The 1938 Hurricane

- By Dr. Lourdes Avilés

- Jul 27, 2023

From the Keene, NH Public Library

The One to Which All New England Hurricanes Are Compared…

I have said that phrase so many times by now that I am not sure if I read it somewhere or I came up with it myself. The Great New England Hurricane of 1938 undoubtedly IS the one to which all other New England hurricanes are sooner or later compared. There have only been three others of comparable combined strength and widespread devastation since the colonization of the region: The Great Colonial Hurricane of 1635, The Great Gale of 1815, and the subject of our musings today. Geological studies expanding the timeline back 1000 years suggest three more, for a total of approximately six such storms per thousand years, an average of one every century or two.

Growing up in Puerto Rico, hurricanes, or more specifically, the threat of hurricanes, was a forming part of my upbringing. Any time when there was the possibility of one coming our way, I was glued to the TV or the battery radio, sometimes plotting the coordinates on a map that had been published in the newspaper at the beginning of the hurricane season. My childhood home was too close to the ocean for comfort, and we would instead go to my grandparents’ house which, though also close to the ocean, was on higher ground. There was this sense of wonder and mystery to the experience that is hard to explain with words. The whole extended family, cousins and all would join there together, kind of a party for the little ones, but the atmosphere felt heavy and ominous. I was fascinated by my grandfather’s stories about experiencing Huracán San Felipe, a category 5 hurricane that came through the island in 1928 (which happens to be the first category 5 landfall on U.S. territory, and the same storm that continued on and killed thousands off Lake Okeechobee in Florida, but all of these are stories for another day). I never gave much thought to New England hurricanes until I moved to New Hampshire to join the meteorology faculty at Plymouth State University. It was then inevitable that I would be captivated by this exceptional storm, so rich in science and history, and human experience. My explorations grew into enough material to speak for ten hours and write ten of these blog posts (maybe more), or for that matter, write a book, which I eventually did.

It was Wednesday, 21 September, 1938. After a particularly wet summer, and several consecutive days of rain, it had finally stopped overnight. Some parts of the region were even seeing some sunlight that morning. People went about their business: work, school, groceries, some downtown shopping, or even a beach picnic to take advantage of the break in the rain. The Weather Bureau’s forecast in the morning’s newspaper spoke of rain, possibly heavy, coming later that day, followed by colder conditions late that night or Thursday, so the break would be short lived. The forecast was basically describing the expected passage of a cold front, but even though the theory of what was commonly dubbed “air mass analysis” had been developed in Europe a couple of decades before during and after World War I, the terminology and forecast usage (and the symbols as well) were not yet settled. In fact, it was not until 1941 that the Weather Bureau first included a front in their daily weather maps. This is, however, also a story for another day.

Everything was calm: the weather, the town. Most of the summer dwellers had gone back home. Continuing news of political instability in Europe (where World War II would ensue exactly a year later), and a hurricane that had just threatened Florida, were also in the papers that morning. Little did those reading the news know, that before the day was over, hundreds would be dead, and everything around them would be devastated and filled with chaos. The Great Hurricane, which had still been a few hundred miles to the south early in the day, slammed without warming onto Long Island and southern New England that afternoon, and continued inland into northern New England as it expanded its blanket of destruction that evening over an area that was too large for a tropical hurricane to do on its own, before finally spinning itself down and dissipating over Quebec the next day. The storm, which made landfall as a major category 3 hurricane (even though I should note that the hurricane rating categories wouldn’t be developed until more than three decades later), was transitioning into an extratropical storm, and the timing was the worst-case scenario. The coast suffered major hurricane effects and damages, including a severe storm surge and urban flooding, with some areas experiencing a maximum of 120 mph sustained winds, all together causing massive structural damage. The storm weakened as it transitioned into an extratropical storm, but it also expanded and a much larger area experienced intense rain and winds that were still strong enough to cause a major tree blowdown.

