Battle of the Ice: Sweden's Meteorological Defeat of Denmark in 1658

- By J . Neumann

- Jan 27, 2021

Photo by Ludovic Charlet

Scandinavian history is one rich with battles, raids, and trade; all of which were impacted by weather conditions of the northern latitudes, especially the formation and break up of ice floes throughout the Northern and Baltic seas. This is a closer examination of one weather event that changed the course of Danish and Swedish history.

A little historical background

In the Peace Treaty of Bromsebro of 1645, Denmark ceded two provinces that it held in Norway and the islands of Gotland and Oesel in the Baltic to Sweden. In addition, Denmark agreed that Swedish ships would no longer be subject to search or payment of dues in the Sound, the Belts, and the Elbe.

The Swedish Crown was naturally interested in weakening the Danish domination of the Sound, and the possession of the islands of Gotland and Oesel meant that the Swedes could control access to the inner Baltic, where most of the lands adjacent to the sea were part of the Swedish realm. Control of the access also meant control of the important trade of the Baltic provinces with the West.

The Danes, and especially the king, Frederick III, were determined to recover their losses. An opportunity appeared to offer itself when Charles X, king of Sweden, went to war with Poland. Although the Swedes had successes in 1656, things became difficult for them in the following year. So beginning in the summer of 1657, the Danes took advantage of this by attacking Swedish holdings and hassling their sea traffic. The Danes soon captured the important trading center of Bremen (northern West Germany), which was then held by Sweden. When Charles learned of the Danish attack, he found it a good pretext to extricate himself from the difficult situation in Poland. He marched his army at remarkable speed across northern Germany (a distance of ~800 km), retook Bremen on the way, and then continued his speedy advance via Holstein and Schleswig. Before Frederick III realized what had happened, Charles had conquered much of Jutland, the peninsula that forms the western part of Denmark.

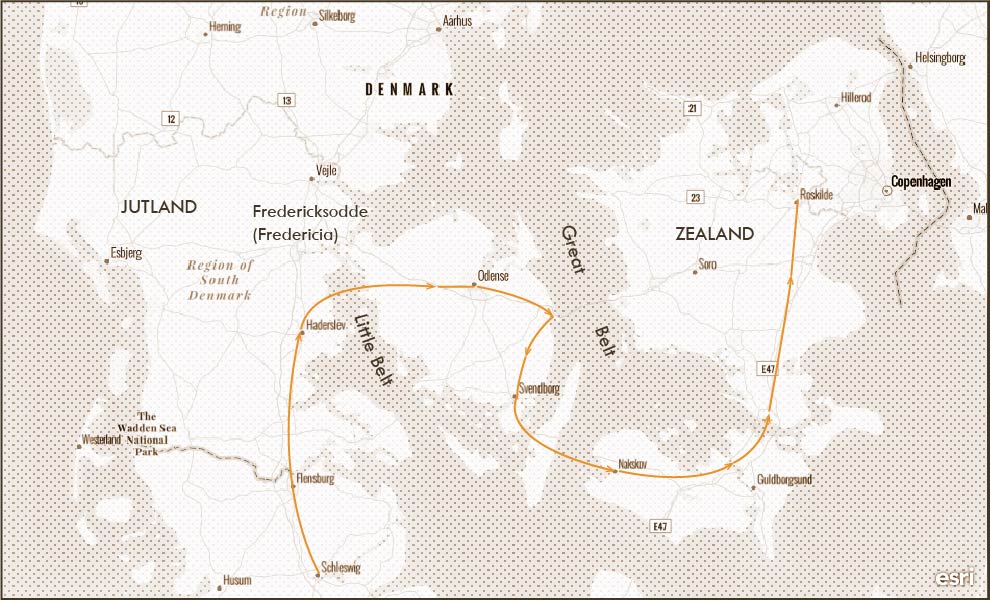

Fig. 1. Map showing the route of the army of Charles X, king of Sweden, across Danish land and sea areas. The crossing from Jutland to Zealand, in February 1658, involved the passage across the frozen Little Belt and Great Belt.

