You Say "Sleet", I Say "Snow Mixed With Rain"

- By Bob Henson

- Feb 22, 2023

boulder-snow-henson-3.20

During the last few days of February 2023, a sprawling, intense frontal zone was set to produce a wild smorgasbord of winter weather across the United States. Possibilities ranged from hail, cold rain, and even snow at unusually low elevations across California to an exceptionally heavy snowstorm with blizzard conditions from the Dakotas to Minnesota.

Frozen precipitation doesn’t care how we refer to it, of course, but there are still some interesting and helpful distinctions in the terms we use to describe snow and its icy cousins.

When I wrote two books for the British-based travel publisher Rough Guides some years ago, I quickly discovered that people in the United Kingdom talk about weather a bit differently than we do in the United States. Perhaps the biggest surprise was finding out that Brits use the term “sleet” to refer to what people in the U.S. and Canada call “rain mixed with snow” (or vice versa). This usage goes all the way back to the 1300s, when the Old English noun slete and the verb sleten referred to mingling of rain and snow.

English speakers who came to what is now North America may have used “sleet” in the British sense for quite some time. Of course, snow does mix with rain here, but we also get something that’s seldom seen in the British Isles: “ice pellets”, the more formal name for what Americans call sleet.

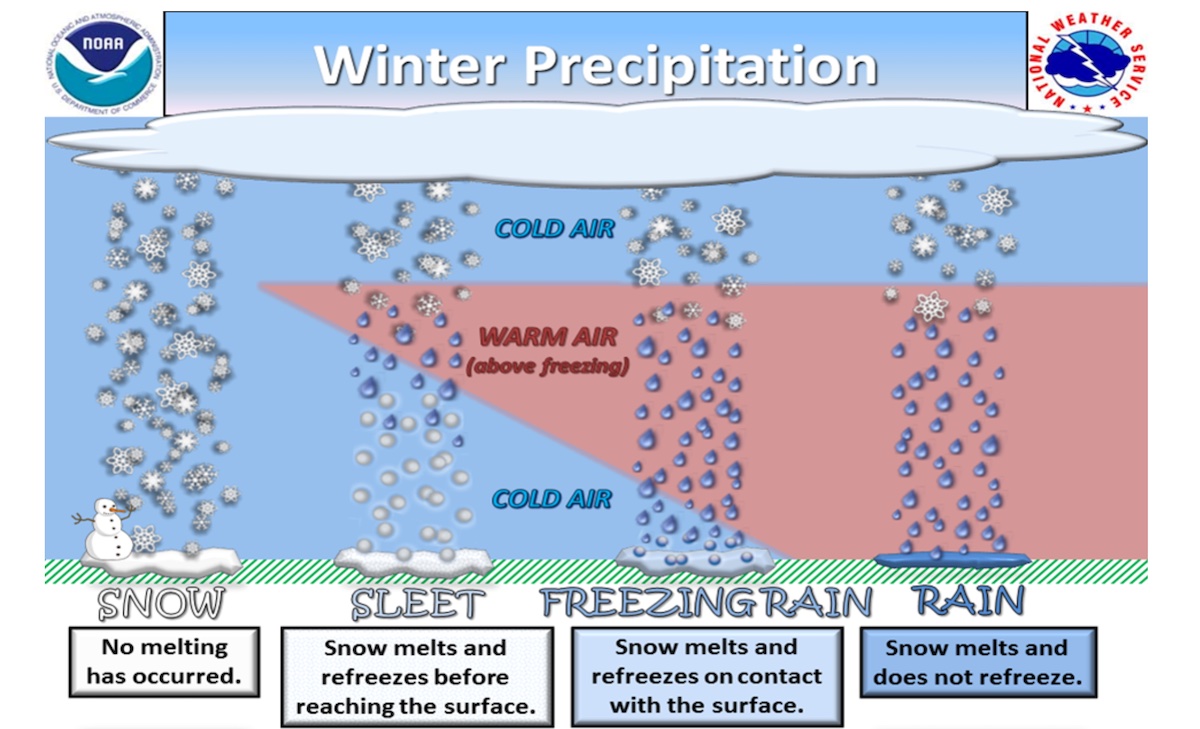

To help us plow into this terminology a bit more deeply, let’s look at the vertical layers of the atmosphere that give us each type of winter precipitation, with some help from the handy graphic below created by the National Weather Service.

(Illustration courtesy NOAA/NWS Northern Indiana Office)

- The various forms of ice crystals known as snow normally develop thousands of feet above the surface at temperatures below freezing. They can reach the surface without melting only if there’s little or no warm air between their formation region and ground level.

- If temperatures are just above freezing at the surface, then you may get snow mixed with rain (again, this is what they call sleet in the United Kingdom).

- If a warm layer is sandwiched between colder air above and below, then snowflakes may partially melt only to refreeze before they reach the surface. This leads to small, translucent ice pellets (or what we call sleet in the United States).

- If the warm layer is either deep enough or warm enough, the melted snowflakes may not have time to refreeze before they enter the cold surface air and hit ground. The typical result is freezing rain.