That last statement, is quite an understatement. The massive tree damage through the entire region (including Long Island, southern and Northern New England, plus other portions of the northeast) was unimaginable. It amounted to hundreds of millions of trees over an area of about 15 million acres. The storm left behind a tangle of trees, electricity and telephone cables, landslides, and washed-out bridges, railroads, and broken dams. This region that was less than a month from experiencing the majesty of its famous fall foliage, was instead prematurely thrown into a winter-like scene, but it was worse than that. Winter’s lack of foliage is expected, and can be quite beautiful. This was devastation, everywhere; and the beloved mountains, lakes, river views, hiking trails and picturesque towns were all heavily damaged. The heartbreak that accompanied that loss was quite palpable to me so many decades later. I specifically remember reading a line that said something like “our forest friends are slain…” and many of the poems, songs, drawings, and other pieces that I have come across, have to do in one way or another with the loss of the trees.

The extratropical transition of the Great New England Hurricane calls for more discussion. Tropical cyclones are, generally speaking, smaller, symmetrical, warm cored, powered by ocean heat transfers, and live in warm-humid environments without fronts, while extratropical cyclones are much larger, asymmetrical, cold cored, and get their energy from favorable interactions with the upper level patterns in the midlatitude atmosphere that result from the frontal contrast in moisture and temperature environments. It is not at all rare for a hurricane to transition into an extratropical storm after it recurves and starts interacting with the midlatitude flow. In fact, in order to maintain enough strength to survive, the storm must latch onto a new source of energy than its original oceanic source. The details matter, but in general, if a transitioning storm can line up with the correct location of the eastern side of a trough in the flow of the jetstream, it can temporarily syphon enough energy to survive the cold waters of the north Atlantic or the inhospitable land after landfall. This midlatitude flow also steers the storms, determining their specific northward/northeastward track. About 50 percent of Atlantic hurricanes do this to different degrees.

Something that does not happen as often, is for the trough in the Jetstream to be as deep and strong as it interacts with a hurricane as in this situation. Hurricanes normally accelerate from their usual ten or so miles an hour over the tropics, to twenty or thirty miles an hour as they recurve northward, but such an intense flow caused this storm be move way faster than that, at least fifty miles an hour, maybe even faster. This is why it is sometimes also referred to as the Long Island Express. This exceedingly fast northward motion appears to be a common characteristic between the three Big New England Ones mentioned above.

Searching for publications about the storm, I came across Pierce (1939), a relatively well-known post mortem report, summary, and study of the meteorological conditions associated with the storm, published exactly a year later. I had looked at every single hurricane-related study in the Monthly Weather Review for the nearly seven decades since its first publication. I found many hurricane reports, but this paper was different. It seemed much more in line with a modern synoptic analysis and case study of a meteorological phenomenon than any of its predecessors, definitely ahead of its time. It was written by Charles H. Pierce, the junior forecaster that was the only one to realize, against the forecast his superiors had made, that the storm was coming straight for New England rather than recurving into the North Atlantic. This fact, however, is not mentioned in the article. This is hardly an unknown fact, but it took me some time to realize that the author of the amazing paper and the forecaster of the fabled story were one and the same. I clearly remember the excitement of discovery when I made the connection. I have tried to learn as much as I can about what happened at the Weather Bureau headquarters office that day from as many direct and indirect sources as I could find and, as much as the details are yet another story for another day, I was able to confirm that Pierce did make such a forecast, but there was likely no confrontation with his superiors at any time. I also feel certain that Pierce would not have been able to anticipate how quickly it would happen and how bad it would be.

