When a Forecaster Issues a Tornado Emergency: Insights from the Front Lines

- By Ashton Robinson Cook and Bob Henson

- Apr 29, 2024

Destruction was widespread in Rolling Fork, Mississippi, after the high-end EF4 tornado of March 24, 2023, that prompted the National Weather Service Forecast Office in Jackson, Mississippi, to issue a tornado emergency. This photo was taken on April 12, 2023. Image Credit: Lance Cheung/USDA via Wikimedia Commons.

The word “emergency” seems tailor-made for a serious tornado threat. It’s a hazard that can materialize in just minutes, and if you’re just downstream, you may have only a few minutes, or even seconds, to react. A tornado emergency typically runs its course in less than an hour, but during that window, hundreds of homes may be destroyed and dozens of people could die. On Friday, April 26, two destructive tornadoes—one that moved through the northwestern suburbs of Omaha, Nebraska, and one in western Iowa that struck the town of Minden—were warned as tornado emergencies.

It was 25 years ago when the first-ever tornado to receive the “tornado emergency” distinction tore across central Oklahoma, including the city of Moore, on May 3, 1999. That tornado was so obviously high-end, and so close to a large metropolitan area, that forecasters decided to invoke “emergency” to convey a sense of the unusually serious peril.

The Bridge Creek-Moore tornado was indeed an outlier. It was rated F5 on the original Fujita tornado scale (equivalent to EF5 on the current enhanced scale), putting it among the strongest tornadoes in Oklahoma history. Along its 38-mile-long path, the tornado caused 36 direct fatalities, injured nearly 600 people, and became the nation’s first tornado to produce $1 billion in damage (roughly $1.9 billion in today’s dollars).

Interestingly, central Oklahoma was under only a slight risk of severe weather early on the morning of May 3. As described in a 2000 paper by NWS Storm Prediction Center forecasters Rich Thompson and Roger Edwards, there were “several difficult forecast problems” that day. Widespread cirrus was expected to interfere with heating, and there was uncertainty about whether enough upper-level forcing would arrive. However, by early afternoon, a now-defunct network of wind profilers detected a pocket of enhanced upper-level winds in New Mexico heading for Oklahoma, and a break in the cirrus soon allowed the day’s first supercell to form. The threat area was ramped up to moderate risk by late morning, and then to high risk by mid-afternoon.

By evening, a major tornado outbreak was in progress. David Andra, now retired, was the science and operations officer at the NWS Norman office on May 3, 1999. He recalled in a 2004 NOAA newsletter article: “At one point we used the phrase 'Tornado Emergency' to paint the picture that a rare and deadly tornado was imminent in the metro area. We hoped that such dire phrases would prompt action from anyone that still had any questions about what was about to happen."

Over the following years, the tornado-emergency wording was used elsewhere around the country on occasion, with specific criteria introduced at some NWS offices but no nationwide policy. It wasn’t until 2016 that “tornado emergency” was codified by NWS, defined as meaning that “a severe threat to human life exists and catastrophic damage is imminent or occurring.”

What is it like for a forecaster in Tornado Alley – or Dixie Alley – when a tornado emergency looms? Below are some thoughts from Chad Entremont, Science and Operations Officer at the NWS Forecast Office (NWSFO) in Jackson, Mississippi. On March 24, 2023, Entremont’s office was confronted with the year’s most destructive and deadly U.S. tornado, which ended up taking 14 lives in the devastated town of Rolling Fork. Entremont was on the team that issued the tornado emergency that evening along with many others issued by NWSFO Jackson MS. He’s also surveyed tornadoes in the area dating back to 1999.