- If there’s a deep layer of warm air near the surface, then all of the snow will typically melt and reach the ground as rain.

Sometimes a winter storm includes a layer of supercooled water droplets aloft. Such a droplet lacks a tiny nucleus on which to freeze, so it can remain unfrozen despite temperatures below freezing. These supercooled droplets may cling to a descending snowflake and form a squishy coating of what’s known as rime ice. The result at the surface is snow pellets or graupel (pronounced “gropple”), which is typically less dense than ice pellets. (Snow pellets are also called soft hail or tapioca snow, as discussed in the AMS Glossary entry.)

Snow pellets can bounce and disintegrate like tiny Styrofoam balls when they hit the ground. Ice pellets are firmer, behaving more like small hailstones and making noise when they hit roofs or pavement.

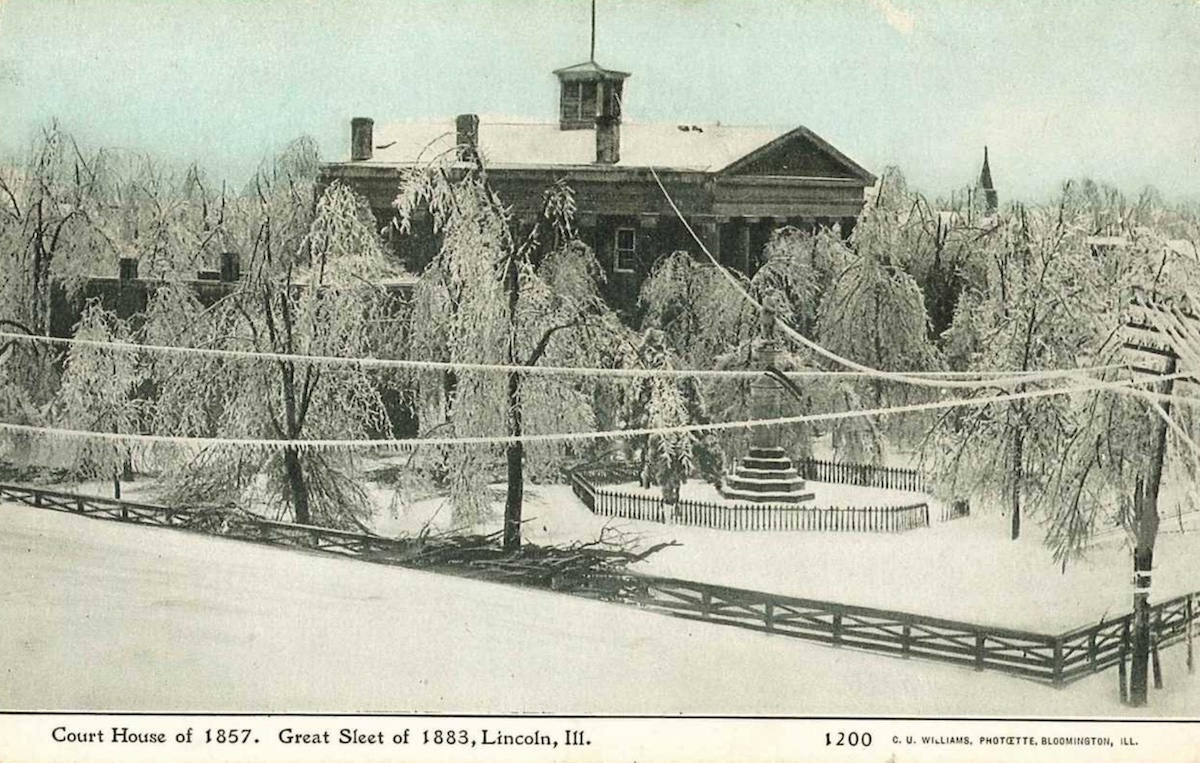

Shown above is an example that touches on most of these modes. A prolonged period of winter weather in central Illinois in early February 1883 transitioned from snow to “a kind of hard-balled snow” (perhaps graupel), followed by “fine, dry sleet” and then sleet mixed with freezing rain. The result was what we might now call an ice storm on the heels of a “wintry mix”, but people at the time dubbed it the Great Sleet of 1883. (Photo courtesy NWS/Lincoln, IL)

Winter precipitation adds to the fun (i.e., the workload!) of the thousands of volunteers in the NOAA/NWS COOP (Cooperative Observing Program) and CoCoRaHS (the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail, and Snow Network). These intrepid souls, some of them volunteering for decades, record not only how much precipitation has fallen each day, but also what type it was. The most diligent observers make note of when the precipitation changed from type to type.

Reports from COOP and CoCoRaHS are an irreplaceable archive that allows researchers and historians to reconstruct in detail how a winter storm unfolded from place to place and day to day. They’re even used by forensic meteorologists trying to deduce, for example, how weather conditions may have contributed to a slip-and-fall incident at the heart of a lawsuit. In cases like this, it can be crucial to distinguish among freezing rain, snow, and ice pellets.

Even if a “winter storm is a winter storm is a winter storm”, distinctions can matter!