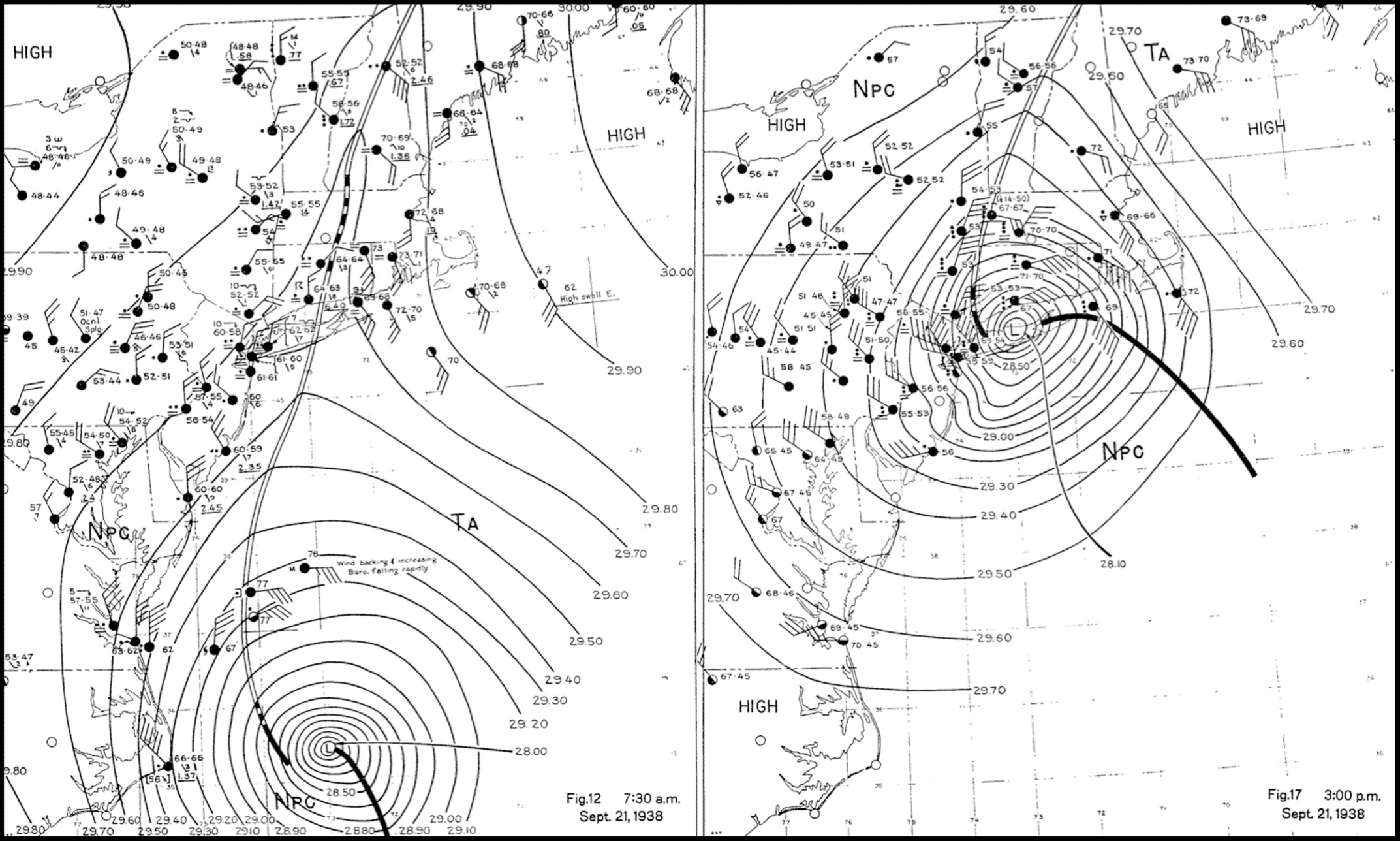

Pierce (1939) contains more than sixty figures, mostly surface and upper air maps with observations and analysis. The map on the left represents the position of the storm at 7:30am, with the center near Cape Hatteras. The one on the right shows the storm at 3:00pm, right after its Long Island landfall, as it was starting to make its way deep into New England. I used these figures in Avilés (2013) to both to illustrate the speed of motion of the storm, and to show the detailed analysis Pierce put together, as well as his depiction of cold and warm frontal boundaries, very different than how we would depict them today.

