Weather Maps by Radio

- By Dr. B.M. Varney

- Jul 31, 2023

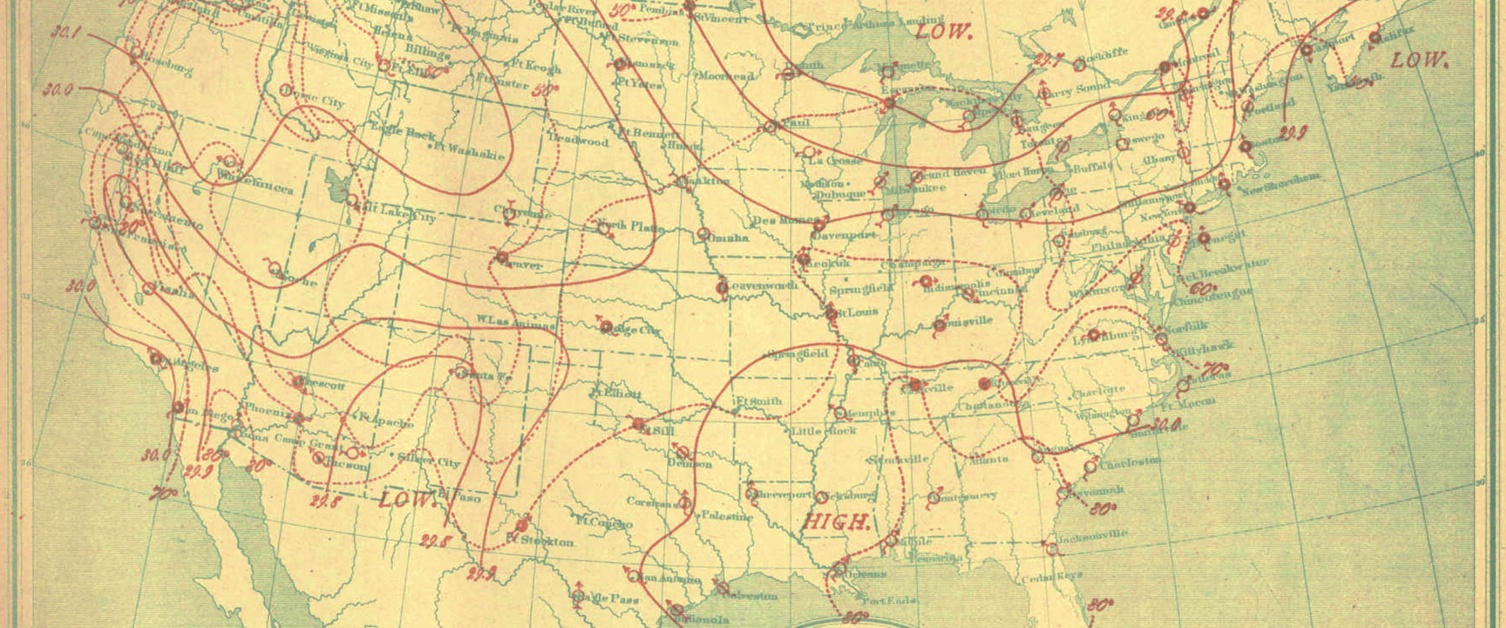

Caption: An example of early weather map before radio transmission. Source: U.S. Signal Corps, retrieved from the Government Information and Maps Library, University of South Carolina

Note: This is an historical account of the first radio transmission of a weather map. It was published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society in 1926.

In the photograph file of the U. S. Weather Bureau at Washington is an odd-appearing weather map, as big as an ordinary letter head, done in pale blue-green ink on white paper, and carefully preserved under a celluloid "glass." Someday this rather crude little map will possess great historic interest. If you examine it carefully you see that its every line is made up of many short lines, running parallel to each other and very close together, in the top-to-bottom direction on the paper. Across the bottom is written:

First experimental weather map transmitted from radio station at Arlington, Va., and received at Weather Bureau Office, Washington, D. C, on August 18, 1926. (Signed) E. B. CALVERT.

We have indeed come a long way since the first coded radio weather bulletin was sent out from the Weather Bureau via Station NAA. That was on July 13, 1913, 13 years ago.

The chain of events leading to the sending of this first radio weather map must be passed over very briefly. The inventor of the system which turns the trick is Mr. C. Francis Jenkins of Washington. Mr. Jenkins' work with "television" having come to the notice of the Weather Bureau, the question at once arose, "If pictures can be sent by radio, why cannot weather maps also?" Then followed conferences between the inventor and Weather Bureau Officials, which resulted in Mr. Jenkins developing an adaptation of his original television device to weather map reproduction, the securing of co-operation from the Navy Department for the use of the Arlington station, the preparation of a base adapted to the simplified weather map necessary for this work, and finally the initial broadcasting.

The scheme of operation is in outline as follows: The map for the day is drawn in the Forecast Division of the Weather Bureau, with black ink on thin white paper. A photographic negative is printed directly from this. The result is of course an opaque ground upon which the map shows as transparent lines. The negative is now taken to the radio station NAA, and there wrapped about a glass cylinder mounted horizontally as a part of the sending outfit. Close to the inner surface of the cylinder is a very small, powerful source of light. Exactly opposite this and close to the outside of the cylinder, is the tiny opening of a photo-electric cell. Both light source and cell are so mounted that a suitable worm gearing may drive them as a unit from one end of the cylinder to the other as the cylinder revolves.

