How to Monitor Drought and Build Community in the Desert Southwest

- By AMS Staff

- Dec 8, 2021

As billion dollar disasters continue to take place across the United States, communities are racing to increase their mitigation and response planning for these events. But some are more difficult to plan for than others. Drought in particular can be difficult to get good measurements and data for. It can also have impacts on community life and economic activity that are difficult to separate out from other events.

But drought has become a major feature of life in the southwestern United States. The first decade of the twenty-first century was the warmest, had the second-largest extent of drought by area, and was the fourth driest in the 1901–2010 instrumental record (Hoerling et al. 2013). Research indicates that the overall warming trend across the Southwest is likely to lead to more frequent, more intense, and longer-lasting droughts in the Colorado basin (Gershunov et al. 2013).

Central features of a drought plan are an agreed upon set of drought indicators and a strategy to monitor. Monitoring and routine communication of that information are critical for decision makers to plan for, and not just respond to drought. But good drought indicators and data that is sufficient for decision making purposes is often not available for planners in the western United States. The absence of indicators and data at the right scale is especially acute for Native American communities in the semiarid U.S. Southwest, where instrumental climate data are sparse and dry conditions are the norm.

Recognizing the current limits on effective drought planning, the University of Arizona (UA) and the Hopi Tribe Department of Natural Resources (HDNR) worked to develop a local drought information system that is responsive to the climate-relevant decisions of tribal leaders and citizens. The project addresses three local problems related to planning for and responding to drought: 1) Hopi reservation lands are poorly monitored (instrumentally) for weather and climate; 2) the existing Hopi drought plan relies on indicators and data that are mismatched in scale and scope to the actual experience of drought in Hopi communities; and 3) on the Hopi reservation there is currently no reliable source for local information about drought conditions.

Hopi governance

The Hopi tribe is a sovereign, federally recognized Native American community whose lands are on the Colorado Plateau in northeastern Arizona. According to the 2010 census, the current population of the reservation is approximately 7200 (Arizona Rural Policy Institute 2016). The tribe is a confederation of 12 semiautonomous villages with a central government. The governance in place at Hopi is complex, and the HDNR is an agency of the central tribal government and therefore not directly connected to village governance. One aim of the drought information system is to increase engagement between the HDNR and the villages about drought conditions.

Physical geography

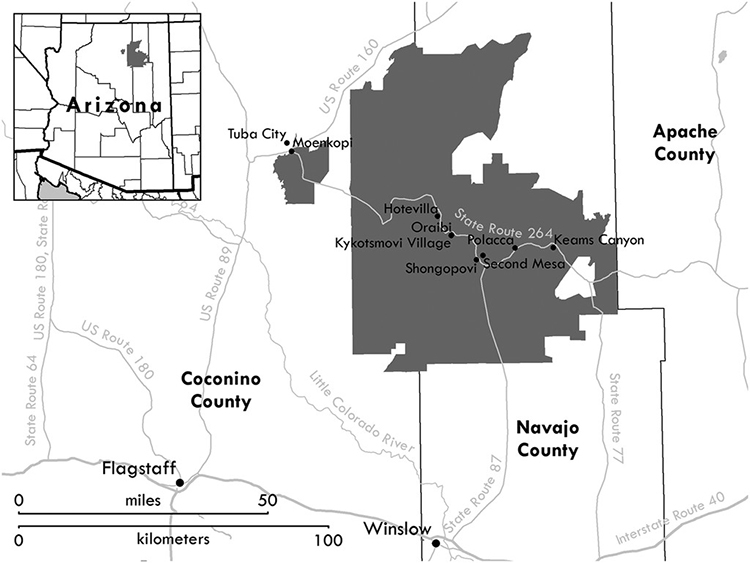

The reservation covers approximately 2,500 square miles in two parcels: the main reservation is made up of three mesas and surrounding lands and the Moenkopi District, which is approximately 40 miles west of the main reservation near the town of Tuba City, Arizona (Suderman and Loma’omvaya 2001). Reservation lands range from approximately 4500 to 7500 feet above sea level. The climate of the reservation is typical of the high deserts in the Southwest. Average annual rainfall across the whole reservation is approximately 8.5 inches, with higher-elevation areas typically receiving more and lower-elevation areas receiving less. Temperatures also vary with topography and throughout the year, but the annual average high temperature for the reservation is about 68°F, with an annual average low temperature of about 37°F. The instrumental record for the region shows that droughts were common over the past 120 years, with a pronounced drought at the end of the nineteenth century and severe drought in the 1950s and early 1960s and again in the late 1990s through to the end of the record in 2015.

