Perils of Free Ballooning Make Great Adventure

- By Lieutenant William O. Eareckson

- Jan 5, 2021

Quoted from Boston Transcript, July 14, 1928

Lieutenant William O. Eareckson, aide to Captain William E. Kepner, and pilot of the United States Army Entry No. 1 in the 1928 National Elimination Balloon Race, tells the following interesting story of their experiences on this flight:

On May 30, at exactly 5 P. M., Eastern Standard Time, a great throbbing sigh, followed by a ringing cheer, went up from the multitudinous assemblage gathered at Bettis Field, Pa., for it was then that, in the words of the program, the first racing balloon "leaped into space."

The weather all day had been cloudy with occasional showers, accompanied by some mild thunder and lightning, and it was with a feeling of relief that we saw Old Sol break through the cumulus canopy and smile down from his azure setting about a half hour prior to the starting of the race.

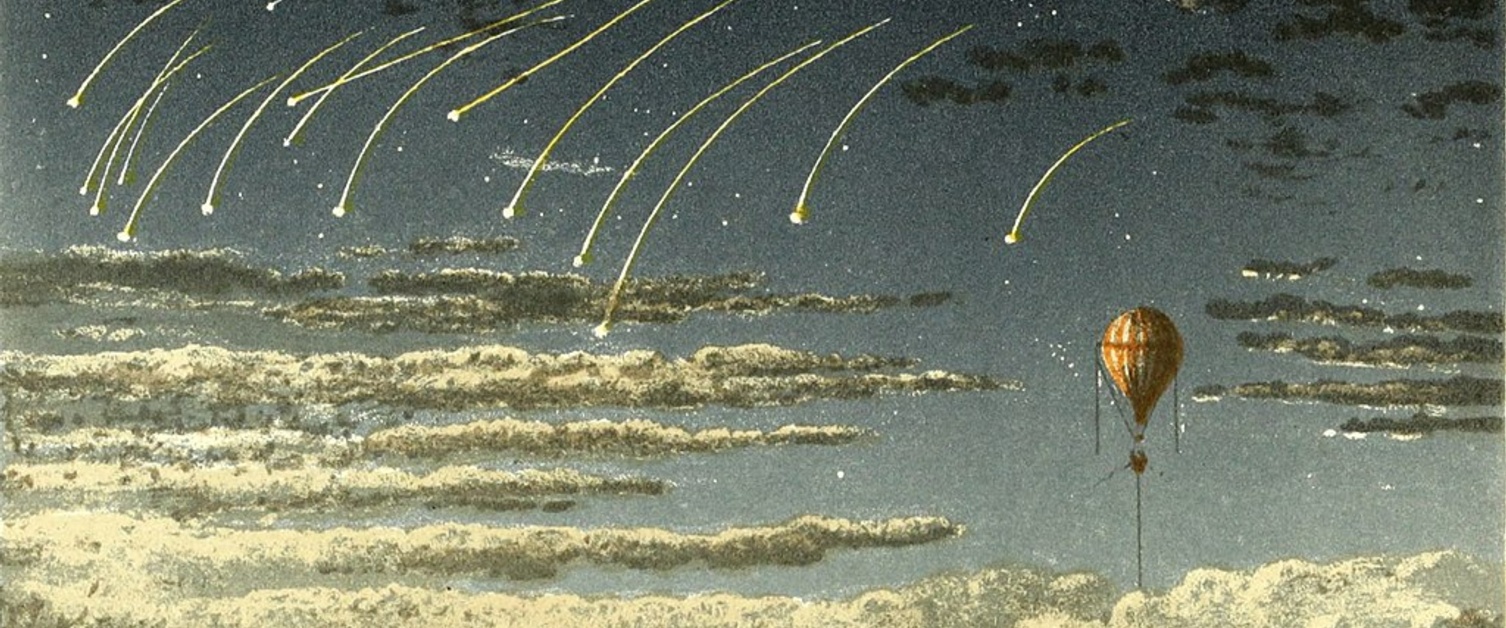

Beginning at 5 P. M., the balloons took off at five-minute intervals until all fourteen entrants were in the air and heading in a general easterly direction, the lower ones going a bit north of east, the higher ones a bit south of east. Our balloon, the Army Entry No. 1, being in ninth position, took off at 5.45 P. M., and flying low headed up towards New England. We had hardly left the ground when we saw that directly ahead of us and about ten miles distant was a high piled cumulus cloud from which issued ominous rumblings, flashes of lightning and, as we found out later, rain, hail, death and destruction. Having been in storms before, we were not dismayed and even decided to stay low in order to save gas, run into the storm to gain speed and stay with it until night caused it to dissipate.