We are now ready for the broadcasting. The negative map being on the cylinder, and the light source and cell at its left-hand end, the motor is started. A few revolutions of the cylinder serve to bring the first of the transparent lines between light and cell. Through this transparent line a flash from the constantly burning light so varies the resistance of the cell that it opens and closes an electric circuit. The circuit operates the radio emission of the first of the dots and dashes of which the received map is to be made. Thereafter until the map is complete, for every revolution of the cylinder the light source and the cell travel one-fiftieth of an inch to the right, and every time a transparent line passes between them a longer or shorter flash sends a longer or shorter dash, by radio to the receiver.

The receiver is much like the sender. Its cylinder is of wood, wrapped with a sheet of plain white paper, and in place of the travelling light and cell is a pen which moves in unison with them, and taps each mark upon the paper, under magnetic control operated by the incoming radio impulses. The clicking of the receiver and the irregular dots and dashes, sound and appear much like a badly jumbled code message.

Securing of adequate synchronism between sender and receiver constitutes one of the major problems of the transmission. Unless such synchronism is maintained the weather map becomes an unintelligible tangle. Since it is impracticable to make the two cylinders revolve at equal and constant speeds, a device is introduced which stops the receiving cylinder at the end of each revolution, and holds it through the varying number of hundredths of a second necessary to enable it to start the next revolution in step with the sending outfit. The very slight distortion of the map toward the bottom, resulting from lack of synchronism, is thus corrected.

Progress in developing this system of weather map transmission has reached the point where it is now a question of further mechanical refinements to improve the quality of the map, to reduce the time of transmission from the present fifty minutes to much less, and possibly to simplify the construction and thus reduce the cost of the outfit.

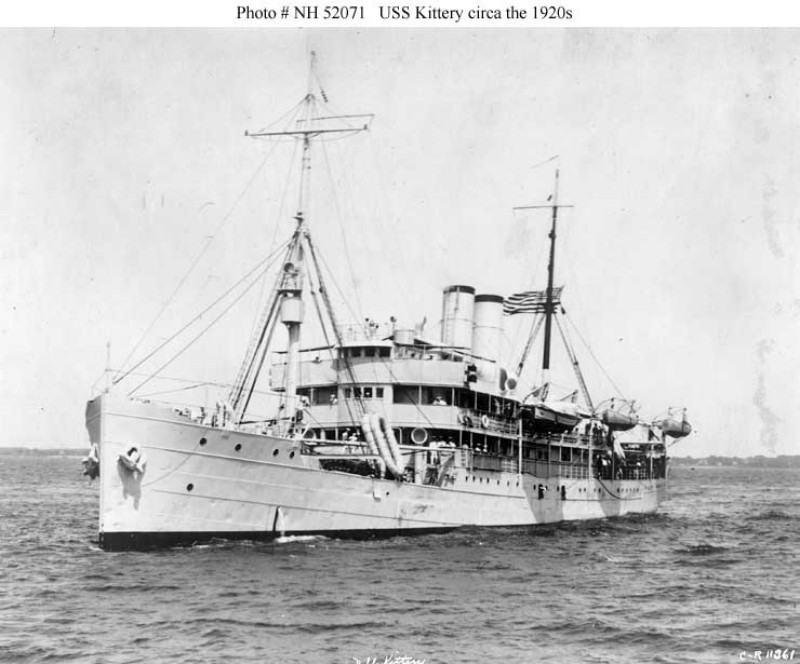

Source: U.S. Navy

The Navy, with its usual fine spirit, has been co-operating with the Weather Bureau in the tests. It loans the service of Station NAA each day for the transmission of the current map. It has placed receiving sets on board U. S. S. Kittery and U. S. S. Trenton, and the Kittery has received the map as far away as Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Reception has been accomplished in a thunderstorm, through rather bad static, the map coming through in very fair condition. The rolling of ships, and static, seem to be the greatest obstacles to be overcome. Distance tests are being carried out between Arlington and Chicago. Success in this direction as in the others, warrants the hope that radio weather maps will presently become feasible for more general use.

The system in use here is not without a rival. Some weeks ago, it was announced that regular radio broadcasting of a weather map from Munich, Bavaria, had already been begun. The European plan embodies an ingenious application of electricity directly to a sensitized paper for reproducing the map. The scheme is in essence this:

An original map is drawn in non-conducting ink on a conducting sheet of metal, which is then mounted on the revolving cylinder, as in the Jenkins system. Upon this sheet rests a very fine stylus which as each non-conducting ink line passes under it, opens a circuit that attends to the sending of the radio impulses. On the receiving cylinder is a sheet of paper sensitized to the action of electric currents in such a manner that each dot or dash registered upon it by a stylus is faithfully reproduced when the paper is "developed" by some suitable process. It appears thus that the "photographic" stage (there is of course no real photography about it) comes at the end of the whole train of map-making operations—at each receiving station, in other words. What the advantage or disadvantage is, in point of total time consumed in disseminating the map, we do not know as yet. The time used in the actual transmission is reported as being only about five minutes.