Land use

The 2012 U.S. Census of Agriculture shows the entire 1.6-million-ac. Hopi reservation as farmland, with the vast majority of that being rangelands and only 1688 ac. in cropland (National Agricultural Statistics Service 2014). Hopi farming is composed of small family fields—typically less than 10 acres—that are almost entirely rain fed (Singletary et al. 2014, 9–13). Of the 1688 acres that are cropland, only 279 acres are designated as irrigated (National Agricultural Statistics Service 2014).

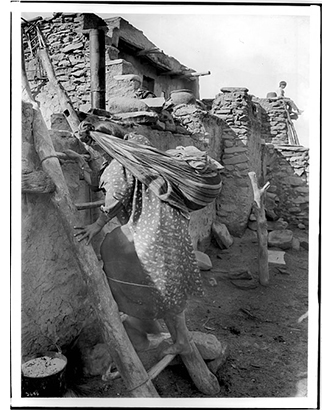

The Hopi have lived on and around current reservation lands for at least a millennium (Sekaquaptewa 2008, p. 27; Singletary et al. 2014, p. 16) and are descended from populations dependent on maize agriculture since at least AD 700 (Adams 1979, p. 285). The terraced fields near the Hopi village of Bacavi are believed to have been farmed since at least AD 1200 (Wall and Masayesva 2004, p. 437). Dryland farming, which is central to Hopi life, is rooted in their origins in this world, with corn described as “the soul of the Hopi people” (Singletary et al. 2014, p. 1). Corn is crucial to Hopi ceremonial life, but it is also a practical part of modern Hopi diet and social life. Cultivars of corn are highly adapted to the semiarid climate of the region. As Wall and Masayesva (2004, p. 440) note, “seeds used now to plant blue, red, white, and yellow Hopi corn arise from a lineage that reaches back for many centuries.”

The Hopi have lived on and around current reservation lands for at least a millennium (Sekaquaptewa 2008, p. 27; Singletary et al. 2014, p. 16) and are descended from populations dependent on maize agriculture since at least AD 700 (Adams 1979, p. 285). The terraced fields near the Hopi village of Bacavi are believed to have been farmed since at least AD 1200 (Wall and Masayesva 2004, p. 437). Dryland farming, which is central to Hopi life, is rooted in their origins in this world, with corn described as “the soul of the Hopi people” (Singletary et al. 2014, p. 1). Corn is crucial to Hopi ceremonial life, but it is also a practical part of modern Hopi diet and social life. Cultivars of corn are highly adapted to the semiarid climate of the region. As Wall and Masayesva (2004, p. 440) note, “seeds used now to plant blue, red, white, and yellow Hopi corn arise from a lineage that reaches back for many centuries.”

Livestock was introduced to the region with the Spanish in the sixteenth century (Pavao-Zuckerman and Reitz 2006); sheep were the primary stock for approximately 350 years. In the early twentieth century cattle began to dominate Hopi ranching. In the 1930s the BIA encouraged and supported ranching by digging wells, installing windmills, and building surface water impoundments across the reservation for watering livestock (Singletary et al. 2014, p. 22).

Consumptive water on the reservation comes almost entirely from subsurface aquifers (Suderman and Loma’omvaya 2001, 30–37). Although current per capita water use on the reservation is estimated to be only 37 gallons per day, there is concern on the reservation that population increases, higher water consumption by modern houses, and commercial development will increase that rate enough that consumptive use will outstrip reliable supply by the mid-twenty-first century (Suderman and Loma’omvaya 2001, p. 33). Impounded surface water is currently used only for watering livestock (from precipitation captured in earthen dams) and for irrigating small farm plots near the village of Moenkopi. But the loss of surface water due to drought conditions does impact Hopi groundwater supplies. To ensure reliable water for future generations, the tribe has been negotiating a claim to the Little Colorado River for decades, but a contentious settlement tentatively agreed to by all the parties in 2012 failed to be passed by the U.S. Congress in 2012 (Lee 2013, p. 643).