We had not long to wait. In about forty minutes our speed had picked up from eight miles an hour to twenty. We were directly under the cloud and starting to rise with the rising convection current that fed the cloud. Wishing to stay low, we valved, but continued to rise even more rapidly as the current became stronger. We reached our pressure height at 1000 feet and continued rising at a rate of from 800 to 2000 feet per minute, spilling gas from the appendix as we went until at about 5000 feet we began to descend as rapidly as we had climbed. And with us came the rain in gobs and scads, rivulets and small oceans, while we whirled, eddied, jostled and spun in the most violent set of cross currents I have ever encountered, meanwhile being shocked when the lightning sizzled and jolted when the thunder roared.

More or less expecting to be struck by lightning, we put on our parachutes when we entered the clouds, and, figuring that if we were, we might be only knocked out rather than killed, we took this precaution. Sitting on the edge of the basket with our centers of gravity well out in space, we tied strings from our rip ring to the basket suspension ropes so that in case we were knocked out we would fall out of the balloon, our parachutes would open and we would descend in one piece, rather than with the unmanned and probably burning balloon.

Thus we rose and descended until we left the cloud and saw the earth 1500 feet below. Then we got busy checking the descent of our craft. Alternately we poured sand, bag after bag, until we had poured twelve hags and checked our downward velocity to 800 feet per minute. Then we cut loose our drag rope so that it hung down below us, and waited for the earth to fly up and spank us.

While waiting I had a chance to look around and saw balloons all about us, some of them performing the most undignified stunts and all of them showing the loss of from a third to one-half of their gas. Northeast of us the Pittsburgher chased the Army Entry No. 2, piloted by Lieutenants Everts and Ent, up a valley; north of us Captain Honeywell sat like a huge stationary mushroom in a small terrestrial depression; while from above Van Orman and Morton started down, caught up with us and flashed past us in a shower of sand as they cut bag after bag in a vain attempt to check their descent. We watched them strike, and up they came again like a rocket, disappearing in the cloud above.

Then we hit. And how! And hardly had we hit than the ground wind had us in its clutches, racing us over the ground, sometimes at velocities of from fifty to sixty miles per hour while our static heaviness caused us to kiss Ma Earth every three or four hundred yards. There is nothing on earth more exhilarating than hedge-hopping in a free balloon at a high rate of speed. We crashed through trees, fences, telegraph lines, always keeping the balloon statically heavy so that we would lag behind the central fury of the storm by our friction over the earth until, as we sped over a small rise, we found ourselves face to face with the worst menace to free ballooning—a high tension power line.

With about 30,000 cubic feet of very inflammable hydrogen gas only a bare ten feet above our heads, with every stitch of our clothing and equipment soaking wet and oozing water, standing knee deep in sand, instruments, water, angel cake, ham sandwiches and bananas (all this chaos due to our violent contact with terrestrial obstacles) we sped at the rate of fifty miles per hour toward six power lines, each carrying about 50,000 volts of most excellent electricity and so placed that they would strike us just about three feet above the load ring. We knew that the instant any two wires were short circuited there would be spark enough to fire a year-old Dunhill lighter, and that even the smallest spark would ignite the gas, thereby causing all young officers below us to gain two files on the promotion list.

What people do at times like that is interesting. Vogue would have had us light a Murad. But we were too wet for that and, besides, we hadn't any Murads. Possibly we should have read a chapter of the scripture, picked a lily and reclined in a pose suitable for marble slab decoration purposes. What we actually did was call a certain famous biblical character most familiarly by his two first names, grab a handful of wet hemp, and set ourselves for the shock, be it dynamic, electrical or thermal.

It was none of the three. Just then Lady Luck tossed a horseshoe at the seats of each of our soggy trousers and we went through the power lines like Charlie Paddock through a yarn thread. Allah alone knows why, but there was no spark as we broke all six wires and kept moving toward where a railroad ran in the shade of a twelve-wire telegraph line. Comparatively, that telegraph line was as harmless as a garter snake beside a rattler. It was less venomous, but it was stronger. We hit it, crashed through eight wires, slid along the remaining four until we hit a pole, lifted the pole out of the ground, went on a few yards with the pole wedged firmly between two suspension cables and came to a halt in a grove of trees on the edge of a stream. "And there we were ketched," and thrashing around like a tomcat in a croaker sack.