On 3 November 1657, at dawn, the Swedes launched an assault on the remaining Danish stronghold of Fredericksodde (present-day Fredericia) in Jutland, which guards the entrance from the north to the Little Belt (see Fig. 1). This fortress was a recent construction, and it was thought that it would be hard for an enemy to take it. Within hours from the start of the assault, the fortress was in Swedish hands. Its fall caused great alarm in Denmark and anger with the governing circles. At this point the Swedes had little capability for carrying on their conquest to Zealand, the island where Copenhagen is located. Earlier, in September, the Swedes had lost a naval battle with the Danes, and they did not have the naval force to carry the army across the Belts to Zealand. Instead, it was a meteorological development that came to their help.

The winter of 1657-58 in Western Europe

In climatic history, the seventeenth century forms part of what is now generally called the Little Ice Age (LIA). Though not a true "ice age," the earth cooled notably from the mid 16th century to 1850. During this period, the NASA Earth Observatory marks three distinct, maximally cold periods beginning respectively in 1650 and 1770, with the final one in 1850, after which the LIA ended.

Coming to the winter of 1657-58 itself, there are two types of sources from which we can draw some information as to its severity: 1) contemporary and almost contemporary records, diaries, and publications, and 2) a regression analysis of the relationship between air temperature in the Netherlands, measured from 1735, and another "variable" (see Section 2.b) for which data are available since 1657. Of these two source types, only the second is quantitative. However, since the air temperature for the winter of 1657-58 is estimated from a backward extrapolation from a regression equation, the estimate is subject to errors. The written records help to support the quantitative estimates.

Contemporary and almost contemporary records

We learn something of the severity of the winter of 1657-58 from the literature and diaries collected by Francois Arago (1858) and Curt Weikinn (1961). Most of the excerpts from these works given here relate to western Europe, including Denmark.

Arago, the well-known French physicist, was very interested in meteorology and searched the literature available at the time for references to past weather. He quotes 3 excerpts for the severe winter of 1657-58 (Arago, 1858, pp. 279-280); the names of the authors are given by him in parentheses.

1657-1658. This winter was very rigorous in Europe, from the Baltic where Charles X, king of Sweden, could cross over from Fünen to Zealand, over the ice, with his whole army, cavalry, artillery, ammunition waggons, baggage, etc., as far as Italy where the rivers froze so deeply that they could support the heaviest carts. In Rome an immense quantity of snow fell. (Peignot)

In Paris it froze from 24 December 1657 till 20 January 1658 in a manner that the cold was not pungent. On 20 January [however] it [the cold] became excessive because of a strong wind from the NE: few persons could recall having experienced such a penetrating cold. Everything was iced. The bitterness of the cold continued to the 26. On the 27 the air became a little milder and hopes were raised that the freeze would pass; but on the 28, the cold returned and lasted to February 8. On February 9 and 10, the ice and snow which fell in abundance, began to melt. On Monday 11, from two o'clock in the morning, the wind started again from the N and NE so that the waters froze once more. The freezing [icing] was extreme. By sunrise there did not remain the smallest trace of the previous thaw. The rigor of the cold was felt until the 18. . . . (Boulliaud)

In the Provence most of the olive trees perished. (Martius, Patria.)

Weikinn (1961) has published a wide-ranging, invaluable collection of excerpts, continuing and extending the important work begun by Arago. Among his other sources is Volume 8 of Theatrum Europaeum, published in Frankfurt in 1667. Regarding the period beginning about the last week in January, the Theatrum reports that

. . . such an unbearable cold set in that one could cross even the largest rivers as, for instance, the Danube, Rhein, Elbe, Ems, Weser, Main, Oder, Weichsel, Nieper [sic] and others, just as if they were bridges.

Not only did rivers freeze over but also lakes and even sea areas adjacent to western Europe. Writers described sea areas off the coasts of Flanders and the Netherlands (Friesland) freezing, including the Belts and the Sound. One of these excerpts is from the memoirs of Geheimrat Detlev v. Ahlefeld:

. . . . At the beginning of February such a grim cold set in that all streams [sic; meaning the Belts and the Sound] between the islands froze in. . . , against the expectations of all human beings, since nothing like it had they experienced before, the King of Sweden took advantage of this opportunity and marched with his cavalry, infantry and artillery across Langeland, Laaland and Falster and across the streams between them which were now covered by ice, to Zealand.

A reviewer gave another source from the period. An observer in Danzig, Poland, Fredericus Büthner, Professor of Mathematics, listed the winter of 1657-58 as "An intense winter with much snow and frost."