Through our interviews with community drought stakeholders, we gathered information about impacts that people were directly attributing to drought as well as many secondary or tertiary impacts. Our goal was to understand how drought was experienced so we could develop an information system that allowed for ongoing community dialogue about conditions that can contribute to a more community-based planning effort.

1) Ranching

The primary drought impacts reported by ranchers are obvious: loss of forage, increased soil erosion, and loss of surface water developed for livestock. We also found two less obvious, but socially important, ways that drought impacts on ranching affect Hopi society more broadly. First, one of the most common responses to drought was hauling water for livestock on the ranges. This occurred because surface water impoundments normally filled by rain were empty. Water hauling as a drought response is costly for the rancher (in terms of fuel and time) as well as the tribal government and community water systems. It strains both groundwater resources and the infrastructure that supports them (i.e., windmills and well pumps). Second, we found that the loss of surface water for livestock has spurred local conflicts. As one HDNR land manager told us, “I noticed every year about June or July we fight over water—everyone wants to protect their own distribution area, but people go out in the middle of the night and take water.” The HDNR and Hopi Police have frequently responded to complaints of neighboring Navajo ranchers filling their water tanks at Hopi wells.

2) Farming

The most common drought impacts on farming and gardening we recorded were reduced crop yield or crop failure. Other impacts included poor soil conditions, and issues with wildlife entering cultivated fields or gardens that were attributed to drought. In addition to direct impacts, we found that farmers in particular discussed drought impacts on Hopi culture. These ranged from simply not having enough crops for ceremonial purposes to a creeping sense of cultural apathy as some Hopi farmers perceive the persistent drought as a failure of Hopi traditions meant to bring precipitation. We also found concern about loss of transmission of cultural knowledge that would usually come from multiple generations working in the fields together. One farmer discussed his concern about losing local corn cultivars, as repeated crop losses have reduced local strains passed down through Hopi families for generations.

Corn field; Hopi Reservation, Arizona, U.S.A. Photo by LBM, C.C. 4.0

3) Ecosystems

Many of the concerns about how ecosystems are impacted by drought closely relate to the ranching and farming concerns described above (e.g., increasing erosion, loss of surface water, decreased vegetation). We also found some concern that loss of surface water and vegetation across the reservation is responsible for declining numbers of prey, in particular fewer rodents for eagles (an important cultural resource). There is also concern about reduced abundance of culturally important plant species used for food, medicines, ceremonies, and crafts. Increased abundance of invasive plant species is also perceived to have come about since the beginning of the current drought. Finally, both farmers and HDNR staff reported an increase in the number of wildlife trespass incidents, particularly in farm fields and gardens.

4) Water Resources

Although potable water supplies for the villages are drawn from deep aquifers that are not tightly coupled with seasonal or annual precipitation, there are water resources challenges associated with drought on the reservation. Across the landscape, springs have historically been abundant and reliable. Interviewees expressed concern that the drying of springs—particularly those that have been used by villages for generations—over the last two decades is tied to drought conditions. There is considerable political debate about the impact that an economically important local coal mine’s use of groundwater is having on springs. Groundwater is closely monitored for impacts from the mine, though those data are contested, so it is difficult to assess exactly what is driving the drying of springs. Less contentious is the relationship between some historically reliable seeps and springs that are tied to shallow aquifers and unlikely to be impacted by groundwater pumping. There have also been impacts on farming, as some ephemeral washes on the reservation have remained dry for multiple seasons. These alluvial plains have historically been ideal farm lands because periodic flows deliver nutrients and relatively high soil moisture.