Something that caught my attention in Pierce’s study was the description of the extratropical transition of the storm in the way that one might talk about a phenomenon for the first time, feeling that he needed to say that it might sound “like an absurd statement.” He explained in detail how this likely worked and did not use standard language. “Oh my, did Charlie Pierce discover extratropical transition,” I asked myself, once again gripped by a sense of wonder about this story. This gut feeling was not enough, however. I needed to carefully look at what might have been known about it before 1938. I searched and read and was ready to declare him as the “discoverer” when I found a note on typhoons by Visher (1922) that described his personal communication with typhoon experts who expressed their opinion that “when sufficient pressure data [became] available… a close study [would] prove that most typhoons give rise to what are generally known as extratropical cyclones” (recall that typhoons and hurricanes are regional names for the same phenomenon of tropical cyclones). I had to adjust my declaration to Pierce being the first to observe the extratropical transition of a tropical cyclone based on the analysis of available data, still a noteworthy accomplishment. I do believe, however, that he came to his conclusion independently and there is no indication that he had knowledge of the previous speculations about typhoons. To my knowledge, until my publication sleuthing came to fruition, Pierce had not been given any credit for first observing the phenomenon anywhere in the extratropical transition or otherwise literature, so I was happy to finally give him this much deserved recognition. A few years ago, Pierce’s son and his family sought me out and visited me to chat about their father/grandfather and it was my absolute pleasure to talk to them about what I had found out as well as to listen to their stories about who he was as a person.

So it was, that this fast-moving extratropically-transitioning hurricane came and went through in the matter of just a few hours. Nobody alive in the region had ever seen such devastation from a storm of tropical origin. In fact, the last time that any kind of major hurricane landfall occurred in New England was the year before the agency that would later become the Weather Bureau was established in 1870; and that storm only caused localized damage during its landfall. You could have worked as a forecaster for seventy years and never have seen a major hurricane landfall in the region. It was understandable, then, that New Englanders would not be expecting such a storm, and many did not know what had hit them, certainly not at first. What followed were days, weeks, even months and years, of recovery.

I have only been able to scrape the surface here. The meteorology of the storm, its hydrological, geological, ecological effects, its economical, societal effects, its direct and indirect influence in modernizing the practices of the Weather Bureau, as well as the fascinating political and social circumstances of the time, and how it all weaved together, are also worthy of discussion. Additionally-relevant are the history of the science and forecasting of hurricanes, as well as the basic and deeper science of these storms and their effects. There are also the remnants of the storm to talk about: visible scars deep in the forest, sentinel pine bridges, furniture, and souvenir disks, poems, songs, countless diaries, scrapbooks, drawings, stories, letters, newspaper special issues, picture collections, technical reports. The 1938 Hurricane still comes up in emergency management preparedness assessments and plans, as I was surprised to learn while attending one of these a few years ago. As I said before, I could continue talking about everything related this storm for hours. There is an accessible richness in breadth and depth that not too many other storms have.

The city of Hartford, CT produced these souvenir disks by attaching a brass disk to wooden disks cut from fallen trees. The center shows the city’s shield, which serendipitously, also proudly states its motto, Post Nubila Phoebus, which can be translated to “After the Clouds, comes the Sun.” I tell the story in detail about the information I found about them, in the book’s website where I also tell stories about other artifacts and additional resources I have come across since the publication of the first edition of the book, and my visit with the Pierces.

When I first decided to look into this storm more purposefully around fifteen years ago, I didn’t know that I was in for a lifetime trip. The more I looked, the more I found, and the more interesting that it all seemed, well beyond the meteorological story. I was fortunate to get my book published by the AMS a few years ago, but my story with The Hurricane did not end then. I have given countless presentations, both general and technical, about a wide range of related topics (the Pierce story, using the storm to teach hurricane science, the hydrological and precipitation data, the art produced as a result of the storm, the role of women, even the effect on birds, as well as general public “science and history” talks at local libraries and historical societies). Sometimes during these presentations, thanks to members of the audience, I become aware of a new source, a new piece of information, a new human-interest story, which leads me to continue my investigations. Clearly, I will never be done learning about and being fascinated by this magnificent, yet admittedly terrifying, storm.

Dr. Lourdes B. Avilés is a professor of meteorology at Plymouth State University and the author of "Taken By Storm, 1938". She has also been involved in research on tropical cyclone formation from African easterly waves, air quality forecasting methods, and the in the development of AMS curricular guidelines for undergraduate atmospheric science and meteorology programs.