reefed mainsail had to be taken down as the gaffe broke off. On October 11 around midnight we anchored in Isafjord.

Since the end of August until now we haven’t had a quiet moment. It has been a rare test of both nerves and muscles. In that sense we shall not complain for lack of boring times or lack of things to do.

The ship suffered serious damage. The outer hull (an extra protective layer of wood) is gone, and main keel is broken in two places. There are also serious leaks. The hull planks have been pushed in and out and several frames are probably broken. The hull sounded like a squeaky organ in the seas. That the ‘Conrad Holmboe’ now beached in Isafjord says something about what a ship can take and what people can accomplish when they fight for their lives.

The 7 men in Myggbukta left with their boat ‘Anni’ on their way home before we drifted by their place. They were on our minds all the time, constantly looking for them as well as the Danish boat ‘Teddy’, which still hasn’t turned back from the Greenland ice. If we don’t hear from the missing soon, we must hope that they got ashore and camp until next year. ‘Polarulv’ is now scanning ice edge from 64°N northward to Jan Mayen.

Gunnar Isachsen

Addendum (T. Rossby): A few days after our arrival ‘Polarulv’ left Isafjord to resume the search for ‘Anni’. Only a few days out, she capsized with three men lost in the heavy seas. She righted herself and drifted helplessly for 30 hours until they were spotted by a British trawler and towed to Reykjavik. In time it became clear that ‘Anni’ with all men was lost. This was no doubt the reason my father said things didn’t go well. The men on ‘Teddy’ made it to Angmagssalik where they overwintered. It was a tough year. (The North Atlantic Oscillation was in a very positive phase.) As Isachsen wrote a few pages later in the book: The ‘Conrad Holmboe’ and ‘Polarulv’ had capable crews of which we have many along our long ocean coast, and ‘in the sweat of work Norway proves its mettle’.