Air temperature in the Netherlands in the winter of 1657-58

Passenger-boat traffic records in the Netherlands along 1) the Harlem-Leiden Canal and 2) the Harlem-Amsterdam Canal allow a closer, quantitative look at the winter of 1657-58. For the first, the records extend from 1657 to 1839 (with the exception of the years 1757-1813) and give the days when the canal was frozen in. For the second, the records begin in 1633 and give the number of trips, which followed a strict schedule unless ice obstructed the traffic. Examining these records in order to reconstruct climatic data, the author de Vries also made use of the air temperature series constructed by Labrijn (1945) for the Utrecht-de Bilt area of the Netherlands, which begins with 1735.

By a regression analysis between the measured air temperatures and the number of days when the Harlem-Leiden Canal was frozen and by a further regression analysis between the traffic data for the two canals, he was able to construct a series of estimated winter temperatures (averages for each of the December-January-February periods) from 1634 on. Naturally, the use of the regression equation for the period prior to 1735 involves the assumption that the pertinent regression relationship before 1735 was the same as from then on.

His result for the winter of 1657-58 was -1°C. Climatological atlases indicate that for the period 1931-60 the average winter air temperature for the region of interest was just over +3°C (Thran and Broekhuizen, 1965). Thus de Vries's figures would suggest that in the Netherlands area (which is somewhat south of Denmark), the winter of 1657-58 was ~4°C colder than the average for more recent years.

A check on the average monthly air temperatures at Utrecht-de Bilt for the period 1735-1944 (Labrijn, 1945, pp. 89-93) indicates that winters colder than -1°C occurred in 1739-40, 1762-63, 1783-84, 1788-89, 1794-95, 1798-99, 1822-23, 1829-30, 1837-38, 1890-91, 1928-29, and 1941-42. Thus, winters colder than that of 1657-58 (on the basis of de Vries's regression estimate) were not at all rare.

The Swedish Army crosses the ice over the Danish sea areas

It seems from the field correspondence between Charles X and Wrangel, the commander of his forces, that the possibility of reaching Zealand from Jutland across the bridge of an ice-covered sea apparently did not occur to them until ~8-10 days before the Little Belt actually froze over. Certainly, their letters indicate that the start of "intelligence" gathering from experienced people concerning the freezing "habits" of the Little Belt did not begin earlier (Grimberg, 1918, p. 585). Meanwhile, the Danes thought that the ice would pin the Swedes down in Jutland rather than offering them a bridge for attack.

A look at Fig. 1 raises the question of why Charles chose to cross at a section of the Little Belt that is relatively wide and not farther north, say near Fredericksodde, where the Belt is quite narrow. The intelligence collected indicated that the narrow part freezes less often, or less completely, because of the swift current in the narrow strait. On 3 February the sea was still open, and, in fact, on the 4th there was a minor thaw. However, on the 5th the freezing began in earnest, even in the more northern sections. On the 6th, the king wrote to Wrangel (Grimberg, 1918, p. 586):

Last night it was freezing again. It is believed that in a few days the ice will carry. A sharp easterly wind helps.

On the night of 8-9 February, Wrangel informed the king that the ice stretched all the way to Fünen, the island that lies between Jutland and Zealand. The crossing of the ice by the Swedish Army, numbering a total of about 10,000 men (Birch, 1938, p. 229), including infantry, cavalry, artillery, equipment, and baggage, began at a point "opposite" the small island of Brandso (see Fig. 1), which offered a resting place. The passage to Fünen, where the Danish forces were lined up, was not without mishaps: two cavalry squadrons and the king's sled (the king was not on it) disappeared under the ice (Birch, 1938, p. 229). Many of the troops were frightened by these accidents, and it was the king's personal example that moved them to carry on.

The Danes attempted to stop the Swedes from passing over to Fünen. A battle developed over the ice (the battle over the Little Belt), but the Danes lost it. The Danish commander and his whole army surrendered. In the meantime, the cold intensified. A graphic description of the cold is preserved in a report of de Terlon, the French envoy to the Swedish Court, who accompanied Charles X on his campaign. He wrote to his king, Louis XVI, as follows (Grimberg, 1918, p. 588):

I assure Your Majesty that it was so cold that one had to use an axe in order to cut up the bread as well as break up beer and wine barrels. The pieces were then allowed to thaw whereupon they hardly had any taste left. Meat was put into heated pans but it was mostly inedible. The King of Sweden merely laughed at all such discomforts although he shared them. His only thought was to succeed in his daring plan.