Drought decision-making

At the scale of the tribal government, drought decisions are limited to a few possible actions, but they have the potential for substantial impact on Hopi people now and in the future. The tribe periodically restricts open fires when conditions are dry. They can also reduce the number of livestock on the ranges, and completely close ranges and restore them if the conditions warrant such action. The tribe is also working to settle surface water rights so that the Hopi people will have reliable water supplies beyond their current groundwater systems. Additional tribal responsibilities include managing and maintaining infrastructure that is impacted by dry conditions (e.g., windmills and wells, roads that are damaged by blowing sand, fences that are periodically buried by dust storms), all of which can be costly.

In addition to government-level decisions, there are many short-term, drought-related decisions being made at the household scale. Ranchers are almost annually confronted with the difficult decision of whether to divest themselves of livestock, continue to haul food/water, or simply hope for the best and leave their animals to fend for themselves on the ranges. Farmers in our study reported altering their practices by planting earlier, later, or more frequently as soil moisture dictates, reducing field size, or hauling water in extremely dry times in order to provide moisture to individual seedlings.

Although drought decision-making related to farming and ranching in the United States is typically thought of in terms of seeking relief funds from government programs, our research shows that this is negligible on the Hopi reservation. Between 1995 and 2012, Arizona farmers and ranchers received a total of about $94.3 million in USDA disaster payments, primarily from drought. Of that $94.3 million, less than $28,000 went to farmers and ranchers in the Hopi zip code, with the average individual disaster payment being less $200 over the entire 17-yr period.

The Hopi tribe adopted a drought plan in 2000, though we found that it has not been fully implemented. A significant barrier to having the drought plan used operationally is the complex monitoring and trigger system that inspired our HDNR–UA collaboration. The plan, developed by an off-reservation environmental consulting firm, characterizes drought according to conventional climatological definitions: meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological. As the HDNR is currently constituted, there are not sufficient data available to support the monitoring categories and limited ability to handle data, so in practice it is nearly impossible for the tribe to declare drought by following the standards set out in the plan.

Based on the information presented above, we have been working with the HDNR on development and implementation of a drought information system that is capable of communicating drought conditions in local terms, and can enable more communication between the HDNR and Hopi communities. The key elements of this system are that it 1) is based on information that reflects how drought is experienced by Hopi citizens and resource managers, 2) combines local observations of drought impacts (e.g., from agriculture, ecosystems, and culturally important uses of the land) with conventional indicators available locally (e.g. precipitation), 3) brings together local expertise with conventional science-based observations, and 4) is capable of both informing and engaging a wide variety of local drought stakeholders.

Our vision is a local drought information system that incorporates observations that the community feels are relevant to drought status. In practical terms, the first step in developing the system is to routinely collect and synthesize the drought-relevant information from within the HDNR described above and distribute it to drought stakeholders across the reservation. In 2014 we worked with the HDNR to produce and distribute four quarterly Hopi drought summaries. In its initial form, the drought summary was a two-page PDF distributed via e-mail within the Hopi tribal government and to some non-HDNR stakeholders. The first page—produced by the HDNR—presented local information about range conditions and precipitation recorded by rain gauges located on the reservation. The second page—produced by our UA team—contextualizes the local conditions with regional climate data and information, including recent temperature and precipitation data as well as the most recent USDM map. Even in this bare-bones form, this summary of drought conditions was used by the Hopi tribe to inform a decision in late October 2014 to impound some livestock on ranges on a part of the reservation shown to be in poor condition in the July–October 2014 drought summary.

Ideally, this type of drought summary will grow over time to include all the relevant information HDNR technicians already collect, but will also expand to include seasonal reports about crop conditions by farmers, reports from community water systems about water hauling, and any other drought-relevant information the HDNR or villages choose to routinely contribute. Our work so far suggests that there are willing contributors to and consumers of this kind of qualitative summary of recent conditions on the reservation.

This article was edited and adapted specifically for the AMS Weather Band from the article "Rain Gauges to Range Conditions: Collaborative Development of a Drought Information System to Support Local Decision-Making" by Daniel B. Ferguson, Anna Masayesva, Alison M. Meadow, and Michael A. Crimmins. Any errors or omissions may be attributed to AMS Staff. Copyright remains with the AMS