Can A Hedgehog Forecast Rain?

- By AMS Staff

- Nov 20, 2020

While the scientific methods have varied a great deal, weather forecasting has been a subject of human endeavor for as long as we have written records! Ancient forecasters used everything from cloud observations to jellyfish sightings to predict the weather and help them make their most important decisions on topics from going to war to sowing crops.

The First Weather Records

The earliest known written weather records that survive are those inscribed on the so-called "oracle bones" of the Shang Dynasty (circa 18th to 12th century, B.C.). These are weather records engraved by knife on ox bones or turtle shells by Shang diviners. These diviners occasionally made weather forecasts for the Shang kings based on patterns of cracks that formed in the bones or shells when placed in a fire. They would then note down the actual weather that had occurred on that same piece of bone or shell for verification purposes. These supply incredible eyewitness records of the weather from ancient China.

Government Forecasters of the 7th Century

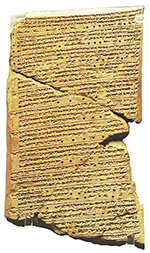

In the cuneiform library of Ashurbanipal, from the ancient city of Nineveh, there are several tablets showing that weather forecasting was practiced on an extensive scale—and as a government enterprise!—as early as the seventh century B.C.E. As public officials, Assyrian astrologers were responsible for predicting a variety of events, including droughts and floods. Their forecasts were based on omens of many kinds. This included atmospheric phenomena, such as the luminous circles around the sun and moon known to modern science as halos and coronas. Atmospheric information was just one part of their weather toolkit though. A drought or a flood was as likely to be foretold from the liver of a sacrificial animal as it was from the appearance of the sky.

In the cuneiform library of Ashurbanipal, from the ancient city of Nineveh, there are several tablets showing that weather forecasting was practiced on an extensive scale—and as a government enterprise!—as early as the seventh century B.C.E. As public officials, Assyrian astrologers were responsible for predicting a variety of events, including droughts and floods. Their forecasts were based on omens of many kinds. This included atmospheric phenomena, such as the luminous circles around the sun and moon known to modern science as halos and coronas. Atmospheric information was just one part of their weather toolkit though. A drought or a flood was as likely to be foretold from the liver of a sacrificial animal as it was from the appearance of the sky.

Here are some of the formal rules for Assyrian forecasting: "If lightning flashes from south to east there will be rain and floods." "If there is lightning in the west the weather god will inundate the land of Amurru (Palestine)" "If the voice of the weather god (thunder) is heard in the month of Tammuz the crops will prosper." "If the sun is surrounded by a ring there will be rain and a change of weather." "If it rains eight days in the month of Nisan, this means riches for the people."

The Origins of "Meteorology"

Farther to the west, Aristotle wrote his treatise known as the Meteorologica in Greece around 350 B.C. Providing an examination of all features of the things of the air, or “meteora,” it includes studies of rain, clouds, winds, thunder, earthquakes, etc. Much of the book provides explanations for weather phenomena by explaining how the forces of earth, air, fire, and water interact. How do you think his explanation of the atmosphere compares to modern science?

“For the air round the earth is necessarily all of it in motion, except that which is cut off inside the circumference which makes the earth a complete sphere. In the case of winds it is actually observable that they originate in marshy districts of the earth; and they do not seem to blow above the level of the highest mountains. It is the revolution of the heaven which carries the air with it and causes its circular motion, fire being continuous with the upper element and air with fire. Thus its motion is a second reason why that air is not condensed into water.

But whenever a particle of air grows heavy, the warmth in it is squeezed out into the upper region and it sinks, and other particles in turn are carried up together with the fiery exhalation. Thus the one region is always full of air and the other of fire, and each of them is perpetually in a state of change.”

The Meteorologica became an authoritative work on weather theory in much of Europe. There were a few successors, however, who expanded on Aristotle’s ideas and produced theories about topics he had not covered. Perhaps the most notable of these was Theophrastus of Eresos (ca. 372 to 288 B.C.E.). While the Meteorologica was a work largely concerned with theory, Theophrastus’ two short books focused on creating forecasts from direct observations of the winds and weather signs. His emphasis on practicality and the importance of regional observation for good weather knowledge is clear: “…good heed must be taken to the local conditions of the region in which one is located. It is indeed always possible to find an observer (of the weather), and the signs learnt from such persons are the most trustworthy.” (Translation from the Loeb Classical Library)

In addition to practical advice on weather observation, Theophrastus also laid forth some key rules for weather forecasting. Have you ever heard the phrase “Red sky in the morning, sailors take warning”? This is used to mean that stormy weather is coming. That phrase is taken from the New Testament, but the idea was written down over three hundred years earlier by Theophrastus, who noted that a red sky at dawn was a sure sign of rain.

Other signs of weather have perhaps not stood the test of time as well, but if you’ve got a hedgehog living nearby, you can test this one for yourself: “If the feet swell, there will be a change to a south wind. This also sometimes indicates a hurricane. So too does it, if a man has a shooting pain in the right foot. The behavior of the hedgehog is also significant: this animal makes two holes wherever he lives, one towards the north, the other towards the south: now whichever hole he blocks up, it indicates wind from that quarter, and, if he closes both, it indicates violent wind.” (Translation from the Loeb Classical Library)

Precision Science in Iran

Meanwhile, in other areas of the world such as India, the Middle East and Near Asia, Southern Spain and North Africa an immense amount of meteorological study and knowledge was being applied to everything from poetry to agriculture. In the 9th century, the naturalist Abu Hanifa Dinawari drew on even older sources to write a highly detailed treatise on applying meteorology to agriculture. In part one of this six volume work he covered the sky, planets, constellations, the lunar phases, and atmospheric phenomena and water sources. An English translation is available here

In addition to this agricultural revolution, many other parts of the natural world were under investigation. In 1021 C.E., Ibn al-Haytham wrote about the atmospheric refraction of light causing the morning and evening twilight, including noting that the sun must be at 19 degrees below the horizon before twilight can begin. His mathematical proofs also included a geometric demonstration to measure the height of the Earth’s atmosphere at 49 miles, which is only one mile off from our modern measurement of 50!

Of course this is only a small subset of historical scientific and weather investigations. Scientists all over the globe recorded atmospheric phenomena in a variety of ways, and created technology to more accurately measure the world around them. And ancient and medieval scientists contributed an immense amount to weather knowledge by recording their observations and laying the foundation for future scientists. You can help contribute to future weather knowledge by contributing your own observations to volunteer networks such as CoCoRaHS and the Cooperative Observer Network or even in decoding old weather records through citizen science projects. And, of course, share your observations with the rest of the Weather Band community by joining the community discussions!