But our apparent misfortune was our salvation. The storm we were riding, though violent, was small, typically Napoleonic, and the five minutes we used in extricating ourselves from the spreading arms of the pole's cross piece was sufficient to allow the storm to pass on. By the time we were free, the storm had left us and was already abating.

Free of the pole, our next problem was the trees, and this solved, we yet had to make ourselves statically light enough to float in the air. This was accomplished in a rather unique manner. Around our basket we had placed, prior to the take-off, a rubberized fabric envelope, so that in case we landed in water—the Great Lakes, Chesapeake Bay or what have you —our basket would become a boat in which we could float for a time and remain dry. The rain reversed the process by placing the water inside the basket cover so that there we stood, ankle deep, in about four hundred pounds of water. This water had replaced the sand we expended during the storm and gave us a superfluity of ballast besides. We knew that if we lost all the water, literally "the sky would be the limit" of our altitude. But we must lose some, the superfluity, or stay put. What we did was this: Very carefully with a large sheath knife we cut a small slit in the envelope, well over in one corner of the basket. Then we stood over that hole, our weight tilting the basket that way until enough water had drained out to make us sufficiently light to take off. As we started to rise, we walked to the opposite corner, tilting the basket in the other direction, and our theory worked. The hole was above the remaining water, which accompanied us as ballast.

Now that we were satisfied that we could fly, our attention turned to ourselves, whom we found as pathetic spectacles as Chester Conklin in the "Fire Chief." Soaked to the skin, our food a total loss, we faced the already lowering night, which bid fair to be rather chilly, without too much enthusiasm. The balloon, shedding water a bit faster than the contracting gas, due to increasing cold, lost lift, needed no attention, but continued to gradually rise and slowly drift in a southeasterly direction. This gave us a chance to take off and wring our clothing which, being the driest we had, we put back on.

By this time we were at 5000 feet and our speed to the southeast had increased to fifteen miles per hour. But, Oh, Boy! it was cold. Our hands were shrivelled from being wet, our lips were blue, and our teeth chattered like two skeletons with inflammatory rheumatism having congested chills on a tin roof. At 5200 feet it started to snow, and at 7400 feet, our maximum altitude, ice began to form on the rigging, in our drinking water and on our clothing. But our speed steadily increased until it reached about thirty miles per hour, and our spirits accordingly rose.

All through the night, which was alternately moonlit and overcast, depending whether we were above or below the clouds, we froze and thawed. Freezing as we rose, thawing as we reached the warm strata of air which extended to about 500 feet above the treetops. As the night passed we entertained each other by recalling experiences during which we had been the hottest.

The flight continued like Briggs' dialogue of Mr. and Mrs., "far, far into the night." The application of our knowledge of navigation rather lost itself by the wetness of our maps and our more or less natural mental apathy and physical inertia. Besides, when we moved our bodies found previously untouched areas in our clothing that, due to lack of contact, were surprisingly cold. Our navigation, then, consisted in an occasional compass check of our direction and conjecture, from our general knowledge of the country, of what town that patch of lights might be or what river that silver ribbon was.

And so on unendingly till morning when, just as the dawn broke, we drifted out over the Rappahannock River and became sufficiently alarmed to find the least sodden map and accurately check our location.

Our flight ended due to the proximity of the Atlantic Ocean and the very commendable hesitancy on our part to dim Lindbergh's glamour by making a transatlantic flight in a free balloon. For these reasons, then, we landed at Weems, Via., rolled and packed our balloon, and the flight of the Army Entry No. 1 was over. Having located and voraciously attacked large quantities of heat-cured groceries, we hied us to a most generously proffered bed and hauled down the mental curtain for a long intermission.

It was not until we awoke some hours later that we learned about the storm-caused disaster, or that we had won the race. And as one counteracted the other, our elation at winning was overshadowed by our sorrow of having lost the friendship of two real he men, two regular buddies —Evert and Morton.

Col. William O. Eareckson enlisted in the Army at the age of 17, two months before the US entered World War I. He was wounded in France, then reenlisted in the hope of entering West Point, which he did through a presidential appointment in 1920. He became one of the Army’s top balloon pilots, and in 1928 won the Gordon Bennett International Balloon Race. He went on to a distinguished career as an airplane pilot, using his ballooning experience and weather knowledge to create innovative bombing tactics against the Japanese in Alaska during World War II. Read more of his biography here.