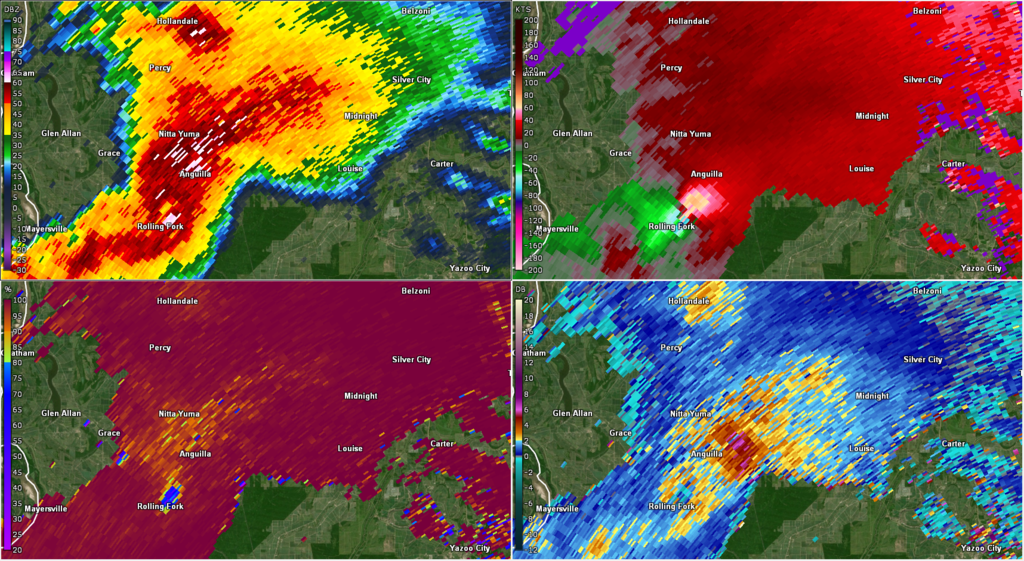

Figure 1: Intense supercell that spawned the Rolling Fork tornado. Image Credit: NOAA (KDGX Radar)

Figure 2: A home that was completely destroyed by the Rolling Fork tornado at EF4 intensity. Image credit: NOAA

What is a tornado emergency and how has it changed since first being issued in 1999?

The tornado emergency is the platform to ‘scream’ the loudest. It foreshadows and messages the worst of the worst kind of situation that we see. It is typically reserved for EF4-EF5 type tornadoes, although emergencies can be appropriate for higher-end EF3 tornadoes given their potential for substantial impacts.

We (WFO Jackson, MS) put procedures in place to issue tornado emergencies as needed in the early 2000s, not many years after the May 3, 1999 tornado outbreak. We went through a drought in violent tornadoes in our county warning area between late 2001 and early 2010, however.

Not all offices issued/participated in tornado emergencies initially and in the first few years of potential issuance. Emergencies became codified along with impact-based warnings and storm-based polygons as official National Weather Service policy back in the mid-2010s, enabling three separate tiers of tornado warnings (the worst including ‘catastrophic’ wording directly tied to the emergency) that all forecast offices were encouraged to issue as appropriate. Emergencies are rare, and some forecasters don’t issue one in their entire career. Example tornado emergency issued on March 24, 2023 for Rolling Fork, MS with catastrophic tag.

Advancements: Since our drought ended, we’ve issued several tornado emergencies including Yazoo City (2010); the Super Outbreak in April 2011; Louisville, MS (2014); and Rolling Fork (2023). Many advancements in our understanding of the mesoscale, near-storm environment have occurred since that initial tornado emergency, and we have a better idea of what types of impacts could occur as a result. We also have finer-scale, dual-polarization radar data with higher temporal resolution (i.e., SAILS scans) to more quickly and efficiently assess changes in thunderstorm structure. There’s also more chasers and real-time observers in the field that report to us and assist us in warning decisions.

Despite the advancements we’ve seen, challenges remain that include:

- Messaging: Ensuring the correct message is included in the warning (i.e., considerable or catastrophic tags) based on the data we have available in the warning environment.

- Getting people to take appropriate actions: We want people to respond to all tornado warnings regardless of tag, and not ignore warnings if they aren’t emergencies. Also, some people don’t get the warnings we issue. And even when they do, we’ve also observed situations where people got ample warning but had nowhere to go for safety. Those are heartbreaking cases.

Figure 4. A large home destroyed by the long-track EF4 tornado on April 28, 2014. Image credit: NWS WFO Jackson, MS.

How does decision making in a tornado emergency situation work? What was different about the tornado emergency in Rolling Fork?

The decision to issue a tornado emergency isn’t made in isolation. In our case, we deliberated internally in real time utilizing all available data to make the decision. We also have simplified flow charts to enable us to quickly make warning decisions based on the data we have available.