The far riskier passage over the ice of the Great Belt was still ahead. In this a Quartermaster, Erik Jönnson played a prominent role. The king ordered Dahlbergh to investigate the ice conditions over the Great Belt in between the islands in the south (see Fig. 1). On 14 February, Dahlbergh and 40 cavalry rode at full trot from the SE corner of Fünen, via the islands of Taasinge and Langeland, as far as the island of Laaland and measured the thickness of ice, including places where the current was strong. In the evening, the king discussed the matter of crossing with his senior officers. Wrangel and others categorically opposed taking the risk (Grimberg, 1918, p. 587). At night the king could not sleep and called for Dahlbergh. When Dahlbergh took the risk on his conscience, the king decided that the chance must not be missed, and later that night, the crossing began. The notes of the French envoy, de Terlon, preserve something of the fearsome aspects of the march across the sea ice (Krabbe, 1950, p. 144):

It was terrifying to march at night across the frozen sea, since the multitudes of horses that made their way caused the melting of the snow ["neige"] in such a manner that two feet of water [sic; slush?] was over the ice and one feared all the time to find the open sea somewhere. Many sledges were lost over weak ice.

On 16 February the Swedish forces were on the island of Langeland. It was from here to the island of Laaland that the Great Belt was to be crossed. This was a distance of over 18 km as compared with the 12 km from Jutland to Fünen. After passing the island of Falster on the 19th, Charles X and his advance forces reached Zealand on the 21st. Surprised and defeated, the Danes asked for peace, and a treaty was concluded at Roskilde, ~30 km west of Copenhagen, on 1-18 March 1658.

Following the Roskilde Peace Treaty, Denmark lost all her territories in what is today southernmost Sweden, some areas held in Norway, and the island of Bornholm, close to the entrance to the Baltic; in addition, the Danes had to pay heavy indemnities. One of the significant and lasting aspects of the Roskilde Treaty was that Sweden reached for the first time her present territorial extent on the east side of the Scandinavian peninsula.

The passage of the frozen Belts was a great gamble. Had a sudden thaw set in, the Swedish forces could have found themselves trapped on the Danish islands (if not in the sea). One example for a large temperature rise in a matter of 2 days can be seen from the winter of 1967-68. The (then) West German Weather Service (Deutscher Wetterdienst, 1968) published daily temperature anomalies for northern and southern Germany. On 13 January 1968, the mean temperature for northern West Germany was 10.7°C below the appropriate average; on the 15th the mean rose to 6.5°C above the average, a rise of 17°C in 2 days.

Actually, the ice helped the Swedes in one other way: it prevented other powers, such as the Netherlands, from coming to the aid of Denmark. Certainly in the winter of 1657-58 the Latin proverb "'Fortes Fortuna Adjuvat" (Fortune helps the brave) proved true, for once at least.

Role of ice in earlier Scandinavian history

One may expect that in such cold climates as those of the Scandinavian countries, ice may have played an important role in other periods of history. Indeed, in 1581 in the war between Sweden and Russia, the French born Swedish commander Pontus de la Gardie (about 1530-1585) of Erik XIV, king of Sweden, crossed the sea ice over the Gulf of Finland from Vyborg to the opposite coast of the Gulf. In all probability, this passage involved a distance of close to 100 km as compared with the distance of just under 20 km involved in the crossing of the Great Belt. Other historians also mention that when the Danes invaded Sweden in 1520 and again in 1567-68, the cold had made a way over lakes and marshes that would have been impassable otherwise.

Some long-term consequences of the winter of 1657-58

The great cold of the winter of 1657-58 also had some long-term consequences. We have quoted Arago in Section 2 who recorded that large quantities of snow fell in Rome and in Paris. Handwritten Swiss chronicles, held in the Wintertur Municipal Library (Wolf, 1864, p. 181), say that much snow fell. Grimberg (1918, p. 590) mentions that when the forces of Charles X reached Zealand and advanced toward Copenhagen they went through snow drifts as high as houses. The infantry had a hard time to get through. When at long last spring came and the snow melted (it was a cold spring and summer too), the floods hurt the growth of crops, leading to a steep rise in grain prices.