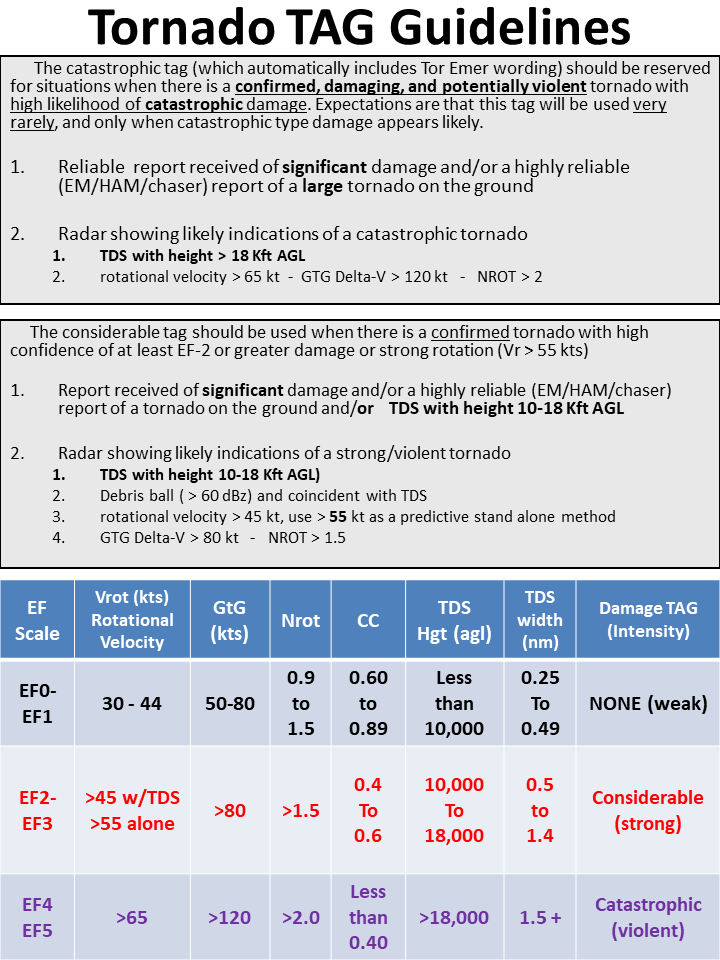

Figure 5: Tornado "Tag" guidelines utilized by WFO Jackson, MS in their warning operations. Entremont mentioned that population is not a factor for tornado emergencies in their county warning area because many residents live in rural areas.

I guess you could say for the initial severe to the tornado warning, the evolution was very rapid – much faster than what we’ve seen in other tornado emergency situations. The parent cell that produced the tornado was struggling and marginally severe back in Louisiana, but organized rapidly in just a matter of minutes. We issued a ‘considerable’ tag before the tornado was confirmed. We did that as kind of a forecast to get that next-level wording out that if a tornado developed, it would likely be significant given the favorable environment it was in.

In the radar scan right before the TDS (tornado debris signature) showed up, the trend in the rotation and just the structure was increasing and starting to meet criteria we have internally that suggested we could issue an emergency. Then chasers reported a tornado shortly thereafter. We also understood that the area west of Rolling Fork was rural, with not much to impact up until the town was eventually hit. The combination of radar data, chaser visuals, and [the storm’s] approach on the town of Rolling Fork led to the issuance of the emergency. We had to issue it quickly to get the critical messaging out to those in the path. ArcGIS Story Maps article on the Rolling Fork-Silver City tornado

What does a warning forecaster experience when issuing a tornado emergency? Is it stressful? Difficult?

We often see more excitement with newer forecasters and across social media when products like these are issued. But for us it’s rough. It’s heartbreaking. It takes a mental toll. We’ve seen these types of radar signatures before, and often we’ve performed official surveys of the catastrophic damage they leave behind. We know what’s happening in real time and we know that people are being impacted.

What improvements are needed to assist warning forecasters in the future?

The greatest challenge is with areas of lesser low-level radar coverage (i.e., the gap areas). The tornado emergencies we’ve issued have been in fairly solid radar coverage since having (WSR-88D) especially since 2001. We didn’t issue any emergencies for the violent tornadoes that occurred in the Delta in November 2001. We started putting that option in place for our warning operations in 2003-2004. The further away you get from radar and get into gap areas, there’s less confidence. This is partially being addressed by the introduction of supplemental low-level radar scans from nearby regional radars (KMOB in Mobile, AL; KSHV in Shreveport, LA). The move of the Slidell, LA radar (KLIX) to Hammond, LA will also help. Lastly, the University of Louisiana in Monroe has had occasional radar data available and we’ve used it as justification for a considerable tag in a tornado warning before.